Part five of a disorderly A to Z, to be continued throughout this magazine’s six-issue run.

R is for REJECTION

‘The impulse to trade on essentialist characterisations of culture ought to be rejected, because it is not a monolith. Culture-making is a site of power to transform our collective ways of knowing and relating. It is a creative act wherein exclusions and erasures can easily be perpetuated, and in our roles as artists we have a choice either to be alert or unaware when certain groups are written out of a narrative.’

— Balamohan Shingade, ‘Led astray from a cultural inheritance’, Satellites, 9 August 2024

Aaradhna refusing the award for Best Urban/Hip-Hop Artist at the 2016 New Zealand Vodafone Music Awards: ‘I feel like if you are putting a soul singer next to a hip-hop artist, it’s not fair. I’m a singer, I’m not a rapper, I’m not a hip-hop artist, it feels like I’ve been placed in the category of brown people.’

‘At an artistic level, the 1937 Exhibition represented a fascinating rejection of, but also an implicit enthronement of, European ideals of art and connoisseurship; a somewhat contradictory statement about New Zealand art and nationhood certainly, but a testimony to the multivalency of objects and the narratives woven around them. … The use of Chinese art objects fulfilled the desire of many artists, Beaglehole included, to sever New Zealand’s links with the colonial past and its traditions of British imported art.’

— James Beattie and Lauren Murray, ‘Mapping the social lives of objects: Popular and artistic responses to the 1937 Exhibition of Chinese art in New Zealand’, East Asian History, vol. 37, December 2011

‘Now, I see rejection as a conversation: for every piece that is rejected, at least one other person read it, thought about it, and really considered whether it would be a good fit for publication.’

— Kim Liao, ‘Why you should aim for 100 rejections a year’, Lithub, 28 June 2016

S is for SATIRE

‘Young people are often at the forefront of what I call satirical activism. Satirical activism involves using satire, humor, or humorous formats and genres to voice dissent and evoke collective resistance to the dominant discourse — in the Chinese context, the state-sanctioned discourse. It appears lighthearted in various forms of cynicism and pranking yet it embodies cognitive dissonance, if not changes, in public culture. Satirical activism is youth-led and youth-centered social activism in the era of digital connectivity. From climate change and social justice to political protests, youths have led the charge in using creative means and parody formats to question, mock, and challenge authorities and authoritarianism. What is absurd can be a mechanism for community-building, truth-telling, and surviving censorship.’

— Haiqing Yu, ‘COVID-19, satirical activism, and Chinese youth culture: An introduction’, Global Storytelling: Journal of Digital and Moving Images, vol. 3, no. 2, 2024, p. 1, https://doi.org/10.3998/gs.5303

‘In May 2019, six members of the Peacock Generation (“Daung Doh Myo Sat”) were arrested in Yangon, Myanmar, for performing Thangyat, a Burmese performance art that blends poetic verse with music and comedy. … Satirical in tone, Thangyat provides a forum to express social and political commentary. Public performances were banned by Myanmar’s authorities between 1989 and 2013 because of their critique of the government’s authoritarian rule. In March 2019, authorities in Yangon imposed a requirement for lyrics to be submitted to a government panel for approval.’

— Chris Lin, ‘The case for Myanmar’s Peacock Generation’, Australian Book Review

The First Prime-Time Asian Sitcom by Nahyeon Lee, Silo Theatre, 2022

Photo by David St George

‘Like the Showrunner in Prime-Time, playwright Nahyeon Lee has chosen the sitcom as a vehicle to Trojan horse her audience with big ideas and debates. And like any good Trojan horse, Prime-Time does a convincing job of replicating its vessel. The sitcom within the play is something of an uncanny valley, in that it has all the markers of the real thing yet feels off. Rather than go for crude parody, there is something eerily on point about its construction. Sometimes the best way to critique something broken isn’t to make fun of it, but to honour it and all its flaws, to let its failures and limitations speak for themselves. After all, can satire even pack a punch in a post-Trump world?’

