Over the past few decades, Asian artists in Aotearoa have circled the same questions: what is our history? And how do we belong? Emma Ng considers some possible answers.

There are artworks I’ve only read about, or seen poor images of, that are now just faint memory blips. It’s hard to salvage even my second-hand memories of them: Which book did I see that in? What keywords can I type into Google to reel that artwork out of the depths? If there’s nothing on the internet … then what?

Here are the two things I remember about one slippery work:

- It was displayed in the office tower in the Auckland CBD that looks like a red pagoda;1

- It was by the artist Yuk King Tan, fresh out of art school in the early 1990s when she’d already, in the words of fellow artist Tessa Laird, painted the town red.2

I was born in 1990, and lots from that decade never made it onto the internet. The internet is so bright and all-consuming that it eclipses the hard-copy books, newspaper clippings and photographs that are still out there. Now that it’s in shadow, this ephemera seems harder to find. When I try to recall the photographs I saw of this particular artwork, I can’t quite bring them into focus in my mind’s eye. But their fuzzy memory still blinks faintly at me, as if signalling from the deep.3

Maybe those photographs were my first encounter with Yuk King’s practice, taking place around the time I began working as a curator, ten years ago. By then, she had been overseas for almost as long. But her signs remained, and I think the traces of her wild early success appealed to my quiet desire for us to have a history; for there to be a lineage of Asian artists woven through this country’s artist-run spaces and galleries; and to know that they were at the party, which, in the 1990s, they were.

I think the traces of her wild early success appealed to my quiet desire for us to have a history

Today, I know there are plenty of artists and curators (many younger than me) who share this impulse, searching for artworks, moments and artists to build their practices in relation with. Surfacing again and again throughout the work of Asian visual artists in Aotearoa is a search for ways to belong. And beneath the changing tides of Aotearoa Asian art is an ancient undercurrent: the desire to feel at home.4

Moved by such impulses, it’s easy to find ourselves reaching towards the promise of multiculturalism, our hands grasping for a politics of recognition. But as I’ve asked elsewhere, ‘How can we belong here, become “from here”, without re-enacting the violence that is historically embedded in the gesture of trying to belong?’ As Asian artists and people, we have played many different roles in settling and unsettling this place. ‘Diversity discourse in Aotearoa must be understood in the context of the colonial project to eliminate and dispossess Māori,’ write researchers Arama Rata (Ngāti Maniapoto, Taranaki, Ngāruahine) and Faisal Al-Asaad (tauiwi, Iraq). What has amplified among Asian artists in recent decades (and outside of the arts, too) is a self-conscious search for the right ways to belong — and maybe a changing answer about what exactly it is that Aotearoa Asian artists are trying to belong to.

Surfaced here are artists and artworks that offer a range of possibilities for ways of being, beneath the broad umbrella of Aotearoa Asian identification. We’ll look back beyond the 90s, all the way to the other end of the century, bringing together artists who had, and have, their own conceptions of who they were creating work in relation with. This is an attempt to formulate an art history, but it is selective — unfolding thematically and focusing on a few ideas that I think are interesting and fundamental, if we are to form an art history that can take us somewhere new.

William Gee, carved scene, circa 1905. Te Papa (GH007416) (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

I. TARANAKI, SOMETIME AROUND 1905

Te Papa is an iceberg. Most of the collections are not on display but kept below the surface. I’ve worked at the museum for five years, and one perk is getting to see some deep-freeze treasures. In 2021, during an event with Migrant Zine Collective, Grace Gassin, Curator Asian New Zealand Histories, showed us a tōtara carving made sometime around 1905. The carving is like a miniature theatre set. Snow-capped Taranaki rises in the background, while water flows toward a wharenui and mirror-glass river in the foreground. The craftsmanship is simple; the wood unadorned except for flecks of pāua inlay and touches of white paint. But despite its charm, this is an awkward object. The carving of the meeting house is clumsy. It’s clear that this is the work of settler hands, rather than the whakairo of a Māori carver — the work of an outsider who has seen the swirling forms of maihi and tekoteko but does not understand them as taonga tuku iho.5

Those settler hands belonged to William Gee, born in Canton, China, in 1832. After arriving in New Zealand in his mid-thirties, Gee (also known as Ah Gee and Sam Wah) set up in colonial Wellington as a wood and stone carver.6 He was often commissioned to create ornamental fittings for homes and churches (and on at least one occasion, a street-spanning archway for a royal visit).

