Before anyone ever typed twitter.com into their address bar, the Aotearoa Ethnic Network helped a whole community find each other. Ruth De Souza, one of AEN’s creators, looks back at what the group achieved, with zero external funding, through the power of an email listserv.

I am writing this looking back. Not only across time but across the ocean. Reflecting on multiculturalism in Aotearoa almost two decades ago, from the unceded lands of Boon wurrung country where I live now. It was a different time. In 2004 we were on the threshold of networked social media that offered opportunities to interact, participate and produce content to counter mass media. Listservs were my bag — the professional kind, like the ones I subscribed to about psychiatric nursing, transcultural nursing, and qualitative research; and the lists that were generative to my cultural identities, such as the Asian Australian list SAWNet, an East African Asians list, and GOA-net. In Aotearoa, the “ethnic” sector was burgeoning demographically and policy wise, but there wasn’t a place where people from thus-designated communities could connect about shared issues, let alone share information.

The installation of a computer terminal at Massey University's Auckland campus library, 2003. Massey University Archives

I started an email list. Andy Willamson, my then partner, did the technical and design things, and I galvanised my extensive ethnic community networks garnered over decades of evening and weekend meetings across Tāmaki Makaurau. I named it the Aotearoa Ethnic Network (AEN), re-appropriating the slightly weird catch-all policy term “ethnic”, developed around that time by the Office of Ethnic Affairs (OEA) to define anyone who didn’t fit into the equally untidy categories of Pākehā, Māori or Pasifika.1 In practical and government terms, this referred to the country’s growing and diverse Asian, Middle Eastern, African and Latin American communities. The term “ethnic”, like any term referring to racialised others, obscures differences in culture, modes of migration, histories, length of settlement and many more things. At the time, most cultural discussions in Aotearoa were framed around biculturalism and te Tiriti o Waitangi, supplemented by Pacific development. There was no multicultural policy and a glacially evolving multicultural infrastructure.

Back in the days when you actually looked forward to an email or two, it was thrilling to see ten arrive daily

Cover of the first issue of the Aotearoa Ethnic Network Journal, 2006

Once we set it up, I told my networks about the email list. I set a few rules about the purpose of the list, and approved folks that joined. When they did so, they could choose to get every email sent in real time, or subscribe to receive a daily digest. I deliberately designed the listserv so that posts within the AEN list could only be made and read by list members, and did not archive it publicly — I thought having this safety measure was important. AEN became a success. People from ethnic communities joined it, but also people from other communities — politicians, policy wonks, activists, academics, media organisations, journalists and more. Back in the days when you actually looked forward to an email or two, it was thrilling to see ten arrive daily, a mélange of announcements of events, recruitment for jobs, and — even more exciting — deep and rich conversations I hadn’t seen anywhere else. The list was also brilliant at self-regulating, despite having upwards of 400 members within a year, which suited me, as I wanted to moderate as little as possible.

The longer form of asynchronous conversations became an aspect that I came to value deeply, and we thought that they deserved a wider audience than the closed group, so Andy and I started an online journal as a way to continue the conversations. What the journal attempted to do was to find the space between mass media, a growing ethnic media and academic writing. The idea was to make it accessible to people who were smart and curious, but to also offer up the opportunity for people who did not get to write publicly to be in conversation with each other.

In the first issue of Aotearoa Ethnic Network Journal, Dave Moskovitz and Anjum Rahman each wrote about Palestine from the point of view of, respectively, a New Zealand Jew and a New Zealand Muslim. Tze Ming Mok and Kumanan Rasanathan provided an edgy and humorous discussion on how ethnic labels can be used strategically to obtain resources, but risk siloing and homogenising groups, in their piece ‘Should we be pushing for a Ministry of Asian Affairs, a Ministry of Ethnic Affairs, or neither?’ International contributions came from UK-based psychiatrist Suman Fernando, discussing racism in the mental health system, and US-based human rights writer Amy West. Māori Party Co-leader Tariana Turia and Mervin Singham, Director of the Office of Ethnic Affairs, also contributed.

