Nisha Madhan knows both sides of the artist–arts programmer divide intimately — the burning frustrations as well as the rewards of making work together. As her time as Next Wave’s lead creative producer draws to a close, she reflects on learning to listen.

Rapid Creek

Photo by Rhanjell Villanueva

I. NADINE

In August 2023 I was lucky enough to sit for some time by the mouth of the Rapid Creek river, on the land of Larrakia Country, with Nadine Lee, a deeply creative and hilarious Larrakia woman. I hold the image of her sitting on the grass — with the creek silently moving behind her, holding court with a small group of artists, sharing the stories, myths and legends that shape life for her and her family — firmly in my heart as I commit these words to paper.

I am an immigrant, a guest in so-called Australia. I have travelled through three different countries to arrive here. My ancestors come from the hills of the Himalayas and waters of the Yamuna River, which flows through the plains of Punjab. They were displaced through the partition of Pakistan and India in the aftermath of British Colonial rule and walked from that northern border, near Lahore, to my chaotic and complicated hometown, New Delhi, India. I was born, however, in Doha, Qatar, with the sound of the call to prayer etched in my bones. I lived between the mosques and sand dunes of the Middle East, and the hills and rivers of India until about thirty years ago when, due to political unrest, my family moved to the bush and flightless birds of Aotearoa New Zealand, where I became an independent artist.

I have a pretty volatile relationship with institutions. In the capitalist, colonial and patriarchal regime within which we live, they feel like walls built to keep people like me out. I don’t trust contracts, I don’t trust bureaucracy, I don’t trust organisations. To me these are a type of witchcraft, counter to my own, intended to bind me into spells not of my choosing. I don’t trust any of it and I’ve been known to have about a two-year attention span with any institution before I start trying to tear down the walls with my bare hands.