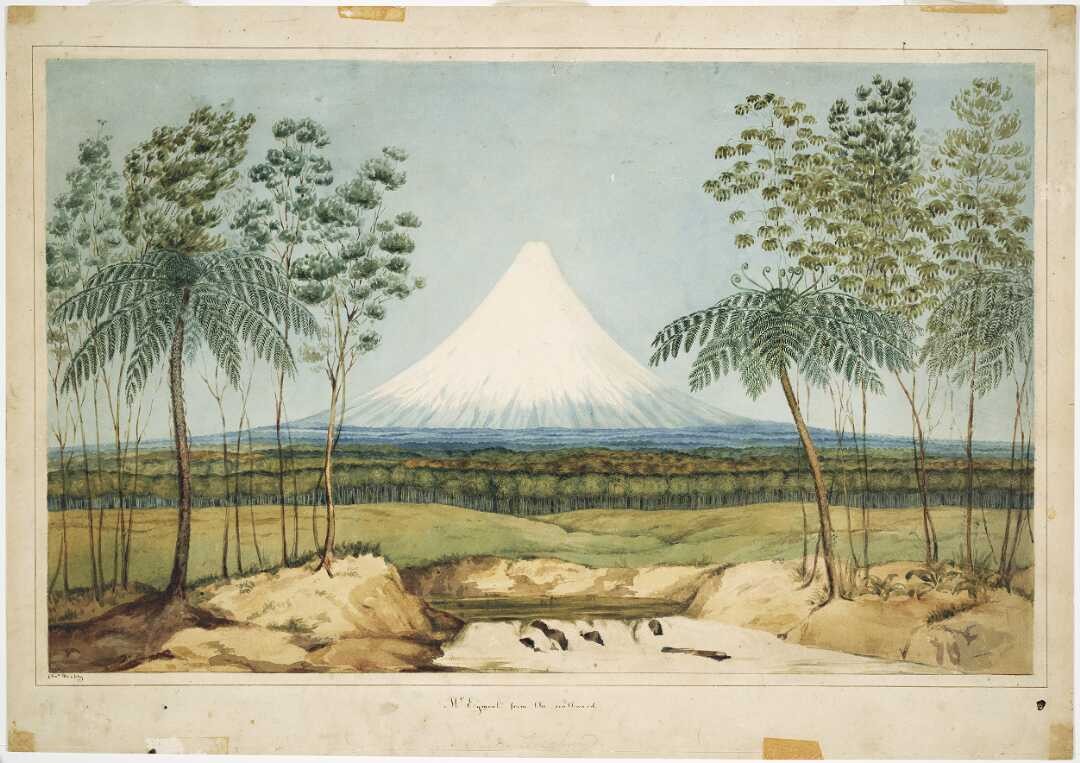

Charles Heaphy, Mt Egmont from the southward, 1840. Alexander Turnbull Library (C-025-008)

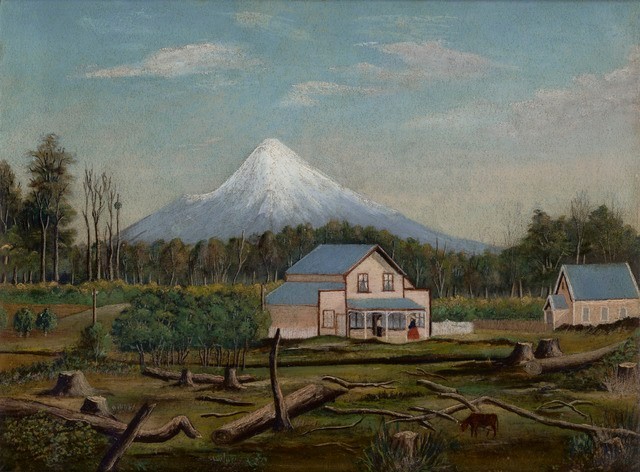

This carving is part of the history collections at Te Papa,7 but when we bring it into proximity with New Zealand Art (with a capital A) it begins to speak. First, it enters into dialogue with other settler art from the colonial period: the ponga trees framing the scene and the steep mountain slopes recall Mt Egmont from the southward, painted by Charles Heaphy in 1840; or perhaps the choice of vantage point, with the mountain’s little bump, has something in common with the Messenger Sisters’ Landscape with settlers from 1857.8

