Patience and attention lie at the heart of bonsai artist Steven Yin’s practice. Here, he reflects on coming to know a place through its trees and shares his philosophy on the ongoing development and growth of the bonsai and penjing artforms in Aotearoa.

My family immigrated to Aotearoa when I was little, and in our first five years here we moved around a lot, always struggling to make ends meet. We each faced our own set of challenges. For my parents, finding suitable work with limited English was incredibly tough. As for me, I went to three different schools in two years and was constantly thrown into new environments without knowing a word of English, so I had to adapt quickly.

Growing up, I developed a deep fascination with insects and plants. In Aotearoa the insects are much smaller compared to those in China — cicadas, praying mantises and crickets are only about one third the size of those in Beijing. Back home, I had numerous potted plants, but the unfamiliar plant species here initially left me feeling disconnected.

Artist unknown, boy carrying an insect toy, c. 1800–1899. From a collection of Chinese drawings held in The New York Public Library Digital Collections (b13986156)

I had to adapt quickly.

Suzuki Harunobu, scene from the noh play Hachi No Ki (The Potted Trees), 1766-1767, woodblock print

However, in high school, I stumbled upon bonsai and penjing plants, which I began to care for like pet trees as we weren’t allowed to have pets in our rental home. Twice a year, I’d give them a trim to keep them neat. Although I loved caring for them, I didn’t fully grasp the true significance of these horticultural artforms, nor the science behind cultivating miniature trees, until later on. Nonetheless, the trees flourished, gradually coming to resemble majestic old trees while maintaining their small size.

As I delved deeper into these practices, I developed a profound appreciation for the patience and mindfulness required to cultivate and to nurture these miniature trees. Similar to the giant old native trees growing on the land of Aotearoa, bonsai and penjing trees embody a sense of history and resilience, symbolising endurance and adaptability. Both bonsai and penjing seamlessly blend nature, culture and tradition, and I became deeply intrigued by these aspects, realising that these practices offer more than just aesthetic pleasure; they serve as bridges connecting diverse cultures, environments and landscapes.