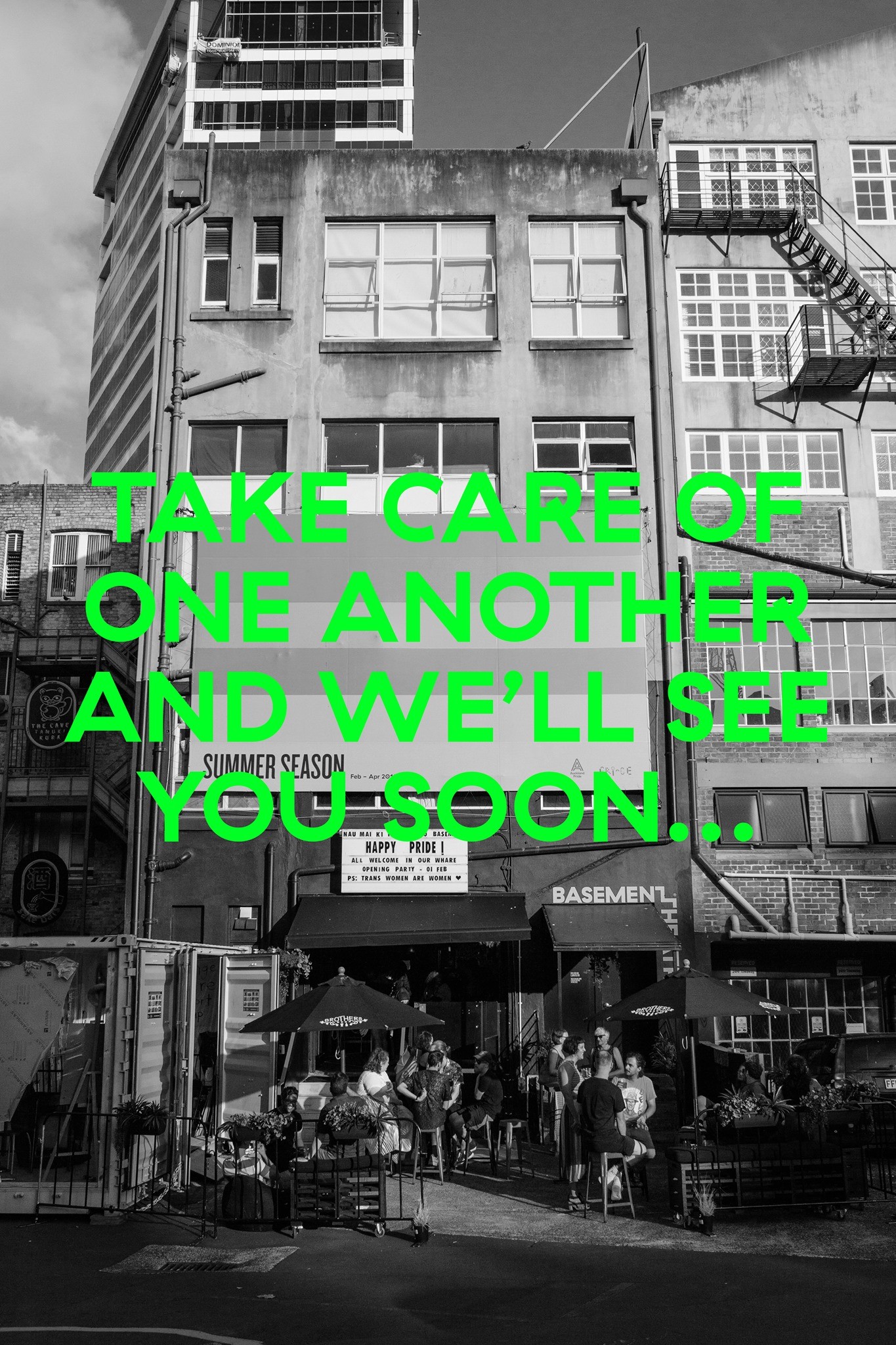

My first look-mum, no-hands real job was only a few years ago, as the programmer of Basement Theatre in Tāmaki Makaurau. On my first day I found a letter on my desk, left by my predecessor, Gabrielle Vincent, with the words ‘only open in an emergency’ on it, part of a longstanding tradition amongst the organisation’s programmers. Most people took years to open theirs, or only opened it once they had resigned, but within six months, I was crouching underneath my desk, opening the letter, as borders closed down due to the global Covid-19 pandemic. Gabrielle later told me that when she wrote it she never thought that I’d have to close the theatre indefinitely and transform myself from a programmer into a social worker as quickly as possible.

Basement Theatre's closure announcement during the COVID-19 pandemic, 2020

Basement Theatre

I worked hard during the pandemic to ensure the care and safety of the artists that inhabited our space, predominantly Queer and BIPOC. I worked so hard that I earned the title ‘aunty’ in my community, and I’m proud of that. This is where I began to understand myself as a curator who cares for people and cultivates relationships, rather than a shopper of art. From my point of view, if you really want to commit to practices of care, you need to be taught and schooled by artists. To be taught, you have to earn their trust. To be trusted, you have to be ready to fail. I’m known as a caring arts worker, not because I always got it right, but because I got it wrong several times and was schooled. I have come to consider artists’ trauma dumping, complaining or raging against me — a salaried arts worker — as an act of pure and unbridled generosity, a precious resource. The independent artist who raises hell when an organisation fails to attend to their needs is doing so for free, propping up our industry with hours of pro bono work. Those of us who are paid to be here should, at the very least, listen and honour their right to complaint. That is where care starts.

Remember when the pandemic hit and suddenly artists got access to a weekly income, topped up by Creative New Zealand, as well as 100% government-funded event insurance, free space, time and resources, and several high-trust funding schemes? To me these steps should be our baseline of care as we contend with a world on fire.

Caring for artists through a pandemic really shaped who I am as an artist, producer and curator. My experiences navigating government bureaucracy on behalf of Queer BIPOC artists, to make sure they had the financial support they were entitled to, taught me that care isn’t something you preach, it’s something you do. But after being a front-line responder to artists in need, and watching those great steps forward in artist care promptly be forgotten as the world bounced merrily back to its neoliberal rhythm, my own resources were severely depleted and I needed to leave.