But these comparisons also reveal differences. Heaphy clears the land for settlement. His work is explicitly colonial: produced for The New Zealand Company and published in England as an advertisement to potential settlers. The Messenger Sisters complete the vision by adding a homestead to the naked expanse of cleared land. By contrast, there’s no empty space waiting to be filled in Ah Gee’s carving. Instead there’s a strong connection between mountain, river, bush and — most notably — the people who already occupy the land. On close viewing, there are many small figures standing, sitting and working around the wharenui. Gee’s composition harmonises busy hapū life within te taiao, the natural world.

Messenger Sisters, Landscape with settlers, about 1857. Te Papa (1999-0003-1)

In this way, the carving anticipates more recent Taranaki works by tauiwi artists sensitive to violent and unsettled landscape histories. Printmaker Marian Maguire revisits Heaphy’s Taranaki repeatedly throughout her work, drawing our attention to landscapes as artistic constructions imbued with political agendas. Balamohan Shingade (then artist-curator, now researcher) approached the maunga another way. In 2012, quoting Hokusai’s Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji, he invited thirty-six artists, curators and makers to journey to Taranaki together before creating responses that were exhibited at the Govett-Brewster ‘as a trace of the journey and encounter’.9 Writing later about the irreconcilable modes of tourism and pilgrimage invoked in Thirty-six Views of Mount Taranaki, Balamohan suggests that both are perhaps still their own kind of imposition upon the whenua.

We could continue to tease out this network of artistic visions, but my aim, in opening with this carving, is simply to hint at the connections waiting to be made among the artworks and objects that are still with us. One version of art historical reappraisal would see us ornamenting the margins, using Asian artists and works to embellish already established histories. Ah Gee shows us there’s more to be offered if we give the shelves a good rattle — in the hope that ideas that we didn’t already know were there might fall out.

II. A QUICK SKETCH OF THE OUTLINES

Through his son Billy, William Gee is directly connected to one of our first and most well-known Aotearoa Asian artists, Guy Ngan. As a cabinetmaker in Wellington, Gee the Younger taught a teenage Ngan to make furniture and carve wood — activities the artist continued throughout his long career. Ngan worked in a largely modernist mode from the 1950s onwards, completing a sizeable number of public art commissions in addition to producing paintings and furniture, and designing and building a home for his family in Stokes Valley.

As the 1960s and 70s progressed, other Asian artists began working in mainstream visual arts contexts, such as Buck Nin (aka Buck Loy Nin; Ngāti Raukawa, Ngāti Toa), Brent Wong and Parbhu Makan. They are all Chinese or Indian New Zealanders, reflecting immigration patterns to that point, which were shaped by restrictive legislation through most of the 20th century and what amounted, in practice, to a ‘White New Zealand’ policy. Nin was a student of the Tovey generation, and helped shape the emerging contemporary Māori art movement. Wong became known for his enigmatic paintings of landscapes shadowed by floating fragments of heavy architecture, while Makan practised a fledgling mode of social documentary photography and was part of the performance and new media scene around Jim Allen at Elam School of Fine Arts. These artists are too few in number, and their interests and modes of working too diverse to be grouped together as a movement, but they were active figures in the country’s developing art institutions — exhibiting, winning commissions, creating work acquired for major collections, and even helming galleries.

