Twenty years on from winning the Landfall Essay Competition in 2004, ‘Race you there’ still cuts to the quick as a personal address to racial and te Tiriti politics in Aotearoa. Tze Ming Mok catapults us from Mount Roskill in the 1980s to Pōneke in the mid-2000s — to the front lines of a National Front rally and ‘the very end of the hikoi against the foreshore and seabed legislation.’ We are honoured to be republishing ‘Race you there’, accompanied by a new postscript by Tze Ming.

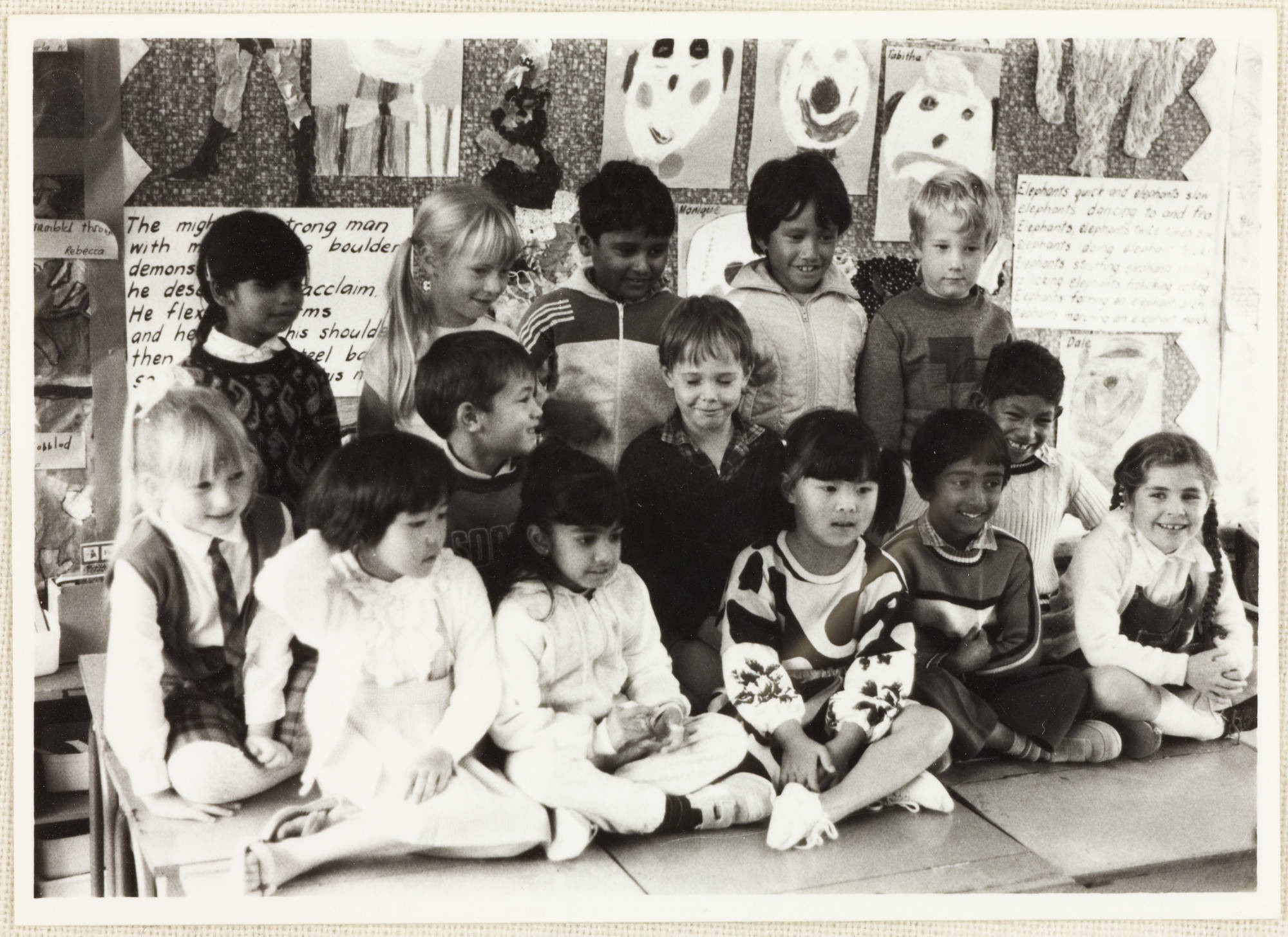

'Pukekohe Hill School is noted for the variety of nationalities that attend. They include-Canadian, Japanese, Indian, Maori, Dutch, Sri Lankan, German, English, part Samoan, part Tongan and of course, Kiwis.', excerpt and photograph first published in Pukekohe: 75 Years, 1912-1987, 1987. Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections Footprints (07979)

1. Face the future

The day will come when I won’t be a minority in this country. No one will be. This will be a shock to some people, to find that something can rise from the ashes of majorities and minorities. They’re called pluralities, it’s merely math.

