Nathan Joe talks to Xin Ji about his life in dance — which criss-crosses China, Aotearoa, Europe and Japan — and the flashes of reflection that emerge in transit.

Xin Ji is a contemporary dancer and choreographer based in Tāmaki Makaurau. He has performed with a range of contemporary dance companies, including Footnote, Okareka, Muscle Mouth, Movement of the Human, Borderline Arts Ensemble and the New Zealand Dance Company.

At the time of this interview he was in Beijing, rehearsing with frequent collaborator Xiao Chao Wen on a new physical theatre work Look at Them! I talked to him over Zoom from Tāmaki Makaurau.

Look at Them! premiered on 20 June in Shenzhen, China, and is scheduled for a presentation at the Edinburgh Fringe Festival from 2–9 August 2024.

✺

Nathan Joe: Tell me about the journey that has led you to be a dancer here in New Zealand.

Xin Ji: I was born and raised in a city called Lanzhou, which is — if you look at the map of China, my hometown’s at the centre of the map. It’s a very industrial town. And none of my family members do art whatsoever. But, somehow, I just had this very strong energy — almost felt like I got chosen. I wanted to dance. I wanted to move. So, quickly, I just started dancing, and convinced my mum and dad to pay for my dance tuition. And I went to the audition for, and went to, the best dance school in China. When I was eleven, I went to Beijing Dance Academy for six years. Intensive training, all day, every day.

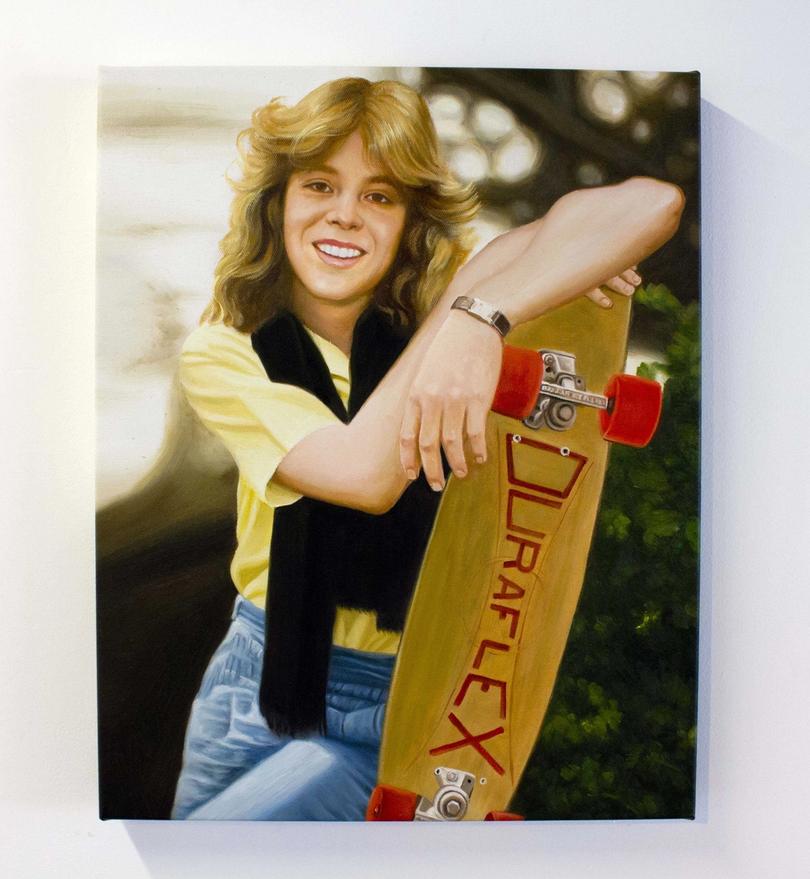

Xin outside Beijing Dance Academy, 2000

Photo by Xin's parents

So, skip primary school, skip middle school, skip high school. Training, training, training. Six years, all day, every day. I went through my graduation, then the moment I got my degree I went for an audition hosted by a Japanese musical theatre company, which is the biggest musical theatre company in Asia. They basically buy all the musical rights from Broadway, from the West End, you name it, they have them all. So I went for an audition, passed, and ended up moving.

Training, training, training. Six years, all day, every day.