Feature on Denise Kum, MORE magazine, November 1994, p. 116

Michele Hewitson, 'Through the looking glass', NZ Herald, December 12, 1997 & Tessa Laird, 'Museum misses chance to change', NZ Herald, January 8, 1998

In the 1990s a new generation of art school graduates burned brightly. Artists such as Yuk King Tan, Shruti Yatri, Denise Kum, Haruhiko (Haru) Sameshima, Simon Kaan (Ngāi Tahu) and Luise Fong were frequently included in exhibitions — Denise and Luise were even among a group described by Justin Paton as ‘curators’ pets’ — and were part of an energetic swirl of artist-run spaces around the turn of the millennium. Some of these artists and the curators they worked with foregrounded issues of cultural identity, as playwrights Jacob Rajan and Lynda Chanwai-Earle were doing in local theatre at the same time. For example, Denise made sculptures with festering lotus leaves, duck and soy sauce, while Yuk manipulated cultural icons such as fireworks and red tassels, paper fans and Chinese lanterns.

At the time, curator Richard Dale described Yuk and Denise as employing ‘post-orientalist’ strategies (interestingly, grouping them with non-Asian artists appropriating Asian motifs, such as Daniel Malone).10 Suggesting that these strategies wielded a threatening edge in turn-of-the-millennium Aotearoa, Dale discusses the exhibition The Oriental Room, curated by artist Jacob Faull. In 1997 a group of contemporary artists, including Yuk and Daniel Malone, were invited to display work in Auckland War Memorial Museum’s Asian Hall, with many choosing to address ‘orientalist concerns in a critical fashion.’ The museum closed the exhibition early, citing negative public feedback and divergence from their ‘core activities’11 — a decision seen by many as symptomatic of a sluggishly monocultural institutional landscape.

These artists were responding to a rapidly changing society. Wholesale revision of New Zealand’s immigration criteria at the end of the 1980s had removed the preference for migrants from certain ethnic and national backgrounds (largely British and Northern European). This allowed Asian migration to increase, resulting in backlash against Asian residents (both new and established), and it’s in this context that these artists were renegotiating New Zealand’s cultural landscape.

Installation images of Seung Yul Oh: Moamoa a Decade, City Gallery Wellington, 2014

These legislative changes also enabled the arrival of immigrants from a greater variety of Asian nations. By the mid-2000s, artists who had moved to New Zealand as children or young people (the 1.5 generation), from countries such as South Korea and Malaysia, began to graduate from the country’s art schools — among them now well-known names such as Hye Rim Lee, Seung Yul Oh, Jae Hoon Lee and Liyen Chong. These art school graduates had a sophisticated grasp of the lingua franca of contemporary art practice, and their work circulated in dealer galleries and public-run institutions around Aotearoa. The work of these artists was informed by their cultural identities but was not often “about” marginalisation and belonging.

Seung Yul Oh’s ambitious and playful installations — inflatable structures that filled entire rooms, which visitors could crawl through, and self-balancing eggs that could be tipped over — were particularly popular among the big public galleries. Within a decade of Oh graduating from art school, Dunedin Public Art Gallery and City Gallery Wellington staged a survey of his work. At the same time, contemporary art networks in Asia were developing apace, with many art spaces and biennales established in a short space of time. Perhaps because they maintained transnational links — or perhaps because diaspora anxieties were not front and centre in their work — many of these artists enjoyed a high level of international mobility, moving between Aotearoa and other art scenes to live and work.

During the 2010s, the “social turn” observed in international art practice also found form in Aotearoa. Between them, third-generation Cantonese New Zealand artist Kerry Ann Lee and Tiffany Singh, who has Indo-Fijian, Pākehā and Sāmoan heritage, illustrate different approaches to community-engaged art practice. Singh’s installation Knock On The Sky Listen To The Sound (2012), created for the 18th Biennale of Sydney, encouraged visitors to touch the work, activating its ribbons and chimes, and inviting them to reflect on their own belief systems while they were immersed in its colour and sound. Singh has since developed a social impact framework around her art practice, seeking to create art experiences that foster social cohesion.