When that day comes, I’ll find myself back in standard two. Hay Park Primary in Roskill South was, in 1986, an ethnic microcosm of the projected population of New Zealand come 2051.1 Well, maybe with more Samoans. That year, Madonna released True Blue, the white population of my class photo slid under 50 percent, and a multicultural future was born. Two years later, my standard four class was perhaps New Zealand in the twenty-second century: Polynesian, Māori, Asian and White, split roughly four ways. And the Somalis hadn’t even arrived yet.

Hay Park Primary sat on the divide between the “good side” of the rugby field and the state housing area. They called it a “white-flight” school. There was poverty; it was no dewy-eyed utopia — but there was something comforting and very stable about the balance of differences. It was probably the happiest time of my life. This was partly because words didn’t mean anything yet. Though we were ahead of our time, we were in the bubble of childhood. Hurts inflicted didn’t last, as though we weren’t able to remember pain. We didn’t understand what we were saying, or who we were, in what system. We didn’t even know the world was white. Unbelievable maybe, but true. I thought America was run by the Huxtables.2

The teachers approved of my triumvirate of friends because together we were a successful, popular epitome of Mt Roskill’s laissez-faire brand of multiculturalism: Samoan afakasi, Chinese, and Pākehā with putative streaks of Māori. ‘I’m a half-caste,’ Etevise once pronounced proudly; ‘I’m a quarter-caste,’ Kristy chimed in — she half-knew her quarter-whakapapa; ‘I’m a full-caste,’ I hazarded. ‘You can’t be a “full-caste”, “caste” means you have to be part something,’ Etevise declared knowledgeably. It was cool to be part something, because it meant you were part of something. White was not yet ‘something’ — none of us had read Being Pakeha at that point.3 What the hell were we talking about? It was just something to play with and toss around. Across the fence at Waikowhai Intermediate, my brother captained the Coloured Team in a Whites versus Coloureds soccer match, and gave those whiteys a thrashing, you know, metaphorically, on the field. Sometimes they’d call him Rice Risotto, which is of course Italian. This was probably why he was so good at soccer.

Anger, fear, the diminution of our place in the world, our affirmation of identities through negation of others … we awoke to all these things, the infrastructures of a system we had only been dimly aware of in our mouthings of interesting new words like “chingchong”, “currymuncher”, “boonga”, “hori” and “honky”. It came upon us all. Gradually. This was how you grew up. Each group drifted away from the others, under the shadow of knowledge. Now we have to figure out how to return to each other without becoming ignorant again.

I’ve always thought of Mt Roskill as the gateway to the world — you see, one has to drive through it to get to the airport. On your way south into this so-called world, you’ll speed towards a sign, welcoming you to Manukau: ‘Face of the Future’. It’s looking at you, kid. But you might have to face yourself first.

2. Marriages of convenience

Here is a phrase that is often in the back of my mind: as Tonto said to the Lone Ranger, ‘Whaddaya mean “we”?’4 I want to directly address my own people, and this is a tricky venture, for who the hell are “we”? Where am I going to find “us”? Will “we” really be reading Landfall? But I have to try. I’m taking a breather from trying to convince white people of anything. I’ve been talking to white people all my life — they’re everywhere. Every piece of discourse seems directed towards the Pākehā majority. But no one seems to ever address the Asian communities in a public, political sense, unless they want money — or unless we are addressing ourselves. There is a new system of politics emerging, and somebody has to ask: Are we together on this? Are you with me? Try this simple test:

When the anonymous skinhead punched Chi Phung in the chest and ran, Phung, a tiny, pigtailed Vietnamese student of sociology, lay crumpled and crying on a Christchurch sidewalk for twenty minutes. And as this now-ubiquitous anecdote of national embarrassment concludes: nobody came to her aid. Because of this, though I’ve slipped unnoticed through near-rioting Southeast Asian streets, and passed unscathed though China, Central Asia and the Middle East, there are parts of this country where the promise of my passport’s protection isn’t enough to put me at ease. Is it the same for you? If so, then for the next few pages, you are my people.