The independent artist who raises hell when an organisation fails to attend to their needs is doing so for free, propping up our industry with hours of pro bono work.

I answered a call from Next Wave, a dearly beloved arts organisation based in the country of the Wurundjeri Woi Wurrung people of the Eastern Kulin Nation. Next Wave is known for its curatorial framework, co-built with eight artistic directors from across the continent, called ‘Curation as Care.’ Having completed my master’s portfolio ‘Islands of Hope and Care’, on the intersections between Queer BIPOC artists, experimental practice and care, Next Wave’s Curation As Care framework was stupidly aligned with my own framework for art and life. Next Wave pursues a decentralised model, with one artistic director in each state and territory across the continent, debunking the idea that one person is capable of the kind of community and care required for this role.

This is a new direction for Next Wave, which is still widely thought of as an annual festival for emerging experimental artists. In response to everything that happened in 2020 and under new leadership, the decision was made to dismantle the festival model and lean in to Next Wave’s strengths to nurture, care for and develop artists; and, rather than compete with other local and national festivals, to invest in partnerships, relationships and site-specific exchange and development.

It is hellishly complicated, super hard and not straightforward at all. Because decentralising power and centring artist care are, horrifically, new behaviours for our industry, there is no road map. We have to build that map in an industry that struggles to slow down enough to truly allow this work to happen, even after going through a global pandemic together. I admire an organisation that is willing to try, to fail, to listen and learn. This is what I believe will result in a sustainable future for arts organisations, walking hand in hand with artists.

It is hellishly complicated, super hard and not straightforward at all.

II. BIRDSONG

Whakarongo ake au ki te tangi a te manu nei

Tui, tui, tuituia

Tuia i runga, tuia i raro

Tuia i roto, tuia i waho

Tihei mauri ora!

I listen to the cry of the bird

Calling us to weave together

Binding that which is from above, with that below

Binding that which is from within, with that outwards

Behold the sneeze of life!

This Māori tauparapara was taught to me by Manawanui Mihaere and Mischellé Tohu, a reminder of the many dimensions to the act of listening.1

MarketMarket, presented by ACCOMPLICE and Next Wave, 2023

Photo by Migs Ellaga

Through a long and steady friendship built over many years with Britt Guy, who works under the moniker Accomplice, Next Wave invited five artists from around the continent to spend time in Larrakia Country, meeting, listening and witnessing the particular and deadly way that artists local to this area work. Hosted as part of the Darwin Festival, thirteen of us set up office in an empty shop at the Rapid Creek Markets. Amidst the hustle of the markets, there we were, a huddle of artists, treating our time, connection, dialogue, our right to complaint, our innate hope and visions of the future with the same amount of urgency as getting flat chilli noodles served to you in that small but perfect Sunday-morning window. We named this exchange MarketMarket in honour of the site, and this is how I found myself sitting beside Nadine, listening to her stories.

With Nadine beside us, we watched and listened to the birds of Larrakia, under the expert guidance of Dr Amanda Lilleyman, aka Dr Bird. We dined at long tables amongst exhibitions at Coconut Studios and the Northern Centre for Contemporary Art, we experienced the incredible gush of joy that was the Sangeet at the Darwin Festival, and we presented experimental works by Matthew van Roden and Carlo Ansaldo, Mikaela Lee, Kelly Beneforti and James Mangohig. All amid the market at night, while spotlighting three local vendors and their heritage cuisine. We even swam at Nightcliff Beach under watchful local eyes.

I’m not gonna lie, it was one hundred percent dreamy and there was not an outcome, deadline or KPI to be seen. I left with an exchange with Dr Bird ringing in my mind, almost like a curse she had bestowed on me: I asked her, “Once you start listening to the birds, can you switch it on and off or are you always hearing them?” She said, “No, I can’t turn it off or choose when to listen, and now that you’ve started listening you’ll never be able to turn it off, you’re fucked mate.”