Xin in costume as Mr. Mistoffelees in Cats, during his time in Japan

Photo by Xin Ji

Back then I was so naive and I didn’t even think about what I really liked. Because now I’m asking myself, Do I like musicals? I don’t at all [laughs]. I just thought, Amazing, I’ve been training for six years. I want a platform as many times as possible. And the musical really gives me that. I was there for about five years and I did over a thousand shows.

NJ: Oh my god. Which city was this in?

XJ: The company is based in Tokyo, but I lived in Yokohama, which is right next to Tokyo. You get to travel, you get to tour in many different cities. So I did that and had a really bad injury in the fifth year there. And this, you know, this involves a little bit of Japanese culture in that they pay you incredibly well. The society treats arty people as gifted. So they pay you really well. They look after you really, really well. But, on the other hand, they treat you like a product. Get back on the stage, no excuse.

So that forced me to quit my job. And then I realised, Oh my god, I’ve been working so intensively for the last five years, I want a completely different lifestyle. So my original plan was: go to New Zealand, learn how to speak English and get a degree, and then move to Europe. So I went to Unitec and I did my studies.

NJ: What did you do? Dance?

XJ: Yeah.

NJ: You’ve studied so much dance, you’ve done so much dance training in your life!

XJ: Yeah, that’s the only thing I’ve been doing my entire life.

I was there for about five years and I did over a thousand shows.

NJ: So what was the dance training that you did at the Beijing Academy versus Unitec? What kind of style was that?

XJ: When I was in Beijing, I did Chinese classical ballet. They teach you a lot of different things, such as Peking Opera, they teach you ballet, they teach you tricks and they teach you gymnastics. They do a lot of physical training. They prepare you to become the best dancers in the world. That’s their goal.

But at Unitec, it’s all about contemporary [dance], it’s about choreography, it’s about making your work, it’s about who you are as a choreographer, your own expressions. The first year, I hated it. I hated it because everyone around me made me feel like I was the most uneducated idiot, because I hated the way they moved. I hated [that] everyone was so confident. I hated [that] everyone had the best ideas in the world. I didn’t know what to do.

Xin performing Uku — Behind the Canvas for the New Zealand Dance Company

Photo by John McDermott

Now, looking back, that was my first, biggest, culture shock. Because in Asia, being Asian, it’s about being excellent, being the best of the best, but they give you the handbook and tell you how to become the best. There’s always a model of what the best looks like. But the moment I arrived in New Zealand, and went to Unitec, there was nothing right or wrong.

It’s about … What do you want? What do you want to do? And your reason behind it. You can be the most weird shape, and then people still think, Oh, I really like that.

And I was like, How!? This is so ugly! I don’t know, someone just stood there, you know, stuck their tongue out, you know, they did nudity, and I was like, What’s going on? and that was the biggest culture shock for me. And then I got to the second year and I think my mind finally opened and just accepted things. That’s the moment my old system just kind of crumbled.

I hated the way they moved. ... You can be the most weird shape, and then people still think, Oh, I really like that.

NJ: That’s quite beautiful. And what year was it when you moved here?

XJ: I moved to New Zealand in 2010. It was a long time ago, a long time ago, and then the plan completely changed because I got offered a full-time contract with the New Zealand Dance Company.

Then the pandemic kicked in and that’s when the shift really happened, to give me time to reflect, Oh my god, I’ve been organised by others. By companies and, you know, being consumed by saying yes to all the projects in the past.

I didn’t really ask myself, What do I like as an artist? What do I want to say as an artist? As a person? As a performer? And then I think my urge of making work finally arose and arrived in a certain way. Then I started shifting myself and seeing fewer performing jobs and seeing more choreographing jobs.

Poster for Stage of Being, which featured Made in Them, choreographed by Xiao Chao Wen & Xin for the New Zealand Dance Company, 2023

Photo by John McDermott

So now I’m in the middle of the transitioning period. Just seeing how I can balance both needs and passions, dancing while choreographing and making. But, now … my lifestyle completely changed post-pandemic. How am I going to put food on the table while I’m doing what I love?

Ideally, I wish I could stay in New Zealand, all year long. Because I just love the freedom, I love the people around me, I love the environment that inspires me so much. But being an artist in New Zealand … impossible, impossible. Yeah, impossible. It’s really sad.

I didn’t really ask myself, What do I like as an artist? What do I want to say as an artist? As a person? As a performer?

Xin performing The Fibonacci for the New Zealand Dance Company, 2022

Photo by John McDermott

NJ: Do you see yourself as being based in New Zealand, though, in the long term?