Malti Gurung, Christchurch Botanic Gardens, 1990. From a collection of photographs taken by Gurung after arriving in Christchurch from Nepal. Canterbury Stories (CC-BY-NC-SA 4.0)

I have been to Christchurch only once. I was seven or eight years old, and remember cool, crisp air, a pearly rose garden, and an old lady peering at me from her car window, asking me for the first time in my life: ‘Where are you from?’ I panicked on the sidewalk, wobbly with a feeling of being lost at sea, and hazarded a guess in flat kiwi tones: ‘Nyi Zilln?’ My mother laughed, to cover up someone’s embarrassment, but whose, I still don’t know. ‘No Ming, that’s not what the nice lady means.’ And turning to the nice lady, smiling brightly, she said in her sing-song Singapore accent: ‘We're from Auckland.’

More recent events in Christchurch have been cause for both hope and despair. The attack on Phung sparked Christchurch’s first serious immigrant-led anti-racist movement, culminating in a 2000-strong street march, which dwarfed a rival turnout of barely two dozen National Front members. Asian and migrant communities could be forming a nascent political sector if not an actual political force. It’s been a long time coming. But rather than self-congratulation, this development should summon an urgent self-examination of our place in this roiling grumble that is passing for a race relations debate.

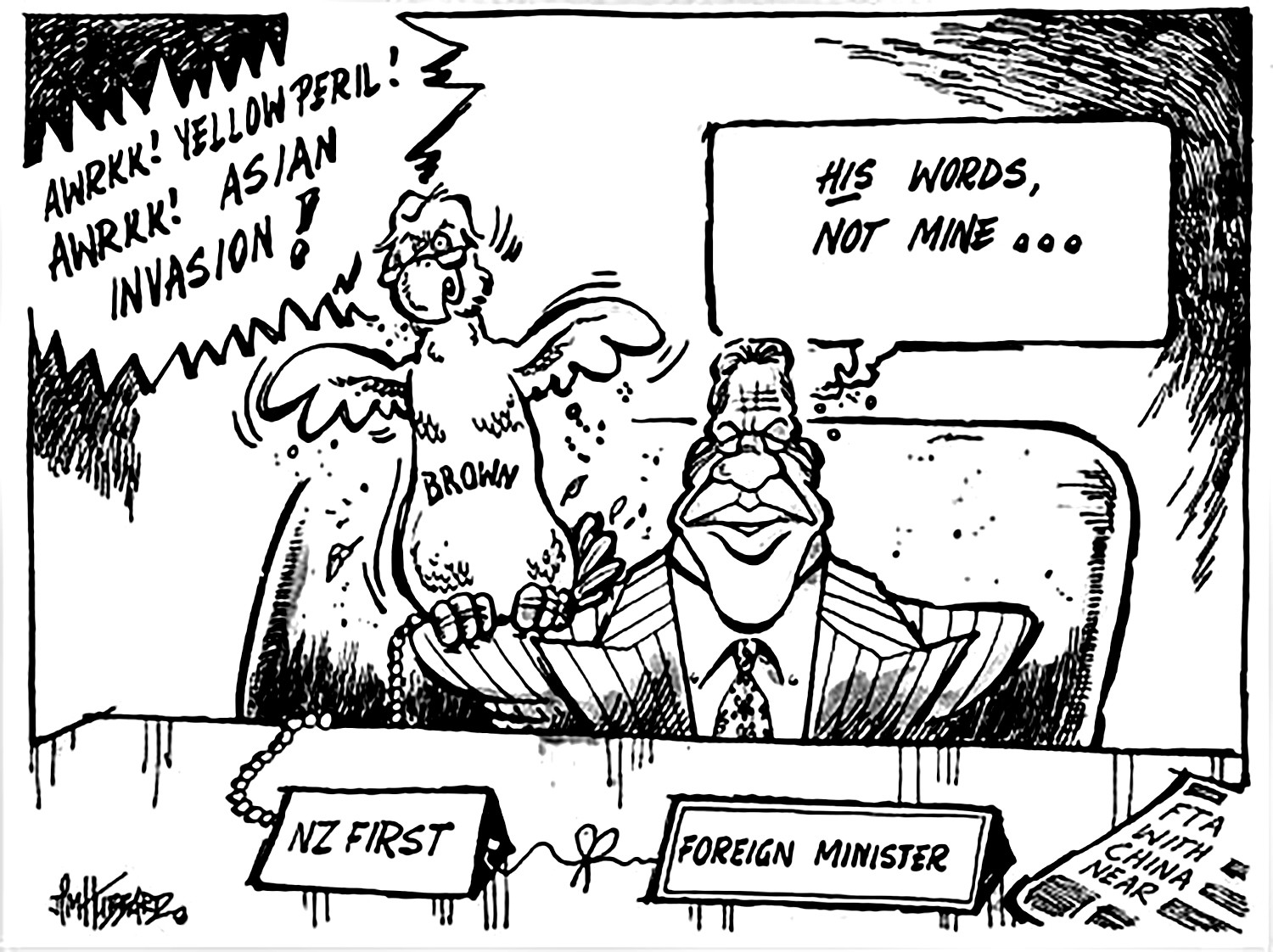

Merely being non-white is no guarantee of being non-racist. Being married to a non-white person has even less bearing on how racist you might be. And there is raging miscegenation amid the leaders of the right. When Don Brash breaks into his constant refrain, ‘I can’t be racist — my wife’s Singaporean’, one can only assume he is referring with the utmost irony to the fact that Singapore has had an avowed state eugenics policy since the 1960s.5 The only positive inference for race relations that can be awarded to Dr Brash based upon the nationality of his wife, comes from the fact that she has left Singapore. Bill English’s adoring Mary is Samoan afakasi; Richard Prebble’s wife is a Solomon Islander. Both erstwhile party heads have paraded their Pacific connections while trying to marshal what can only be characterised as the anti-Māori vote. Brash’s intention to replace the Ministry of Māori Affairs with a far more “relevant” (and presumably “less racist”) Ministry of Asian Affairs is yet another sign that multiculturalism is about to come of age. For as the non-white hordes increase and diversify, any tradition of a unified struggle for dignity has morphed into the horse trading of divide-and-rule politics.