As a guest, this is the way I love to meet a country. Through its artists and their conversations. It makes me ask: why bring in another conversation, sounds from somewhere else, when there is already so much birdsong to listen to here? Perhaps in time I might, but for now, I’m blessed and cursed with the need to listen to what’s here first.

MarketMarket DJ, Kuya James, presented by ACCOMPLICE and Next Wave, 2023

Photo by Paz Tassone

This careful programme was curated by Accomplice and my experience of care through their curation was passionate, thoughtful, detailed. It left me with a deep sense of what it means to choose to stay and invest in the rhythms, the seasons, the particular sway of life in Larrakia, rather than run to the supposed powers of big-city arts markets.

The process was not always a box of birds — there were hard conversations, the drawing and redrawing of boundaries, constant defining and redefining of shared values, and negotiations of trust. I had to reckon with the independent status of Accomplice, who were bringing their hard-won local knowledge and relationships to a programme without the financial security that Next Wave, as a funded organisation, is privileged to have and operate under. But I’m proud that it was difficult. The project was too good for us not to pay careful attention to it. It demanded time, risk and investment. This project was exactly what a shift away from tired festival and box-office models could look like. And I thank Accomplice, from the bottom of my heart, for challenging me to step up to the plate with them, and for making me better at my job.

Next Wave commits to and celebrates the chance to turn the spotlight away from the east coast, and shine it on territories and people who are already light years ahead in using the practice of care to curate artful experiences for their local community.

The lady at the samosa shop tells me, “We’ve never seen the big, fancy Darwin Festival here, it’s so good that this time they’ve come to us. Usually we are too busy cooking early in the mornings and closing late at night to enjoy the festival.” When Britt Guy walks through the Rapid Creek Markets the stallholders know her by name and the landlord trusts her with his only set of keys. This is the kind of relationally led care that Next Wave looks up to and is privileged to work with.