Diversity Action Programme badge, printed in the Aotearoa Ethnic Network Journal, 2006

The first issue of AEN Journal was launched by then Race Relations Commissioner Joris de Bres, on behalf of their Diversity Action Programme, at the Human Rights Commission’s Tāmaki Makaurau office on Monday 3 July 2006. The Diversity Action Programme, an annual forum and awards, emerged in response to the desecration of Jewish graves in Te Whanganui-a-Tara in 2004. Organisations or groups that signed up to the programme committed to delivering an event or programme that would contribute to “diversity”. What was powerful about this programme was that it was not passive — organisations had to nominate tangible projects annually to remain in it. This active participation made it feel like many groups were taking anti-racist actions in their communities (professional and geographical), and that these combined and collective events could counter broader injustices. The work of this powerful programme was amplified through a weekly newsletter that shared news of the projects.

In a guest editorial in the first issue, de Bres said: ‘the Aotearoa Ethnic Network has already made an important contribution to on-line debate and dialogue, as well as being a lively market for information exchange.’ He suggested that AEN Journal ‘adds to that contribution significantly by providing a forum for more substantial and considered discussion of the issues.’ In the second issue we focused on the theme of creativity and the arts; the third on information technology and ethnic communities; and in the final issue I chose the theme of religion and spirituality. Andy Willamson designed the first three issues and in the fourth I was assisted by FitzBeck consulting , who produced a beautiful cover. We received an acknowledgement from the Diversity Action Programme for contributing to race relations in 2005 and 2006, culminating in an Award for Outstanding Contribution to Race Relations in 2007.