Merely being non-white is no guarantee of being non-racist. Being married to a non-white person has even less bearing on how racist you might be.

People of recent migrant background know that sectarian deals, sweeteners and coalitions, are part of the normal functioning of multi-ethnic countries. You want to run a country without special acknowledgement of ethnicity or religion? With no acknowledgement of group rights? No way, it’d never work. Not in China, India, South Africa, or even … Singapore. Do you want a riot on your hands? When we’re from places like this, it should be easy to recognise that when the rhetoric of race-blind neutrality is used to take away the rights of an already disadvantaged group, or to derogate from treaties with indigenous people, that the dominant group is asserting its dominance while pretending not to. To disregard race? To be colour-blind? It may be the liberal dream, but it is not the democratic reality. For the state to be “colour-blind” while trying to preside fairly over multi-ethnic societies is just plain blindness.

The Asian banking unit at the National Bank of New Zealand in Auckland, date unknown. Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand

It is barely necessary to point out the cynicism of “colour-blind” rhetoric from the right, when they are drawing lines around groups that exist (we do, undeniably exist), pinning them here, counting them there, stacking up the numbers, and playing them off against each other. We Asians are dubbed by our Western WASP host societies as “model minorities”, the group most likely to be courted by the power elite to be used as a shield against accusations of racism. Not all Asians are married to Brash, but I bet he wishes we were. So hard-working, meritocratic and capitalist — boy would we keep the house clean. Even better, many Asian groups have a reputation for being uncomplaining and apolitical. And for good reason — the well-travelled Chinese and Indian global diasporas know that to kick up a fuss gets you kicked off the bus.

There are exceptions. We can’t help but get a bit touchy after being beaten up.

