Ankita Singh stumbles into a writing routine, only to watch it slip away just as the deadline for her first play looms. Here, she shares what she’s learned while trying to find her way back, and explores the deeper question: What does it really mean for an artist to be ‘productive’?

I started taking writing seriously during lockdown.

I’d just begun my Master of Creative Writing. We were two weeks into the course when the first lockdown was announced.

As depressing as a global pandemic was — turned out, this was the perfect environment for cultivating a writing practice. No one to see, no shows to go to, and no work on the horizon (thanks student allowance). For the next 12 months I was forced to focus my attention on one thing and one thing only: finishing my master’s, which entailed writing a feature-length screenplay.

While the world was being irrevocably reshaped, I was pottering in my little bubble, subconsciously developing a routine for the first time in my life. Without anyone on my ass I’d leisurely wake up at 10am, do some yoga, make a coffee, and sit down to write five solid pages every day. Then I’d go for an evening stroll in the park, come home, make dinner, maybe even bake some banana bread, relax, read or study a hobby till midnight, then sleep and repeat it all the next day. My class would also meet regularly over Zoom to conduct table reads and discuss progress and ideas.

I was able to knock out my script (and then a second draft) with little friction. I thought I had locked in a perfect writing practice.

Everything was perfect. I was a writer who wrote, goddammit!

Then … it all went to shit when Covid restrictions were eased and I was ushered back into reality.

❉

With no more student allowance, freelance gigs piling up, friends, shows and cafés to visit, my perfect little writing routine was quickly annihilated by the everyday rhythms of life.

Allgood. I thought. I’ll fit it all in.

So I did. For a little bit. I took up producing again while trying to balance writing and every other obligation that would land in my inbox. Time fragmented into endless little shards.

Five pages became four, then two, then none. I’d stare at emails for hours before responding to them. Brain fog all-consuming. Doom scrolling became my main hobby. The brain rot settled back in.

I knew it was bad but couldn’t stop. What the hell was wrong with me?

Eventually, I resorted to my tried and true strategy for getting shit done: using intense fear and spite to push through exhaustion. Deadlines and pure resentment motivated me to write late into the night — to prove people who’d done me dirty wrong.

I’d show those assholes how productive I was … by ruining my sleep schedule, sitting for eight hours straight and eating one meal a day.

This was obviously a far cry from my peaceful little cottage-core lockdown routine. And obviously not healthy. But what other choice did I have? I had to hustle and keep all the plates spinning.

Sure, it worked for answering emails and organising production logistics, but this strategy was completely useless when it came to tackling the biggest project of my writing career.

My first play.

So high up you’re literally above the clouds — far, far away from the world and all your annoying emails. Parwanoo, Himachal Pradesh, 2023

Photo by Ankita Singh

When it came to writing BASMATI BITCH, constant distractions and lack of structure held me in a writer’s-block choke-hold for months.

Luckily, I had planned a trip to India around that time to visit my mum. Even more luckily, she and I had a massive row not long after I landed. I decided to take a week to retreat to the hills there to get some space.

Ah, the hills — well, we call them hills but they are actually the foothills of the Himalayas, i.e., bigger than most mountains you’ll see in Aotearoa. Quite a drastic scene-change from my inner-city apartment.

I was the only person in the hotel I was staying at — alone, surrounded by picturesque views of misty mountains, giving me the mental clarity I needed to focus. There I spent a considerable amount of time reading a stack of books I had brought for research and contemplating the ideas presented in them. During this time, I was able to come up with the underlying theme for the play.

Unfortunately, running out of money and having to leave the beautiful retreat, I was soon thrust back into normal life and struggled to write anything. Again.