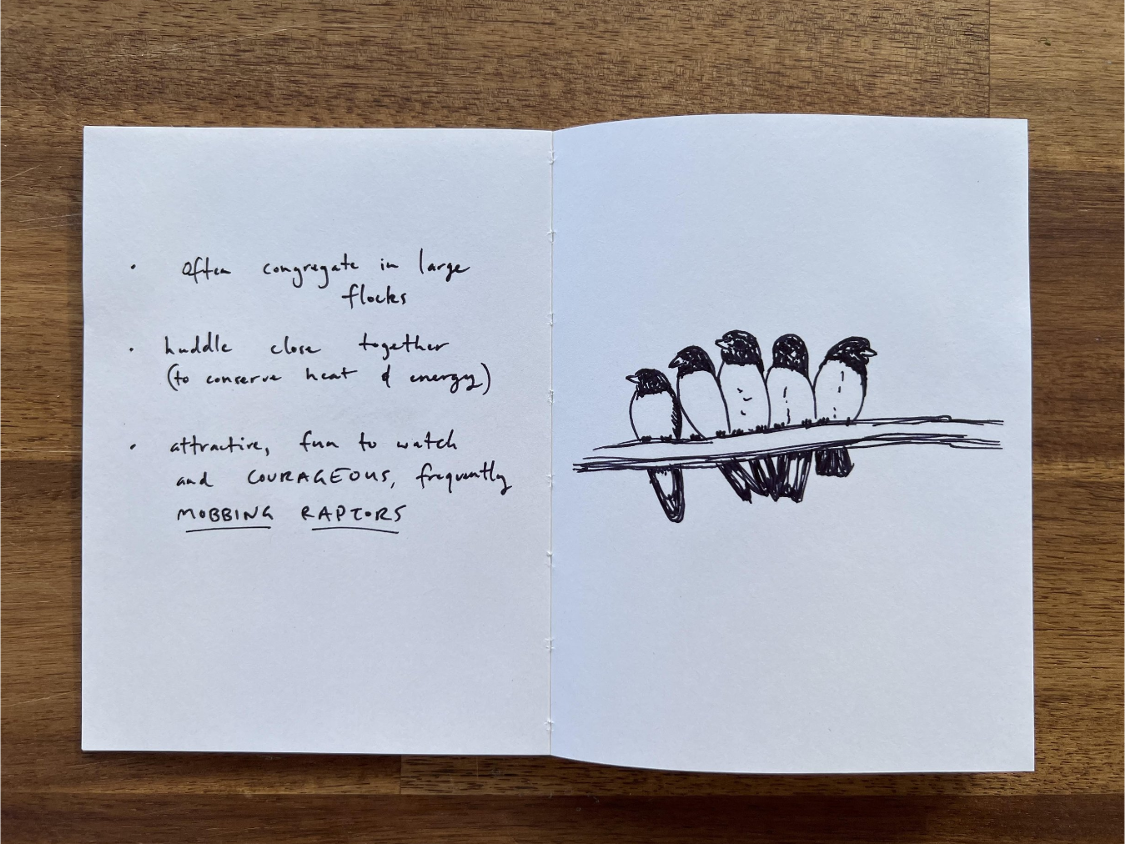

Nathan Stoneham, Notes from 'Art on the Wing', MarketMarket, presented by ACCOMPLICE and Next Wave, 2023

If you want to find tangible examples of how to curate with care, you don’t need to look very far at all. Perhaps start by listening to your own birdsong. I don’t have anything new to tell you that isn’t already happening in your communities. Care is local, and it begins with how you treat, see and hear one another. It begins with where you are in Time and Place.

Responding to the days we spent with Nadine, Accomplice and the artists on Larrakia Country, artist Nathan Stoneham wrote:

On a birdwatching walk, the MarketMarket artists admired and anthropomorphised the white-breasted woodswallow; especially the way they snuggled in groups. We drew parallels between their lives and ours — how we come together and separate, assemble and disband. What we didn’t see, was them MOBBING raptors to protect themselves.

Care’s not all cuddles and community … for the white-breasted woodswallow, care also involves aggressive action against dangerous threats. At Next Wave, we talk a lot about care. Cuddly care and clustering in communities is important. But we talk less about raptor-mobbing care. It got me thinking about the ways we care that are less socially acceptable — Queer care — non-normative care — illegal care.