Dylan Owen, National Front demonstrations at Parliament Grounds, Wellington, October 23, 2004. Alexander Turnbull Library PADL-000074

3. What are you afraid of?

Lately, I feel as though I’ve been spoiling for a fight. Maybe that’s why I turned up to a National Front rally on June 9th this year, outside the Chinese Embassy in Wellington. I was the only Asian there. Being from Auckland it was my first encounter with real skinheads, and I would have been more afraid if I hadn’t been so curious. They had travelled here from around the country, but even so, their numbers peaked at about fifteen, and they were tied up insulting a clutch of young lefties that had turned up to insult them. The anti-racist kids formed an ad hoc counter-demo, small by the usual standards, but one that easily doubled or tripled the National Front’s turnout. The skinheads were demonstrating against a free-trade agreement with China, on the basis that it gave jobs to inferior races. I strode up to the front, threw out a sarcastic challenge, waited for the abuse.

‘You’re a peasant,’ spat a ringleader with (of course) no hair.

‘I’m a peasant?’

‘Go back to your third-world country.'

‘Is that the best you can do? Come on man! Bring it on!’

Perhaps I had briefly succumbed to insanity. He had murder in his eyes. But then he turned away from me, hefting his New Zealand flag like a spear over his bulging shoulder. And that was it. My persistent presence threw them. They didn’t know what to say to me. I would eyeball them, they’d look away. The only explanation the head Nazi gave was that the sight of me revolted them so much, they couldn’t look at me. They couldn’t face the future. Only take a bash at it, and run away.

The police officer in charge of keeping the peace was grandly and repeatedly misquoting Voltaire, while refusing to tell me whether any of the National Front members were from around here. I needed to know whether I was taking my life into my hands. I was chilled by the ice over the phrase ‘defend to the death’.6 ‘Don't be afraid,’ I was finally instructed by another police officer.

That cop was right. We don’t need to be afraid of this scant handful of unhappy boys who mostly just need therapy and to join a trade union. They were such confused young men that they couldn’t even work up a good racial slur against a girl so gratuitously chinky that her handbag had a panda on it for chrissakes. One skinhead looked so lost that I tried to perform a little slow-moving qi gong on him, to open him up, and transmute his angry energy and mine, into benevolence. Simply put, qi gong is the Chinese version of yogic meditation or Japanese reiki. ‘Hey, I’ve seen this on Dragonball Z,’ someone said, and then they fell silent as I pushed qi into his chest. The kid was afraid. He didn’t know that I was opened up too, trying to establish a channel, trying to help him.

Media coverage of the Christchurch march took pains to mock and deride the National Front members present. But it’s all too easy to displace latent racist attitudes onto the figures of deranged Nazi thugs, and also easy to misdirect our fears. One of my friends preparing for a work trip to Christchurch has literally had nightmares about the National Front. But there were hundreds of ordinary people with full heads of hair present that day on the street when Chi Phung was beaten to the ground. They did nothing. They are the real nightmare.

By now Christchurch, the city itself, has taken on the scapegoat personality of the country’s worst instincts. And this will allow the rest of New Zealand to just walk blankly on, stepping over the fallen on the sidewalk.

4. What are you made of?

Perhaps I am being uncharitable. Maybe Phung was so small that she could not be seen by the naked eye. Perhaps she briefly turned invisible. It is possible. Migrants and their children are magical people.7 We have the power of flight, the power of shrinking, and of invisibility too. In the past it’s been what saved us. We have flown, fitted in to small spaces granted us, and blended into the background. Many Asians, and people from refugee backgrounds, have roots in countries where they have been vulnerable minorities, sometimes with protection, sometimes without. Finding that protection in New Zealand has historically been a matter of assimilating into a culture that is unquestionably white, not into some impossible idea of a “colour-blind” nation free of ethnicity. But times have changed, and I’m grateful. I’m not Old Generation Chinese, nor entirely new — I’ve never begrudged the new migrants their right to be unapologetic in their ethnic identity and their difference. In fact, I’ve welcomed their presence for allowing me to be unapologetic. They’ve drawn attention towards us, towards an idea of “us”, after so many years of our hiding and forgetting who we are.

In New Zealand, the “Asian” label has yet to become a strong collective identifier that unites our diverse groups from within, except in times of strife. It’s when we have been attacked that we have responded “as” Asian. Each time this has happened we’ve suddenly found our communities speaking to each other and interacting for the first time in a new political and cultural space — speaking to ourselves as though looking into a mirror and seeing another room stretch out before our eyes. We can take inspiration from the consolidation of the Pacific peoples’ voice, although the Asian demographic’s spread of cultures and socioeconomic status seems far wider. How long can this space hold out without collapsing?