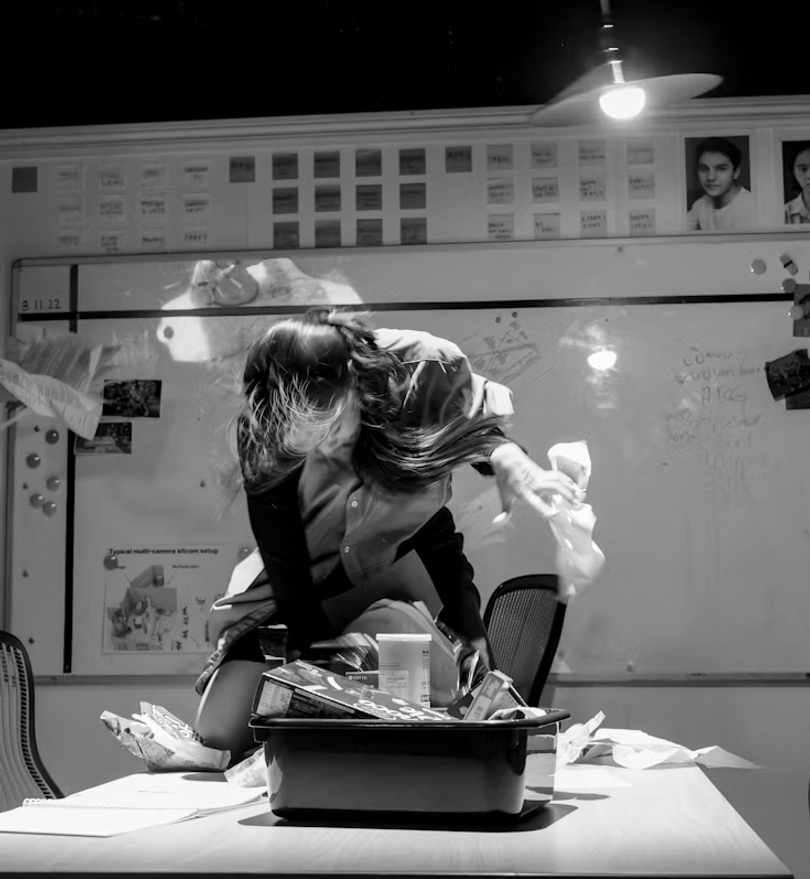

The desk where the magic happened — a far cry from a scenic mountain resort. Ankita's apartment, Auckland CBD, 2023

Photo by Ankita Singh

By the time I landed back in Aotearoa, I had constant stomach cramps from stress. I had little over a month left to deliver the script and I only had the theme. In pure desperation, I called upon my master’s supervisor to give me some advice. This, coupled with an afternoon spent with a friend knocking out the structure gave me the outline of the play. Now I just had to write the damn thing.

With a deadline looming and unable to focus, I decided I needed to recreate the routine I had discovered during lockdown — to hold on to what remained of my sanity and make sure I was making consistent daily progress.

I shut down my social calendar, turned off my phone and devised a routine:

Wake up 10am. Make coffee. No time for yoga. Light incense. Pray to Ganesh (the remover of obstacles). Sit down to write, only stopping for lunch. In the evening go for a walk in Victoria Park for 1–2 hours. Question all my life decisions. UberEats dinner. Light a candle to keep me company. Write till midnight. Call my boyfriend for emotional support. Cry. Sleep. Repeat.

I was miserable, and I’m pretty sure I cut two years off my life, BUT I managed to hand in a usable script a month later, just in time for rehearsals.

Watching a tech run of BASMATI BITCH and having an out-of-body experience seeing my words brought to life by all these talented people, Q Rangatira, 2023

What was the difference between writing my feature and the play? Why had I struggled so much, for so long, despite knowing there was a routine that worked for my writing practice?

You’ve probably already figured it out — Ankita, you’re saying, there’s a huge difference between writing while being forced to stay inside for months and trying to write in non-pandemic life conditions.

But surely I could continue to write, even without a global pandemic being my covert patron. I HAD to figure out how to replicate my lockdown process ‘irl’, if you will, so I could avoid repeating the soul-crushing experience of having less than a month to deliver a 90-page script.

❉

I recently read Deep Work by Cal Newport, lent to me by a friend, and a lot of things suddenly began to make sense about my experiences. Deep work, defined by Newport, is work that generates new knowledge by pushing our mind to its intellectual limits. This type of work creates value for a society, industry or community. Basically, in this book he argues we’re living in an era where attention is the biggest commodity — and attention is exactly what’s needed to create meaningful work.

Reading this book, I realised I had accidentally stumbled upon the four rules of deep work that had allowed me to write my screenplay and BASMATI BITCH.

Lord Ganesh watching over me — alongside a lovely, well-used incense holder by Steven Junil Park, 2023

Photo by Ankita Singh

Four Rules of Deep Work

1. Work Deeply: Establish rituals and routines that promote deep work.

Hello walks in Victoria Park and prayers to Ganesh.

2. Embrace Boredom: Train your brain to tolerate boredom and avoid distractions.

Certainly, lockdown and yoga had been this for me.

3. Quit Social Media: Minimise the use of social media and similar platforms that fragment attention.

I had done this out of pure desperation.