— Nathan Joe, ‘Everyone is a diversity hire’, The Pantograph Punch, 2 November 2022

T is for TASTE

‘In this process, the diasporic artists — in this case, Chinese Australian artists — can at times be agents that initiate changes of taste within the art establishment. However, they are rarely part of the decision-making process … It is true that “diaspora subjects are marked by hybridity and heterogeneity — cultural, linguistic, ethnic, national — and these subjects are defined by a traversal of the boundaries demarcating nation and diaspora.” But it is also true that diasporic Chinese artists can only be considered successful if their artworks can fetch a handsome price on an international market dominated by the West and that their aesthetics are ultimately judged by critics, curators, and collectors from the West.’

— Yiyan Wang, ‘Tyranny of taste: Chinese aesthetics in Australia and on the world stage’, in Diasporic Chineseness after the Rise of China, pp. 149–169

Instagram post by @dietsabya in the midst of a debate about whether NRI (non-resident Indian; aka diaspora) fashion tastes are tacky, which became known as ‘NRI-gate’, 2022

‘The three-year-old mustard green looks gnarled, shrivelled, desaturated. It is the antithesis of how Big (White) Kimchi is sold to you by everyone from Waitrose to Tim Spector: the over saturated, over spiced and fizzy miracle gut cure. … I think, it’s funny how some preserved vegetables are less desirable, never make it onto Instagram tablescapes or magazine editorial spreads. It’s always those vegetables that are overripe and ugly, like the laborious hands or labia of ajummas and ayis. Truth be told, I much prefer eating those over kimchi, like the suān cài I make twice a year in hulking great batches, or the mui choy my great uncle used to preserve on his farm.’

— Jenny Lau, ‘Fermenting a friendship’, Celestial Peach, 23 May 2024

Denise Kum, Saucebox, 1994, mixed media installation. Dunedin Public Art Gallery (20-1997)

‘“Mixed media installation incorporating medical trolleys, glass boxes, lard, soy sauce, Chee Hou sauce, oil, preserved salted duck, duck wings, duck feet and lights.” That list of materials alone gives some sense of how startling it can be to encounter Denise Kum’s Saucebox in a cool white gallery context. Kum exploits the disintegration of materials. The effect of her manipulations of food substances depends, in part, on most viewers’ unfamiliarity with them. This is not the stuff of the Chinese takeaway (although Kum refers to this at times) but a glimpse into the private recesses of the Chinese home kitchen. The alien appearance of materials such as duck feet and duck wings is exaggerated by the fact that Kum encourages them to decay while they are on display, keeping them warm under lamps or in bains-marie so that they moulder, bubble and grow fetid.’

— Dunedin Public Art Gallery, ‘Saucebox’

U is for UTOPIA

‘Cultural Signals was an exhibition and publication produced by architecture students at the University of Auckland in 2004. … The theme of the 2004 exhibition was inspired by Tao-Hua Yuan / Peach Blossom Spring — a Chinese fable about searching for utopia.’

— Cultural Signals in the Satellites archive

Depiction of the Peach Blossom Spring tale on a painting from the Long Corridor, Summer Palace, Beijing, CC BY-SA 3.0

‘Mild spoiler alert: Kā-Shue and Krishnan’s Dairy are not sentimental migrant narratives that demonstrate affability and just-like-you-ness to Pākehā audiences. Both narratives remind us that these characters, these families, do not come from some void, but rather they come from a deep well of cultural history. … In the end, these plays are also sighs of disappointment. They express a sense of our migrant parents’ dreams deferred. The dreams of the land of milk and honey soured.’

— Nathan Joe, ‘Beyond the monolith: In search of representation’, Satellites, 1 October 2024

‘The White Building’s legacy harks back to the Golden Era of the 1960s in Phnom Penh, a time when the arts — including architecture, cinema, dance, music and the visual arts — grew substantially, partially due to state policy.’

— Vera Mey, 'We're in this together', A Year of Conscious Practice, August 2017

The White Building in Phnom Penh, photographed around the time of its inauguration in 1963. National Archives of Cambodia