The Christchurch marchers spanned the breadth of the immigrant and ethnic minority communities. As a television journalist kept repeating, this was apparently the birth of ‘a new kind of migrant’, a migrant who presumably didn’t take any crap.8 To help the viewer’s imagination along, some footage was inserted of “rioting Asian youths” in Bristol, perhaps to let those skinheads know what we’re made of. (Why didn’t they just splice in some Bruce Lee?) That footage may have been a little confusing for those who don’t know that in the UK, to be “Asian” is to be “politically black”, as Hanif Kureishi once wrote with a smirk.9

To identify as “Asian” in Britain is to subscribe to a relatively unified pan-ethnic identity as South Asian or Indo-Asian, that is, from the diasporas of India, Pakistan, Bangladesh and Sri Lanka. Not only are British Asians generally black, they may also often identify as both black and Muslim, or even black, Muslim and working class. In the mouths of non-Asians in New Zealand, the word “Asian” doesn't tend to mean black or Muslim, and certainly not working class — even though all these groups are well represented in New Zealand’s Asian population, and even though professional East-Asian migrants often end up working at Pak‘nSave.

This kind of narrow categorisation makes the desirable, less controversial, paler, richer sections of the “Asian” demographic ripe for splitting off in the divide-and-rule game. We even do it to ourselves. In 1998 I attended the Yellow Ribbon demonstration in Aotea Square. The rally was in support of the Indonesian Chinese shopkeepers of Jakarta, who were mercilessly looted and assaulted during the riotous fall of Suharto that month of May. It was memorable for its strong turnout, punctuality (of course), and the vociferous anti-Muslim rhetoric spouted by middle-aged Mandarin-speaking men. Enough of this was translated to an articulate Muslim Indian woman from the Shakti women’s centre for her to take the podium and make a pan-Asian appeal for solidarity against dictatorship and violence. The response was lukewarm, the Town Hall clock struck one-thirty, everyone dispersed. And that was our last stand for six full years.

It takes actual physical attacks to mobilise Asian communities into political action. But ‘stop hitting us please’, though difficult to argue with, doesn’t go very deep — we never manage to catch the roots. Opportunities to break down ideologies, to deepen connections between our communities and with other communities, are appearing like never before. To seize these opportunities requires acute self-awareness, and openness to those who are unfamiliar or hostile. It’s a moment of negotiation and vulnerability. No wonder we’re afraid.

James Hubbard, "AWRKK! Yellow peril! AWRKK! Asian invasion!" "His words, not mine...", April 8, 2008. Alexander Turnbull Library DCDL-0006298

5. Civil union

Phung boycotted the very march she took her fall for. Why? “Anti-racism” is not as black and white as it may seem. She felt there were some coalitions the march organisers were not willing to enter. Phung had placed her finger on a trigger-point. She believed that the root of white aggression against non-white immigrants and foreign students was premised on white Pākehā denial that they themselves are an immigrant people. For Phung, the key to asserting migrant rights to belong in New Zealand is for all newcomers to see their presence as an “entry by Treaty”. Once through that quasi-constitutional pledge of allegiance, as it were, to the Treaty of Waitangi’s principle of partnership between Māori and Pākehā, we will belong to this place, and no one will be able challenge our right to be here as sworn partners of the indigenous people. Blood brothers, Kemosabe.

Phung argued strongly for the only viable long-term response to racism in New Zealand as being a coalition between those of recent migrant origin and the tangata whenua. The march organisers tried to strike out over this canyon, acknowledging that the march against racism started ‘a long time before us’. On the day, Ngāi Tahu came forth to extend their support and already we were halfway there. A coalition strained to connect — but did we all make it across? The real solution in Phung’s message was lost, and needs to be rescued. Our high-profile migrant politicians exhibit no noticeable drive for political partnerships with Māori. But here on the ground, we can’t fool ourselves into thinking that we can dabble in horse trading when we are the horses.

People of South, East and Central Asia, of the Pacific, Africa, and the Middle East: we have to take on the reality of our legal (if not ethnic) role as “Pākehā” and reject the longstanding fallacy that the Treaty is ‘not our business’. The principles of the Treaty give us rules of engagement; if we accede to them, we will access our right to be different. Just imagine — you could assert your right to belong here based not on the length of time you’ve lived here, or the proximity of your homeland to New Zealand, or the turns of your accent, or the amount of money you’ve paid to the government, or the colour of your skin, but on your commitment to the place’s founding principles. I know it sounds crazy, but it just might work.