Taking a slightly different tack, Kerry Ann Lee has long incorporated community-oriented practice into her work as an artist, designer, zine-maker and educator. As well as exhibiting collage and installation works in galleries, Kerry Ann has facilitated projects that collate knowledge held by communities through free public workshops and activities such as zine-making, drawing and podcasting. Building community among Asian artists is another thread that runs through her practice. She has participated in various iterations of Asian artist gatherings, including the 2013 Chinese New Zealand Artists Hui, which (along with a 2017 hui organised by Amy Weng) can be seen as a precursor to the month-long 2018 Asian Aotearoa Arts Hui, of which Kerry Ann was Creative Director.

Asian Aotearoa Arts Hui, opening party at Te Papa, September 2018

Photos by Jo Moore, Te Papa

Kerry Ann describes the 2018 hui in Pōneke as ‘the mega hui’ and it was an important nexus for Aotearoa Asian arts, with artists and arts workers of different ages, art forms and ethnicities coming together at scale. I had recently returned to Aotearoa and helped organise the opening party for the hui, which about 1500 people attended at Te Papa. Attending the hui were some of the artists already mentioned — Simon Kaan, Yuk King Tan, Luise Fong and Kerry Ann Lee — alongside a new generation of artists who had emerged over the last decade. Although it was noted that the hui still reflected ongoing biases towards east-Asian (particularly Chinese) perspectives and practices, within this new cohort there was a huge range of immigration experiences, family connections to different parts of Asia, and ways of working. Also attending the hui were scholars, curators and writers: people like Vera Mey, Yiyan Wang, Balamohan Shingade, Amy Weng and myself — and many more who have begun this work since.

Artworks do not exist in a vacuum, and the latter group are active participants in systems of contemporary art presentation and interpretation. Alongside artists, these supporting figures can be collaborators and accomplices, framing artworks with their own intentions and ushering in shifts and trends. Through the 2010s, the tandem swerves of artists and curators saw another shift gather momentum, as Asian artists have increasingly been positioned within an “Asia–Pacific” framework.

This framework takes the geo-political conceit and turns it inwards, reinventing it as a relation of solidarity that allows the works of Asian, Māori and Moana Oceania artists to sit alongside each other. It builds on impulses that were already there in the work of artists such as Yuk King Tan and curators like Anna-Marie White,12 but has been reinvigorated by the work of an emerging generation of Māori, Moana Oceania and Asian curators and artist-curators. Responding to the collective search among tauiwi artists for ways to ‘become from here’, this shift is sensitive to tangata whenua indigeneity — building concentric circles outwards from Māori indigeneity to the regional indigeneity of their whanaunga in Polynesia and wider Moana Oceania with the hope that perhaps, just perhaps, these ripples of whanaungatanga might extend as far as Asia via islands such as Taiwan and the Philippines.

Guy Ngan, woodcarving blurb featuring many of his anchor stone-inspired sculptures, 2003

Ngan family

III. IDENTITY IN MOTION

Isolation was one of the founding narratives of settler New Zealand art history. It allowed art historians to slough away certain influences in the service of a burgeoning national identity produced instead by qualities perceived to be essential to this place. This was the bedrock of New Zealand art history until the final quarter of the 20th century when, as the country’s self-conception was split apart and remade, so too the national art history was eroded, chipped away and reformed. At the same time, the ‘antagonism between nationalism and internationalism’ that dominated the 1970s and 80s was still dependent on the isolation narrative of the preceding generation — in that it allowed a younger cohort to “re-enter” the world at large to participate in global circulations of contemporary art.13

Asian artists do not fit easily within these frames. They are, in many ways, incompatible with art histories that depend on isolation because they have always been connected, moving, radicant.14 Diaspora stories often reveal a highly connected world rather than support the idea of remote islands in which only privileged ideas are able to pass in or out.

Guy Ngan, born in 1926, was cosmopolitan. He completed some of his education in China and some in Wellington, then later studied art in London, at Goldsmiths and the Royal College of Art, where he met English artists he admired such as Barbara Hepworth and Henry Moore. He schooled himself in the cultural output of both Chinese and Western civilisations, and took interest in the Pacific art traditions he saw around him. He travelled, spending time in Rome, North America and Scandinavia.