4. Drain the Shallows: Be intentional about how you spend your time and protect your capacity for deep work.

This last rule struck me like lighting — during lockdown, all my intention was directed at my writing and looking after myself.

Outside of the lockdown, I had been completely unintentional with my time, saying yes to any hang-out, constantly checking my emails throughout the day, and allowing everyday life to erode the things I knew helped me write: saying yes to a 9am meeting when I knew I needed the extra sleep, saying yes to seeing an evening show when I knew I needed my evening stroll to clear my head, not demanding we make room in the budget for a writing buddy or script supervisor when I knew I needed one.

I was deprioritising my routine, my process, because I didn’t really think of myself or my needs as a priority.

This lack of structure, lack of priorities, unintentional use of my time — whatever you want to call it — meant I couldn’t enjoy quality time with family and friends because I was thinking about work, and I couldn’t work effectively because I was thinking about all the other shit I had to do.

What a mess.

❉

Bollingen Tower, built by Carl Jung at Lake Zürich. CC BY-SA 4.0

Photo by Davide Mauro

You know, my mum has always told me, when someone asks you to hang out — even if you’re free and keen — two times out of ten you should say no. You have to teach yourself and others that your time is valuable and not always up for grabs.

Time and space. The ultimate elusive luxury. Essential for writers — as many have noted before me.

There are countless stories of writers retreating to a room, tower or cave to create some sort of masterpiece — Carl Jung famously retreated to an actual tower he built to form his theory to battle his contemporary, Freud. Bon Iver retreated to a cabin in the woods to write his critically acclaimed first album. Virginia Woolf famously argued a writer needs ‘a room of her own’, ‘a lock on the door’ and money to keep it there. Spiritual gurus have similar stories of isolation leading to breakthroughs — Buddha’s self-imposed exile and intense meditation come to mind.

From my observation, it’s not the physical room, or even isolation, that’s important for creative work, but what that room allows to happen.

That thing is focus and deep contemplation. Pushing our mind to its limits. That’s the key to not only starting and finishing a project but ensuring it has value.

Many people assume writing is a solitary activity, but I’d argue the most important stuff happens in the heat of debate and conversation.

Workshopping the script for RABID at the Rocket Park Writers Lab, with Karishma Grebneff, Sneha Shetty and Ahilan Karunaharan, 2023

Photo by Calvin Sang

This type of mental depth does not require isolation, in fact it sometimes requires partnership. In his book, Newport describes the partnership between experimentalist Walter Brattain and the quantum theorist John Bardeen, ‘who over a period of one month in 1947 made the series of breakthroughs that led to the first working solid-state transistor.’1

Brattain and Bardeen worked together during this period in a small lab, often side by side, pushing each other toward better and more effective designs …

This back-and-forth represents a collaborative form of deep work (common in academic circles) that leverages what I call the whiteboard effect.

For some types of problems, working with someone else at the proverbial shared whiteboard can push you deeper than if you were working alone. The presence of the other party waiting for your next insight — be it someone physically in the same room or collaborating with you virtually — can short-circuit the natural instinct to avoid depth.2

This method of partners pushing each other to deeper and deeper thinking immediately reminded me of Socratic questioning — an educational method that focuses on discovering answers by asking questions between two or more people — digging for the essence or truth of whatever is being discussed.

I experience this type of partnered deep work and Socratic questioning taking place in writers’ rooms, when speaking with a script supervisor or dramaturges or writing partners.

This is why those lockdown table reads were so useful!

Many people assume writing is a solitary activity, but I’d argue the most important stuff happens in the heat of debate and conversation. I find working with a partner has been the most effective technique for most of my projects, from writing films, plays and TV shows to university essays. Taking the time to truly dissect ideas, themes and structure is, to me, the most important part of writing — and it often occurs long, long before you ever put pen to paper.

And hey, you may prefer just the monastic approach, but understanding these different ways of working and when to utilise them — heck, even knowing different methods exist and are valid — can help you build your own unique writing practice.

I am sure we can all agree that the grind of modern life, a nine-to-five, family responsibilities, bills and social media make it seem nearly impossible to cultivate a habit of focus. But it’s not impossible. Even an hour every day can add up, like the journalistic approach mentioned in Deep Work.

In a perfect, or even slightly better, world, we’d all unionise and advocate for a universal basic income — until then, I hope all this illustrates that physical or mental isolation is actually not required to be an effective writer. What we should be focusing on instead is discovering the personalised technique that cultivates our own ability to go deep — then doubling down on it.