XJ: Yeah.

NJ: What happened there? What made you decide that? Because originally the plan was, you said, to just learn English, do some study, and then move to Europe.

XJ: One thing I’ve realised is that, when I was a dancer with the New Zealand Dance Company and I went to Europe a couple of times, l just realised it was very similar to Beijing. It’s very similar to what I am used to. The vibes are similar. It’s very cut-throat. Auditions are about who knows who, it’s about who’s got the best flexibility, who’s got the most amazing connection. You need to be noticed, you need to project and let people know you’re the best mover in town, therefore you’ll get jobs. I think, after being in New Zealand for so many years, I just realised, there’s so much more than that.

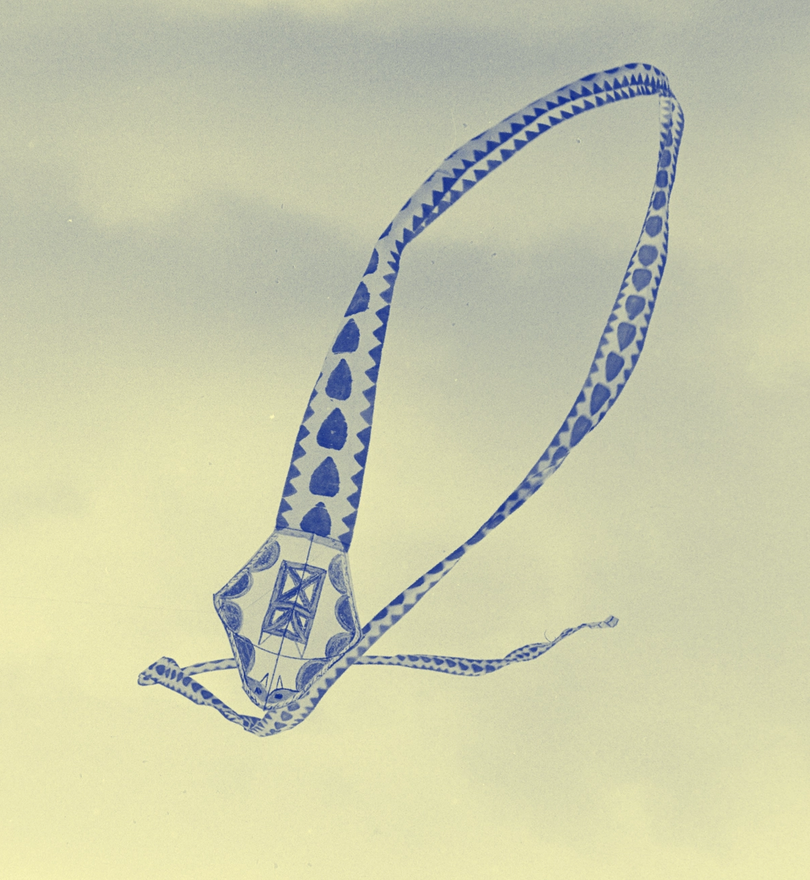

Behind the scenes rehearsal for Look at Them!, 2024

Photo by Fu Xiao

NJ: And what is that so much more? Can you define that? Maybe that’s a big ask.

XJ: I grew up in the concrete world, in the mega city, living the busy life, and living in Japan. You know, the busiest city in the world. And then I went to New Zealand and that’s the first time I realised as a human being that life can be so wonderful. I can just go to the beach and do nothing. Take a book and just sit there, and someone’s dog just comes to lick your face. You know, all those things that used to be in the movies, in the stories, in the books. And now they’ve become so accessible and so easy.

I think, also, one thing I love about the Kiwi lifestyle is that everyone minds their own business. So you have so much space for yourself that I never had before. The moment I arrive in Beijing, I am being consumed. I am immediately being consumed by things, by projects, by people. They want to get you involved because they want something from you. And that’s a good thing because you are valuable. And then people chase the money. Chase the fame, chase taste, chase the connection. And I don’t want to live that way.

You know, people talk about the Asian mentality. And the moment I come back to Asia, it’s a thousand times more than that. It’s beyond a mentality. It’s in practice, it’s in expectation. It’s in the … even the air. I can feel even the air runs a bit faster. Just speed. Nothing slows down.

The moment I arrive in Beijing, I am being consumed. I am immediately being consumed by things, by projects, by people.