At the same time, Ngan was proudly Cantonese, and through his work he searched for ways to position himself as a Chinese citizen of the Pacific — fixing upon migratory symbols such as Kupe’s anchor stone, which inspired his own series of “anchor forms”. Writing in 2006, curator Heather Galbraith described Ngan’s interest in the migratory routes of Polynesian peoples from South China over tens of thousands of years. Ngan also fixated on the ‘three-fingered Tiki Hand’ found in whakairo, for its ‘similarity with the three front claws of a bird, potentially pointing to the reliance of early navigators on sea birds for wayfaring.’15 He produced scores of paintings that explored this motif. These works were part of his own homing sensibility.

As part of the development of a robust art history, we must acknowledge that Ngan’s boundless curiosity produced moments of cultural appropriation akin to those that saw contemporaries such as Gordon Walters roundly criticised. But unlike Walters, who drip-fed only works that he considered fully refined, Ngan was unafraid to show his working, even publishing a “scrapbook” (2010, with the architect Ron Sang). Ngan’s openness around his process allows us to better understand his intentions in making these works, without excusing the appropriation itself. His desire was to make connections and draw attention to cultural commonalities, rather than to displace, obscure, or “improve” on Māori art.

Other related changes were reshaping Aotearoa through the late 20th century: the development of (sometimes factious and fractious) contemporary Māori art movements,16 strengthening Māori political movements, and the gradual assimilation of bicultural ideas into state institutions and the public sector.17 Writing about Guy Ngan in 2019, I suggested that one possible factor that contributed to his exclusion from the grand narratives of New Zealand art history is that the nuances of his self-identity could not easily be digested by an art world already struggling to negotiate these contested political and cultural questions arising between Māori and Pākehā from the 1970s onwards.18

We’re using the ‘established mainstream art criteria’ of settler New Zealand to assert Ngan’s perceived exclusion here, and Ngan himself was indeed sometimes disappointed by a lack of interest from the art establishment.19 But he did leave something for us, to land in our hands when we rattle those shelves, something to help us look towards the future that was yet to come. Through artworks such as the anchor forms, he sought to establish relations between Chinese, Māori and Pacific peoples — directly and without Pākehā mediation (although certainly not free of the influence of English artists such as Hepworth and Moore!). In this there is an intimacy between the desires Ngan expressed through his art practice, and the desire to build relations between these groups that continues to motivate artists today.

A spread from Haruhiko Sameshima, 'The Shopping Mall as a Place of Contemplation – a photo story', in New Zealand By the Way - Immigrant Photographers & Photographs of Immigrants, 1996

Courtesy of Haruhiko Sameshima

Haruhiko Sameshima, Athenes, 1992

Courtesy of Haruhiko Sameshima

The work of photographer and publisher Haru Sameshima is distinct from Ngan’s in almost every way, reflecting their generational differences. Haru, thirty years younger than Guy Ngan, displays a postmodern impulse to collect and mix found images with his own, and even the most vernacular of subjects — crates of catch on a fishing boat and billboards over empty carparks — make it into his photographs. Born in 1958 in Shizuoka, Japan, Haru has described the terms of his first engagement with New Zealand:

When my father made his first trip to New Zealand in the late 1960s, he returned with a collection of photographs he had taken, and picture books he had purchased, to show us what the place was like. Picture postcards and scenic publications, and his own photographs of the travels were my first impression of this country that would become my home.20

So began the impulse that has continued to govern Haru’s exploration of the world: he seeks to understand it through images. I enjoy looking at and thinking about his photograph Athenes. Taken in a museum in Greece in 1992, it could, on the one hand, simply be described as a photograph taken by a New Zealander on their OE (as it is on Te Papa’s website). But what is the “overseas experience” to an artist for whom there is no simple binary relationship between “New Zealand” and “overseas”?

For this radicant artist, whose life has been profoundly shaped by the power of images from a young age, there is no naïve encounter between artist and what they see around them. Curator Athol McCredie has written, ‘Athenes is therefore not about Greece at all, but about the ways in which cultures can be subjected to the forces represented by the museum — an international institution that smooths cultural difference and packages it for easy consumption.’ Whereas the regionalists sought to translate the hard New Zealand light they perceived directly into paint, Haru’s work is indirect, capturing a view only through refracted light and shadow. He draws our attention to the way that, at every turn, our encounters are mediated by culture, context and our own subjectivity.