The first step you can take is to consciously commit to learning about your own process. Learning about the self is actually crucial to writing, in my opinion.

Behind the scenes of the BASMATI BITCH trailer, 2023

Photo by Ankita Singh

I was a pretty happy kid before we immigrated to NZ where I was unfortunately subject to social isolation and bullying — the glasses and extra chub made me a prime target

Mental health and productivity culture

Before we move on, I want to talk about mental health.

In the past five years, I’ve written and produced several films and theatre shows, a TV series, and countless funding applications, pitches and reports. My output is objectively high for a creative, but in my mind, I perceive myself as an unmotivated, lazy, unsuccessful person — what gives?

Even though I’ve lived a relatively cushy life, my childhood was unfortunately marred by intense bullying and social isolation. I remember being depressed before I was even in middle school. In retrospect, these early experiences have left me with a fairly poor self-image.

On a quest to ‘fix myself’, I’ve become obsessed with psychotherapy videos on YouTube. In particular, I am addicted to Dr Alok Kanojia’s video lectures. Dr Kanojia, also known as Dr K, combines Eastern philosophy and yogic principles with Western psychiatry. He covers everything from gaming addiction to modern dating, and most interestingly, trauma and its long-term impacts on our wellbeing and our ability to be productive.

I am currently directing a doco about The Dunedin Study, a 50-year longitudinal study on human development, and it confirms the same findings Dr K so often speaks about from his clinical experience. Trauma, especially trauma caused by adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), has lasting effects well into midlife and beyond.

Trauma and resulting maladaptive behaviours can negatively impact the trajectories of our lives — literally increasing our chances of developing mental and physical illness, and even making us age faster.

This was all a little concerning till Dr K hit me with one of his most insightful takes: that maladaptive behaviours aren’t the mind being ‘broken’; in fact, they are the mind behaving exactly as it’s intended to. Behaviours that help us survive, such as dissociating, are useful in situations where we have no control over our environment. These survival adaptations become maladaptive later in life, when we exit that environment and do have control, because they do not help us thrive.

Thriving requires self-belief, planning (aka imagining the future) and breaking down big goals into small everyday tasks. When you are in survival mode, you don’t think about the future, you live moment to moment — you’re just trying to get through the day.

Being in hyper-alert survival mode, obviously, does not produce the ideal mindset for productive goal setting — such as aiming to write five pages a day till you have a full script.

In the hills, contemplating my bad decisions

On reflection, I broke one of my maladaptive patterns when I decided to go to the hills for a bit after the row with my mum. If the environment isn’t working for me, I realise now as an adult, I can change it!

The Dunedin Study has found that 86 percent of adults will experience some form of diagnosable mental illness by the time they are 45 — anything from depression or anxiety to ADHD, schizophrenia or substance dependency. This tragically means most of us will suffer eventually, probably in silence.

I’ve observed many artists and writers in my life who are marred by trauma or low self-esteem. We often find ourselves subconsciously drawn to creative pursuits because of our experiences — after all, art is often just self-therapy in disguise. Or maybe we’re on a self-righteous crusade to make sure people like us don’t feel alone, or whatever. Many of us also struggle to break ambitious ideas down into achievable steps, initiate projects, draw boundaries or get work done unless we’re under the intense pressure of external deadlines or have a producer on our asses. What is underlying this behaviour?

My hypothesis is that many creatives not only battle with modern-day distraction but also maladaptive behaviours caused by trauma. Brain fog, inability to focus, hopelessness, negative internal monologues, fatigue and procrastination can all be indicative of this.

Look, I am not blaming it all on trauma, BUT I just think it’s interesting that the effects of mental illness are hardly ever discussed in the productivity niche, even when it’s so common. Hmm, could it be something to do with this niche being full of ‘minimalist gym-bro thought-leader’ types? Hmmm …

Anyway, I am telling you all this because, for the longest time, I believed my lack of ability to plan and structure my life was a personality deficiency — a failing of moral character. I was just too lazy or too stupid to get my shit together. Turns out, it wasn’t my moral failing getting in the way, but some wiring of my brain that helped me adapt and survive one situation, but had become maladaptive in a new situation. The good news is that I am not broken, and neither are you. We just need to rewire our brains.

Many of the productivity strategies I’ve stumbled upon — such as the four rules of deep work, and other activities and rituals that help one delve into a flow state — are the same kinds of strategies and rituals prescribed by therapists to help rewire minds that have maladaptive behaviours caused by trauma.