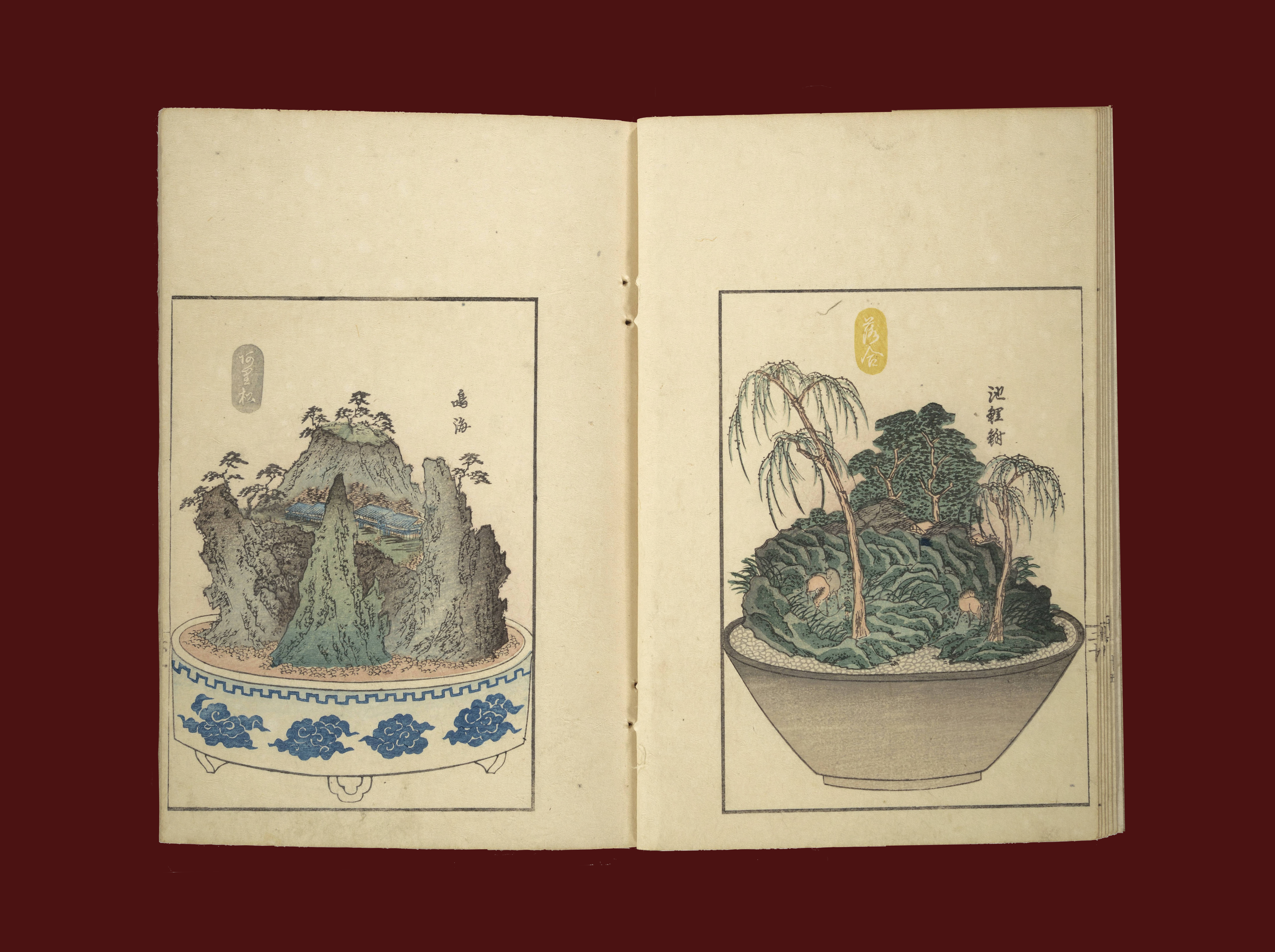

Japanese bonsai derived from Chinese penjing approximately 1,000 years ago, with both practices involving the horticultural study of trees to mimic nature on a miniature scale, although the scale and level of detail vary significantly between bonsai and penjing. Bonsai focuses on creating structurally and aesthetically powerful trees according to specific rules developed for this artform, while also scientifically respecting the tree’s overall health. A well-crafted bonsai tree should reflect the environment it would naturally grow in, with its shape influenced by environmental factors such as strong wind, thunder and drought. Penjing, on the other hand, incorporates rocks, moss, dwarf plants, mudmen figurines, or even different tree species to create miniature landscapes.

Every tree's body and its branch structure narrates its survival journey.

Mizu no Genchuukiyou and others, ideal form for a pine tree in the Bunsei era, from Somoku Kinyoshu (The Bonsai Books), 1829

Practising bonsai and penjing has taught me a great deal about nature. I’ve learned that trees hold valuable information; by observing their growth patterns and the condition of their leaves, one can decipher the story of their past experiences and present condition. Every tree’s body and its branch structure narrate its survival journey.

I have travelled to Indonesia, Southern China and Japan multiple times to visit bonsai nurseries, and have studied the differences in how miniature trees are cultivated by different cultures. Although these practices originated in Asia, they can be applied to any culture and landscape. By understanding their fundamentals, and by drawing inspiration from my surroundings, I can create miniature landscapes that capture the essence of our native environment in Aotearoa.

I normally spend a year observing any new tree

All trees, including Aotearoa native species that were unfamiliar to me, can be used for bonsai or penjing. I treat each new tree with respect, much like the way we should treat individuals from different cultures — embracing differences and seeking to understand each other’s perspectives and boundaries. I normally spend a year observing any new tree before making design decisions, during which I care for it, study its growth habits, and learn from simple observation. I believe that by taking the time to familiarise myself with each living being — also allowing the tree the time to adapt to me — we can achieve wonderful things together in harmonious ways.

Through observation and exploration, I’ve discovered that some Aotearoa species, such as tōtara, bear similarities to the Chinese Buddha pine, and our national flower, the kōwhai, resembles the Chinese Caragana plant in penjing practice. These discoveries have drawn me closer to making Aotearoa my second home outside of China, demonstrating that we can treasure our differences, but also find connections and similarities if we seek them.

Utagawa Yoshishige, Tōkaidō gojūsantsugi hachiyama zue (Views of Instructions for Bonsai along the Fifty-three Stations of the Tōkaidō), 1848, woodblock printed book. The Metropolitan Museum of Art (2013.863a, b)

Steven Yin, still from The Generation Gardener, 2023

Photo by Celeste Fontein

After my father passed away in 2019, I set a goal to pursue bonsai and penjing as a career. As well as cultivating trees for sale, I teach educational workshops for people interested in learning bonsai as a recreational hobby. I’ve noticed that many people love bonsai and penjing but struggle with understanding all the rules and schedules associated with them. Recognising that we all live busy lives, I believe that practising this art should complement rather than hinder our lives.

While bonsai and penjing require discipline in aspects such as watering and feeding, the artistic aspect should be approached on a personal level. Everyone perceives nature differently, and there are no rigid rules about how a tree should look. Therefore, rules regarding bonsai structure should be secondary. Just as finding balance in life is key to happiness, the same applies to bonsai and penjing practice — finding a balance between intervention and allowing the tree to thrive on its own. I believe, for bonsai and penjing to flourish in Aotearoa, we must adapt our practices to suit the local demographic, reflecting Kiwis’ relaxed, go-with-the-flow attitude to life. Chinese penjing, which primarily involves clipping rather than shaping trees with wires, shares more similarities with the easy-going Aotearoa lifestyle.

Steven Yin teaching a bonsai workshop, behind the scenes of The Generation Gardener, 2023

Photo by Celeste Fontein

My journey with bonsai and penjing has not only deepened my appreciation for nature, but has also bridged the gap between my two homes, Aotearoa and China. Through these practices, I’ve discovered similarities between the landscapes, flora and cultural nuances of both countries; by embracing our differences and celebrating our similarities, we can forge stronger bonds and new ways of expressing who and where we are.