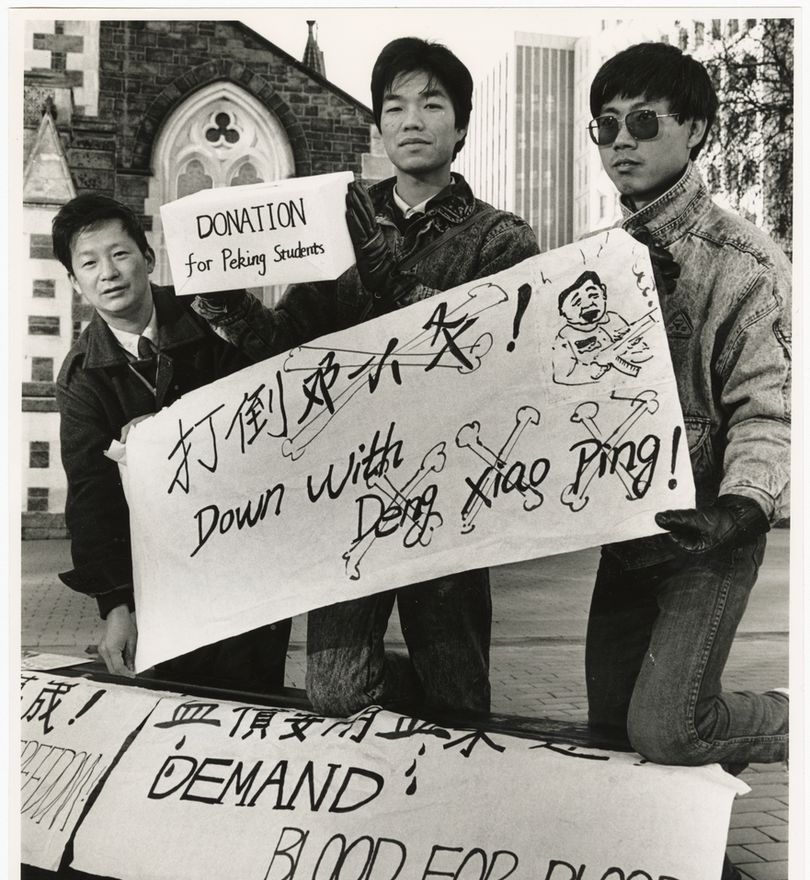

III. NOTHING BUT RESISTANCE MAKES SENSE ANYMORE

Having recently moved on from Next Wave, my feelings around artist care have grown even more complex. Small, nimble, artist-led organisations such as Basement and Next Wave found themselves in positions of immense privilege at the times the borders shut; both able to draw on their hard-won reserves to stop, slow down, and offer a soft, anti-box-office-driven approach.

Now we are in an entirely different crisis — the knock-on effects of this care have depleted the reserves (financially and energetically) of arts organisations and their workers. We have started to feel the knife-edge balance between care for artists and for arts workers, still searching for ways of working that protect both. Add to that the stark realities of Zionist influences amongst arts philanthropists, which make any attempt to operate ethically feel like a choke hold. Now we are realising how complicit we are in our unsustainability as a sector. If we say no to blood money, in what future will we ever be able to afford the privilege to stop and listen again?

But I am reminded by a peer that there is no point in making statements unless you know why you are making them and who you are making them for. And that listening is, in fact, free.

A few months ago, a Palestinian artist told me all she can do at the moment is sing; she wants to stop singing but she can’t. I’ve had a First Nations artist in crisis, with the ramifications of The Voice referendum starting to make their deep-seated presence in her body physically known — she calls it burnout, I call it white supremacy — and I’ve had a neurodivergent artist rail against the organisation with their full might for the ways in which we failed to tend to her specific needs.

I said to the Palestinian artist, “Of course, the venue is yours, no question, use it as you need, for your community of mothers and children.” In the background, security was organised at the last minute and my team volunteered their already overworked time to protect a singing and sewing circle from an ever-growing alt-right presence in the world.

The First Nations artist collapsed and didn’t deliver a final outcome. I reported to funders that she, in fact, over delivered, in a year when we should have insisted she rest instead.

I said to the neurodivergent artist, “I believe that boards should listen to artists not CEOs, because artists have the right answers.” She replied, “Artists don’t have the right answers. They have the right questions.”

‘Care’ is becoming one of these words about to die the death of the sector buzzword — we’ll see it among the ruins, alongside ‘intersectionality’, ‘innovation’ and ‘performative’. But I’d like to campaign to keep this word alive and do the hard work to actually understand what it means.

I think about doing my job so well that it becomes possible to sit in difficult cooperation with one another. As James Baldwin says, “We can disagree and still love each other. Unless your disagreement is rooted in my oppression.” Durable and long-lasting relationships are ones that can rupture and repair. They require acknowledgment, collaboration and action.

I want that angry care, rageful care, that illegal and illicit care, care that resists and riots in the streets or floods the inboxes of MPs with calls for a ceasefire. I want and need a criminal kind of care, one that is willing to dodge or even take the bureaucratic bullets for me, and relentlessly grind at not returning to the broken system we just came from. I need institutions to be prepared to step into the fire that I’m already in, instead of showing me where the fire extinguisher lives. And I want them to understand that their liberation is as much bound up in mine as mine is bound up in the liberation of Palestine.

A mantra often cited during our time in Larrakia was Pauline Oliveros’ phrase “Walk so silently that the bottom of your feet become ears.” It’s such a hard thing to do. To fall silent, to step back. To look. To listen. Once you truly begin to listen to each other, and to artists, you’ll never stop. You’ll be fucked mate!