Li-Ming Hu, Where is the art? (installation view) in Elsewhere and nowhere else, Te Tuhi, 2022

Photo by Sam Hartnett

And how do we account for Asian artists who have since left this diaspora? Yuk King Tan is a key figure in Aotearoa Asian art — yet she was born in Australia, spent some of her childhood in Malaysia and the United States, and has lived in Hong Kong for almost two decades now. However, she maintains familial links with Aotearoa, and continues to exhibit new work here — including work that engages with the struggle for democracy in Hong Kong. What are the relations invoked in such artworks? What is their function when they are shown in Aotearoa, rather than in Hong Kong?

A recent exhibition curated by Vera Mey (also now living overseas) pushed questions like these to the fore. Elsewhere and nowhere else featured the work of ‘three artists who are umbilically connected to Aotearoa but for different reasons — live elsewhere’: Yuk King Tan, Kah Bee Chow and Li-Ming Hu. Since the early 2010s, when she was the Assistant Director at ST PAUL St Gallery, Vera has tried to draw our attention to the wider Asia–Pacific context that Aotearoa sits within, eventually leaving here in 2014, frustrated by an ongoing reluctance to connect with these international contexts. With Elsewhere and nowhere else Mey continued to refuse simplistic expectations of Aotearoa Asian artists — choosing not to use the word “Asian” in any of the exhibition materials, and writing ‘What binds the artists in this exhibition together is everything and nothing.’

Mey’s seemingly paradoxical statement reminds us that one of the challenges we face is the absolute impossibility of ever trying to define or understand “Asia” (or Asian New Zealand-ness) as something cohesive — or even useful. As literary theorist Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak has suggested, ‘the problem of desire for Asianism in Asians [is] something to unlearn and relearn imaginatively.’21 The lives and artistic practices of Guy Ngan, Haru Sameshima, Yuk King Tan and Vera Mey show us how the door swings open when we embrace this challenge.

IV. IS “ASIA” IN THE ROOM WITH US RIGHT NOW?

Established in 1994 as the Asia 2000 Foundation, the Asia New Zealand Foundation promotes engagement with Asia’s economies, partly by deepening understanding of Asia among New Zealanders. Throughout their history, they have funded opportunities for New Zealand artists to undertake residencies at art spaces in Asia, as well as sponsoring many curators to travel to Asia. I took part in a curators’ tour in 2015, visiting China and Japan with fellow curators Abby Cunnane and Lara Strongman, and our trip was a whirlwind of artists’ studios and art spaces: a guided exposure to, and experience of, Asia’s art scenes and subscenes that neither I, nor my workplace, could’ve organised or funded independently.

Anna Sanderson, 'futures trading', monica, Summer 1997

The Foundation’s ultimately soft-diplomatic and economic aims have, at times, sat awkwardly alongside their generous sponsorship of arts activities. In 1997 Anna Sanderson observed in monica magazine that this produced a fusion ‘between left and right-wing ideas about art and politics’.22 As an illustration of this ideological dovetailing, she quotes Auckland Art Gallery Director Chris Saines writing for the Asia 2000 Foundation: 'with cultural understanding comes tolerance and with tolerance greater understanding of “ways of doing” and therefore, concomitant insight into what powers and motivates people as a market.' Almost twenty years later, in her introduction to the Imagine Asia catalogue, Vera Mey echoed the tensions identified by Sanderson: 'To be an active contributor to this conversation in the “Asian Century” it is essential we develop a greater depth of understanding than simply seeing Asia as “other” or as a source of economic benefit. Understanding Asia from a cultural perspective allows for more meaningful engagement at a creative and human level.'