Being active, pushing your body, taking walks in nature, training your mind to focus through breathing, meditation, routine, rituals, embracing boredom, reprioritising your time and energy (boundaries!), cutting down on social media, journaling and doing repetitive tasks involving your hands — these are all strategies suggested by Dr K and other psychiatrists to basically calm the mind, train it to focus in the present, and allow it to process emotions and rewire. You may have noticed — these are some of the same strategies suggested by Deep Work to get into a state of mind that allows you to focus, contemplate and create work of value.

Ancient solutions to modern problems

What’s even crazier to me is that these are the same practices many spiritual traditions suggest we cultivate to live a purposeful and meaningful life. Going within, prioritising cultivating our relationship with the divine (whatever that is to us) through consistent training of the mind through meditation, prayer or reading ancient texts, or physical rituals such as dance, martial arts, song or practising crafts. These actions require us to push our bodies and minds to their limits through deliberate practice, commitment, focus or deep contemplation. Their goal isn’t to be more productive but rather to cultivate a sense of purpose. This sense of purpose is ultimately what leads us to feel content with our lives.

When thinking of this principle, I’m reminded of a verse from the Quran I’ve heard from a few friends — ‘With hardship comes ease’ (94:5-6). Not after, but with as in alongside it. Dr K says the same thing — our brains like doing hard stuff. The mind wants to be challenged.

Vegetating on TikTok may give us a momentary dopamine hit, but our minds will not feel satisfied after an hour of it. Our minds probably would feel satisfied after an hour spent assembling a complex piece of Kmart furniture or trying to understand a new language. As my personal trainer says, ‘You gotta expend energy to get energy!’

Their goal isn’t to be more productive but rather to cultivate a sense of purpose. This sense of purpose is ultimately what leads us to feel content with our lives.

Many artists, athletes and writers have rituals around their practice — to almost superstitious levels. They must do certain things every day, in a particular order, with particular objects, to prime their minds to access their flow state. Whether it’s writing with a special pen with ink that flows just so, or a lucky pair of shoes that fits just right, or needing to walk in the park in the evenings to think through their latest script — it’s essential. Break their ritual and it’s like cussing a primordial God and losing access to The Muse.™

The conclusion I’ve come to is this: productivity specialists, therapists, monks and the like have all found the same medicine for what is essentially the same problem. A distracted, fractured mind will be unhappy and find it difficult to focus when required. It is essentially an unruly chariot, controlling us rather than us controlling it. A mind that is whole, present and content, that we can control, will be able to focus reliably and consistently, and produce value for us and those around us. It will be able to gallop in the direction we point it.

Willpower is a muscle, the mind is a muscle, focus is a muscle. We need to train it to do what we want. And every mind is different. Understanding your individual needs to train your mind, to improve your mental health and ability to be in the present, are directly linked to your ability to control your willpower and concentrate on any given task — including writing.

On the set of 'Give Me Babies' with Calvin Sang, 2023

Photo by Diya Beharie

Make craft and process the priority in your artistic life

Taking writing seriously has been a slow process of taking myself seriously.

Understanding my process has necessitated understanding myself.

Ultimately, connecting the dots between my process, deep work, and deeply buried traumas has made me realise what I need to prioritise in my life.

I don’t need a lockdown to write. I need to respect myself, and thus, my unique process.

Ten hours of sleep, a morning cup of coffee, an evening stroll, a writing partner — I used to think of these as silly little treats, flights of fancy. Now they are my rituals, all essential to my mental and physical health — and concrete non-negotiable fixtures in my writing process.

At the end of the day, writing is a craft and honing a craft is a spiritual process.

I’ve begun to slowly change as much of my life as possible to accommodate these rituals. It has meant changing some of my career goals and redefining what’s important in my life. Maybe that sounds like a cop-out to some people but, honestly, I feel better about myself and life in general now than I have in a long, long time.

At the end of the day, writing is a craft and honing a craft is a spiritual process. I am not talking ‘woo woo’ spirituality; I am talking about the need to go within and understand all parts of ourselves, especially deeply buried scars that could be hindering not only our happiness but our ability to create meaningful art.

I think we must commit to becoming craftspeople dedicated to the everyday rituals required to hone our craft. This means creating a life where our rituals are sacred and a priority. Dedicate ourselves to understanding our process and seek out strategies to support our process. Whether it’s a few minutes, hours, days or weeks, no matter how strange or weird it seems to others, guard the time required for our practice as sacred.

Our art — and contentment — probably depend on it.