Māori got enough of a raw deal with the first round of newcomers: given this new era of political trade-offs, they may be understandably suspicious of a group being racked up by the opposing side. And among Asian communities, there is a manifest lack of interest in comparing Māori and Asian colonial experiences. On both sides there is a tendency towards basic class-divided, colour-barred racism, fed by ignorance. But we can’t afford another front. We can’t fight so many battles. We have to strike a new kind of deal.

Perhaps I am a Knock-Off, or a Parallel Import. At that time, the Old Generations began dissociating themselves from the New Wave, and plenty still do.

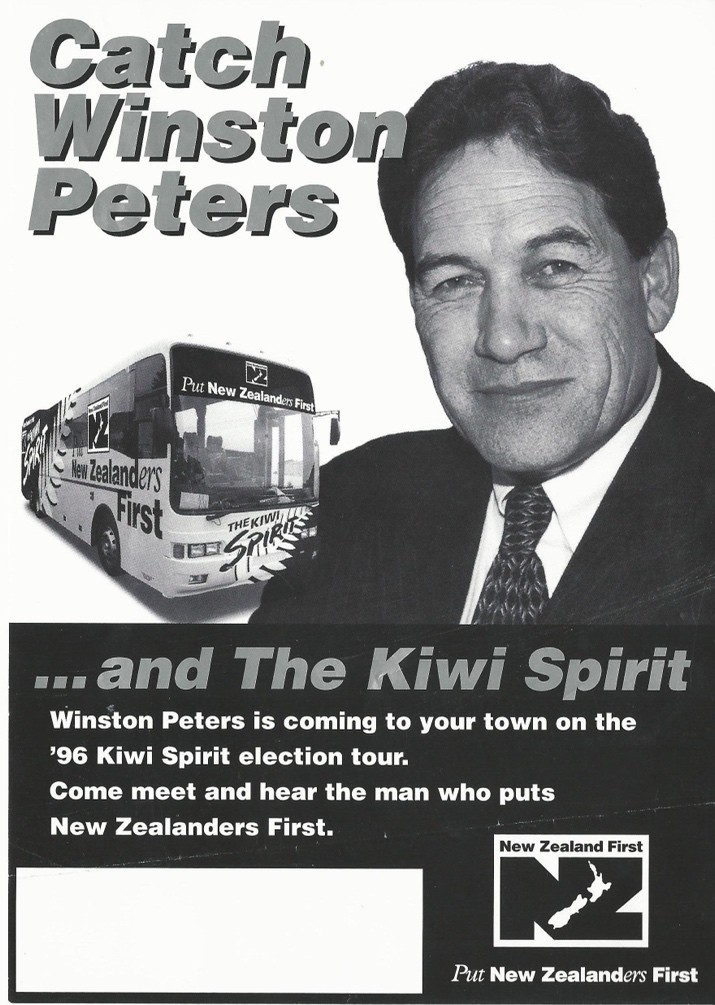

NZ First general election campaign flyer, 1996. New Zealand Election Ads

If we don’t, the low-level, gut-rumble of fear for our people may never stop. It comes and goes, particularly around election time. During the run-up to the 1996 election, I lived in an unalleviated state of fear and panic. I thought it would be a perfectly fine idea to take the suggestion of what appeared to be up to half of the country — to go the hell home. But there wasn’t anywhere to go but Mt Roskill. And they were burning crosses on Somali lawns there. One day, as I walked past Hay Park Primary, a throng of high-spirited schoolchildren followed me along the field’s perimeter, calling ‘do you speak English?’ over and over. These were just mocking play-words, meaningless to those kids. But not to me, not anymore. Perhaps it was a perfectly reasonable question, but I didn’t feel like answering. I went into the school and talked to the teachers, who remembered me, and found myself reduced to tears. They sat in a circle in the same old staffroom, looking smaller than they used to, lips pursed in concern, watching their finest work unravelling. They probably gave a little talk about it in assembly.