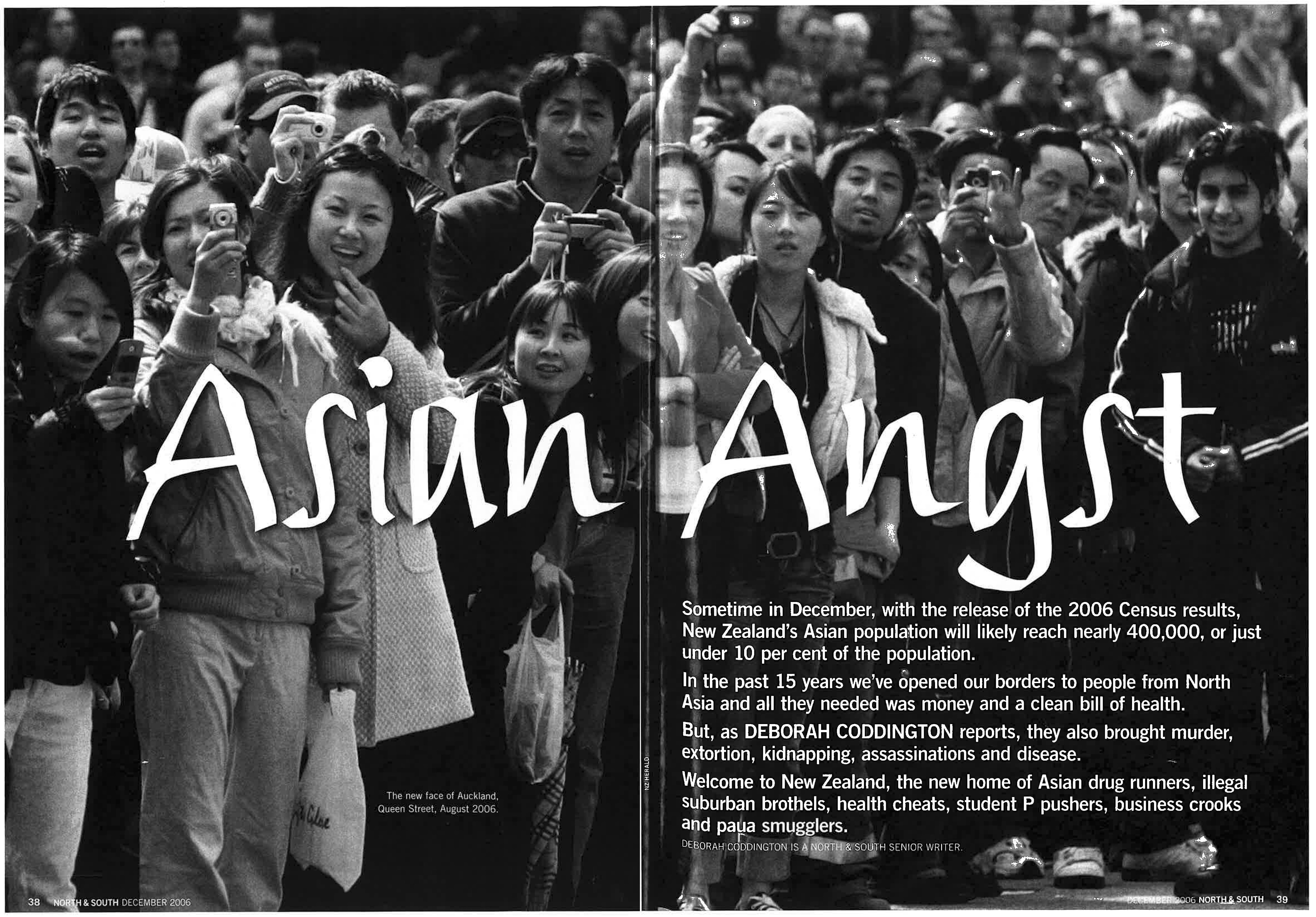

Deborah Coddington, 'Asian Angst', North & South, December 2006

The listserv also connected people to address issues of social change and justice. One memorable example was when Tze Ming Mok (a staunch member and supporter, also featured in this issue) asked members if we wanted to respond in some way to a dreadful article in North & South magazine by journalist Deborah Coddington, which represented Chinese immigrants as responsible for ‘a rising crime tide’. The Press Council later ruled the piece as inaccurate and discriminatory. Following robust discussion on AEN, we also managed to have headlines and representations changed in the media. In one instance, AEN members expressed concerns about the description of a man shot in Iraq as a ‘New Zealand passport holder’ rather than a ‘New Zealander’. The headline was changed soon after and the Human Rights Commission followed up with an investigation in 2008.

I still feel a great deal of pride for what we achieved without ever being funded by anybody, and for being well ahead of the curve.

In 2007 I was struggling with juggling the journal, full-time work and a PhD. I put out one final journal issue and I continued to run the email list. In 2013, after completing my PhD, I couldn’t find work locally and moved to Australia. There, I continued to moderate and run AEN, but was conscious I no longer lived in Aotearoa. I approached several organisations about continuing to run it but there were no takers, possibly because the era of lower-effort social media networking was now in full swing.

I wound up the listserv in 2020, after sixteen years. Now there are numerous other ways for people to connect, but I still feel a great deal of pride for what we achieved without ever being funded by anybody, and for being well ahead of the curve. I did try recreating the list on social media, but, as Farhad Manjoo has pointed out, there is something quite different about moving the rich discussions of a listserv group to social media such as Facebook.2 Despite the reach of these platforms, the depth and interest of these conversations does not compare to listservs, whether this is due to the intimacy and security of a small, closed, members-only, special-interest group, or because, on a practical level, emails allow for long messages without character limits, allowing for drafting, editing and formatting links, etc. It may also be because email lists are specifically about discussing things. Whereas today’s social networks serve personalised content guided by individualised algorithms and a user’s one-to-one relationships, the listserv drew members in for a shared purpose.

Looking back now makes me reflect on whether what we thought of as liberating online technological practices have actually translated into visible social movements.3 It feels as though the AEN listserv, in common with others, lost something in the hyper-visual, accelerated world of likes and hearts through platforms such as Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.

At the time, the list provided a temporary respite from an unrelenting monocultural mediascape. AEN filled a niche for Aotearoa ethnic minorities and, in its classic email listserv format, sat somewhere between (in today’s terms) the networking potential of peak-era Facebook and the professional impact of LinkedIn, but with the depth and intimacy of a group-email chain. We were able to facilitate multicultural and intercultural dialogues, without centring the white subject. In a time of ethnic communities as “others”, members could be not simply consumers of knowledge, but producers of knowledge, and speak for ourselves in a public sphere of our own for the first time — a wonderful place of community and support.