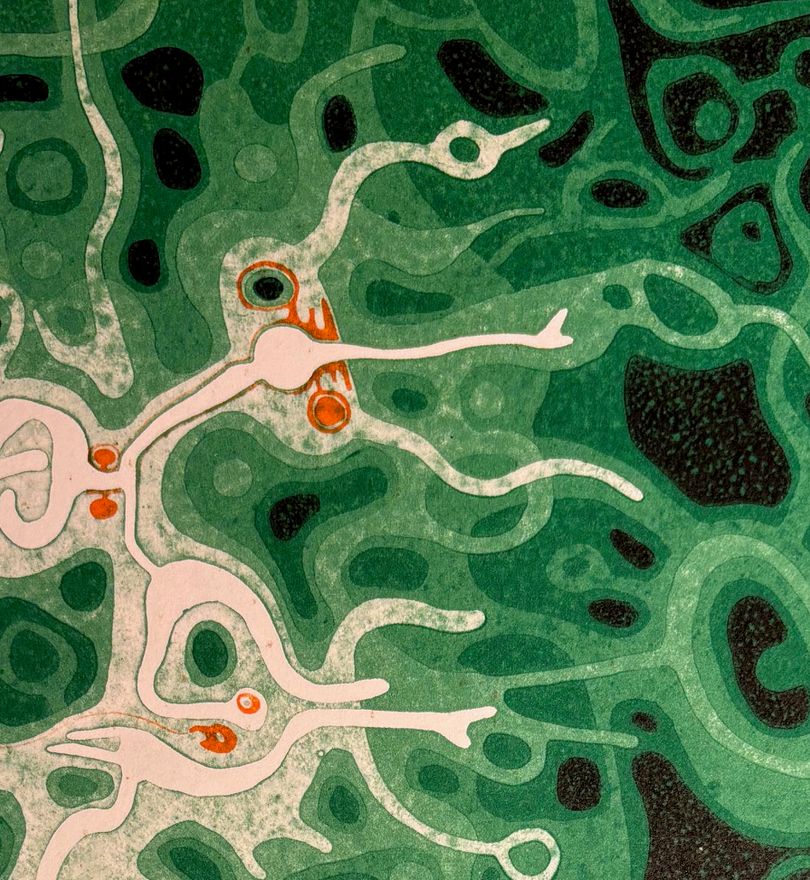

‘Selwyn Muru has described Nin’s interpretation of the land in his work as “forever in a state of change and renewal. Earth and Sky play their own tricks and games. At times eerie light and shadows appear to evoke Hawaiki. Hawaiki of the distant past; Hawaiki in the dimness of time.”’

— Christchurch Art Gallery, Forever Buck Nin

V is for VOICE

‘[Bic] Runga was really into Shanghai lounge diva recordings from the 1930s. “[Mum] had a few tips for me about singing based on the Chinese opera singers she was obsessed with as a child.” Runga has always pulled from both parts of her culture, including the emotive quality in waiata Māori. “It’s all wrapped up in my obsession for Western pop and rock too, so the end result is its own thing.”’

— Karen Hu and Sherry Zhang, ‘9 Kiwi-Asian musicians you should be listening to’, The Pantograph Punch, 2021

error

‘Each narrator was given a unique voice and place on the page. I gave the key Chinese women characters — Ping, and her daughter Cherry — space to tell their own stories, bearing in mind (the history of) settler Chinese women’s tendency to self-efface and “make themselves small” on public platforms. So the poems narrated in Ping’s voice are mostly formatted in short lines and narrow columns that reflect the ways she has learned to minimise her presence in-the-world. Her words are italicised because it’s significant that she has a voice at all. Cherry’s brief asides amidst the omniscient narratives are protected by well-spaced parentheses, and her first-person lyrics offer intimate glimpses into the “inside” Chinese world in a form that has more affinity with the mainstream, thereby bridging the space between them.’

— Grace Yee, ‘5 questions with Grace Yee’, Liminal, 2024

Alice Canton’s documentary theatre work OTHER [chinese], 2017

Photo by Andi Crown

‘In so many ways, “Asian” is a label edged with risk — deployed by others as a reductive categorisation, and most often used by the community as a gesture of solidarity, a mobilising tool, a strategically used identity in response to prejudice, racism, violence. There are tensions within the phrase, too, in terms of who gets to be considered “Asian” and whose voices are privileged in these conversations. Yet there are opportunities for the conversation to move beyond this: to one of what it means to be living in Aotearoa, in one of the most multicultural cities in the world, as Tangata Tiriti. There is an opportunity to articulate a wholly unique lived experience — and, as such, a wholly unique creative voice — distinct from anywhere in Asia, distinct from Asian diaspora voices in other Western contexts, a voice unlike anywhere in the world.’

— Rosabel Tan, Enter the Multiverse: Building a stronger sector for our Asian arts practitioners, Satellites archive, 2022