Behind the scenes of the dance film Beijing

Photo by Dani Hao

NJ: How have you maintained or kept professional opportunities alive back in China?

XJ: It actually started from my first job. My first gig was five or six years ago. One of my old colleagues that I met in Japan had this opportunity to choreograph, to direct a brand-new musical, an original musical in China. And that was my first job as a choreographer, to come in to help choreograph the whole musical.

NJ: Oh, wow.

XJ: That was so interesting and a big challenge. I loved that. And that was a huge shock. Shocking in every single way. I got paid incredibly well. Just as a normal, random, choreographer for a musical. So, financially, yes, that was amazing. But creatively that was a disaster. So that was my very first gig. And after I tasted that I was like, Nah, I can’t do that. It destroys me as a human, it destroys me as an artist. Every single way you don’t want to be, that’s what that’s about.

NJ: So was this your first job out of Unitec, or your first job as a choreographer?

XJ: First job as a choreographer working in China. And after that, I said to myself, Yes, money is important, but I have to be really selective about the projects I say yes to. So now I’m only saying yes to the jobs that really interest me as an artist, as a human, and I know I can be guaranteed creative space. When I’m working with my best friend, Chao, I know that I am guaranteed that space.

Xin and Chao

Photo by Solomon Mortimer

NJ: How did you and Chao begin collaborating?

XJ: Unitec built a relationship with Beijing Dance Academy, so each year they would send one or two students — exchange students from Beijing — to Auckland. So when I was a first year, he was the exchange student that got sent in to study. And he was meant to be in the second-year class, but then he couldn’t speak English at all, and the school thought that would be too hard for him to be in a completely stranded environment. So, let’s make his life easier. He got chucked in my class and we immediately became best friends because we share very similar passion and optimism about being an artist, being a choreographer, and having such expressions we want to share with the general public. We immediately became besties.

NJ: You’re in China at the moment. Do you think you’re rehearsing and making your current show differently than if you were New Zealand?

XJ: A huge difference.

NJ: What changes it? Just because of the dancers? Or is it the environment?

XJ: I think it’s just the environment. As I told you just before, the moment I arrived here [in Beijing], I just feel like everything runs a bit faster. People talk a bit faster. I just feel like, being here, immediately I feel pressure. The people are less brave, less critical. People just, like, obey. I can feel the pressure. I can feel the anger that builds up in everyone. In certain sections of the work, we try to bring out all those things. Let them explore. The explosion in every single one is incredible. It’s almost like individual volcanoes.

But if you take people in New Zealand — like, for example, Chao — the moment Chao arrives there, he sleeps better and his mood is a bit softer. Immediately becomes happier. The work we’re making is, oh, a bit slower. Everything. The mood is changed, the pressure’s changed, the qualities change, the ideas are changed. I think this gives a very unique identity to this work we’re making.

I can feel the anger that builds up in everyone. ... we try to bring out all those things. ... The explosion in every single one is incredible. It's almost like individual volcanoes.

NJ: What’s the value of your training in China when you come into New Zealand environments? When you’re working with New Zealand choreographers, what is the quality you bring into those spaces that you think is useful or surprises people?

XJ: I think the most useful thing I can bring is … it’s the training, it’s the body. I’ve been training since I was like eight years old. The way I deal with my body is with a bit more familiarity than the [other] people in the room. I’ve had so many injuries in my life so I know how to manage them. I had a broken rib and I did a whole season.

Xin rehearsing If Never Was Now with the New Zealand Dance Company

Photo by John McDermott

NJ: And the work you’re currently creating, is it specifically created within the context of being shown in China, or is it a work you’ll do over here? Would you even bring it over here?

XJ: At the moment, we’re trying not to think about where the market is for this production. I think we just want to make it as authentic as possible, then we’ll think about the consequences later, because there are so many things. It can be dangerous, can be challenging, and we’ll see.

Look at Them!, 2024

Photo by Fu Xiao

NJ: As an independent maker in New Zealand, are you interested in making your own work here? Getting funding, finding a producer, doing that sort of thing? Is that of interest to you?

XJ: Absolutely. I used to hate solo shows. I watched so many solo shows. I always thought it was like the last thing I was going to do in my life. I always envy the artists who can make solo shows and carry the whole process. The pressure on one person’s shoulders. But, somehow, I have this urge. It’s a weird thing. It excites me. It’s petrifying to even think about it.