At that time, most of us were being regularly abused at a frequency we’d never before experienced. Plenty of us couldn’t come up with a showstopper like: ‘My family has been here since 1894!’10 Gilbert Wong, our most prominent Chinese journalist, has dubbed the Old Generation Chinese “The Originals”.11 Perhaps I am a Knock-Off, or a Parallel Import. At that time, the Old Generations began dissociating themselves from the New Wave, and plenty still do. I had previously thought that “dissociating” was a psychiatric disorder, or something people did during the Cultural Revolution to avoid being sent with their dissident friends to the labour camp. When it affects whole communities, it’s an illness symptomatic of a simple deficiency: that of having no allies.

In 96 Winston Peters had mopped up Māori support. A proposal was even floated that the Chinese, having driven the ancestors of the Polynesians out of Asia, were arriving again now to drive them out of Aotearoa. We were long-lost continental cousins, reunited at last, but none with any way out of this joint. During this period I met a proponent of this rhetoric at the Auckland University Marae. It was Dr Ranginui Walker, first in line for the hongi. I was so terrified of him that my flat Chinese nose skidded right off his pointy white-looking one, and squished into his left cheekbone. It was the most embarrassing moment of my life. ‘Where are you from?’ he asked wryly, probably in reference to my apparent inability to master this simple manoeuvre. ‘… Um,’ I squeaked, ‘Craccum magazine?’ It wasn't what he meant of course. He nodded politely as I burbled stupidly about my family background. What would he have said to a simple: ‘I’m on your side’?

Frances Waaka, Foreshore and Seabed hikoi arrives at Parliament, May 5, 2004. Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections N0111088 (CC-BY)

On the steps of parliament a few months ago, I leaned my umbrella over a Māori woman trying to light her rollie in the rain and got the same old question: ‘Where are you from?’ These days I’m quick to cover all the bases. ‘I’m-Chinese-I-was-born-in-Auckland-my-parents-are-from-Southeast-Asia.’ It’s even more complicated when people ask me what my name is. She genially told me that her ancestry was traced back to China too, though I’m not sure if she meant that she had some goldminers in the whakapapa, or if she meant “Chinese” in the Winston Peters sense. It didn’t matter; they were just words. We both knew where we were standing, which was next to each other, at the very end of the hikoi against the foreshore and seabed legislation.

I had watched that enormous mass of people flow down Courtenay Place without a gap for an hour before I spotted my friends — Māori and Pākehā — and stepped into the hikoi. Every time I’d seen another person of Asian descent amid the marchers, I became comically excited. All three times. Were there as many Asians on the 15,000-strong hikoi as there were National Front members who tried to stare down the Christchurch anti-racism march, or even as many as those who gathered outside the Chinese Embassy in Wellington? There was Hannah Ho: an anti-racism activist, Wellington-born Malaysian-Chinese and friend of Chi Phung. I was greeted in Cantonese by a middle-aged lady — who was she? The famous Nancy Kwok, one of the Old Generation, a former Communist cadre, and beloved of Ngati Poneke? Or Bic Runga’s mother? I had a photo taken with a Filipina lady who worked for the Refugee and Migrant Service. And there was me: Southeast Asian mish-mash from Mt Roskill. Maybe Asians who take the Treaty of Waitangi seriously are the lunatic fringe. But that day, amid the 15,000, there was no face we couldn’t look into.

How can we get to the end of fear? This is a still a safe place to grow up, and a free one. That’s why my parents came here. When we look at this place from our “outsider” perspectives, it seems like such a young country with such small problems. This opening phase of petty deals and self-protection is an adolescent, immature stage. Some of us remember race clashes, state pogroms or even genocides in our lifetimes, in our old countries. Here, I refuse to believe that rioters will ever come to tear down our shops, burn our sacred places, and drive us into the sea. The other path is wide open, and people too are still open. We don’t have to close ourselves off, even if we’re used to those kinds of defensive moves. It’s safe enough to take a gamble — to grow this country up, and grow into it. Whether of the New or Old Generations, we can’t afford to be among the passers-by, hidden amid the ranks of white society, hurrying past the darker, poorer minorities punched to the pavement. We need to realise that if Māori are expendable we are all expendable, and that the only lasting alliances will not be engineered by political parties, but by the people; not unions of convenience, but of love.

⁂

Editor's Note

This essay is republished as it was when first printed in 2004, aside from a few minor changes such as new images and the way footnotes are presented.