error

On the one hand, Aotearoa art institutions have embraced contemporary art from Asia, perhaps encouraged by this general promotion of Asia in this country over the last thirty years. During 2009–10, the Govett-Brewster, which has always sought to position itself as a hub for ‘contemporary art of the Pacific Rim’, staged a year-long series of exhibitions by mainland Chinese artists. Other Govett-Brewster shows of art from Asia included Mediarena: Contemporary Art From Japan (2004), Activating Korea: Tides of Collective Action (2007) and Sub-Topical Heat: New art from South Asia (2012). Elsewhere, Dunedin Public Art Gallery has staged New Networks: Contemporary Chinese Art (2018–19), City Gallery Wellington featured Cao Fei: #18 (2018–19), Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki produced an interactive work by Yayoi Kusama (2017–18), and showed Lee Mingwei and His Relations: The Art of Participation (2016–17) and Yang Fudong: Filmscapes (2015–16). At the country’s smaller public galleries and art spaces, contemporary Asian art was also being shown. The Dowse exhibited Liu Jianhua: Transfer (2016), The Physics Room toured To Voice 發聲 Introducing Hong Kong’s Umbrella Movement (2015–16), and Te Tuhi developed the Art and Social Change Research Project: Delhi Residency (2014), which was also shown at The Physics Room.

Michael Lin and Atelier Bow Wow (with Andrew Barrie), Model Home in the 5th Auckland Triennial, Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, 2012

I sometimes wonder whether this high level of engagement with contemporary art from Asia — in part thanks to activities like sending (mostly Pākehā) artists and curators offshore for residencies and tours — has promoted the idea that “Asian” art is international art. For the 5th Auckland Triennal, Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki engaged influential Chinese curator Hou Hanru and the resulting triennial featured a number of contemporary Asian artists: Ho Tzu Nyen, Michael Lin, Atelier Bow-Wow, Zhou Tao, Ou Ning and the Bishan Commune, Do Ho Suh, Shahzia Sikander, Bijoy Jain of Studio Mumbai, and Ryoji Ikeda. The exhibition was impressive for Hou’s engagement with Aotearoa artists and local political and ecological issues, which he brought into conversation with the visiting artists and works. But despite this, the programme was light on local Asian artists. None were included, except through the architecture and design programme.

What’s missing is the puzzle piece that allows local Asian art practices to be seen as both Asian and of Aotearoa. I was recently asked to consider the exhibition history of Te Tuhi, in Pakuranga, as one of the contributors to their fiftieth anniversary book. Throughout their 2012–20 programme, they had a strong record of showing international Asian artists alongside Aotearoa artists, as in Hou’s triennial. They also frequently presented solo exhibitions by local Asian artists such as Yona Lee, Bepen Bhana and Hikalu Clarke. But these two modes did not overlap much and, as with the Triennial, the ambitious international group exhibitions rarely included local Asian artists. Perhaps local Asian artists weren’t instinctively seen as envoys of an “Aotearoa” voice.

I sometimes wonder whether this has promoted the idea that “Asian” art is international art.

These are observations that can only be made by slicing into monolithic ideas of what Asia or Asian art are, allowing us to draw distinctions between Asian art made in Aotearoa, Asian art made in Asia, and Asian art made in other parts of the diaspora. It’s a reminder to keep slicing, to help us examine our other biases (biggest of all, Asia ≠ China). It’s also a reminder to expand our field of vision beyond individual artworks to consider how they are exhibited and framed.

Working at Te Papa, I noticed that the museum has devoted significant resource and floor space to local Asian artists over the years. These commissions and solo showings include Return to Skyland (2018–19) and Knowledge on a beam of starlight (2014–16) by Kerry Ann Lee, Indra’s bow (2018–22) and Total internal reflection (2018–22) by Tiffany Singh, Movement image time (2018–21) by Jeena Shin, Oddooki (2008–9) by Seung Yul Oh, and the display of Yuk King Tan’s The New Temple – I give so that you may give, I give so that you may go and stay away (2018). Yet I also noticed that in all of these instances, the works were separated spatially from other works (oftentimes due to their scale): installed in stairways, on outdoor terraces, and in galleries on their own.

At first this might seem wholly positive — an affirmation that Aotearoa Asian artists can hold their own, and are worthy of the spotlight. But it also produces a kind of spatial “othering” because it isn’t paired with consistent inclusion of local Asian artists in group exhibitions — the big thematic shows that use art to “think through” who we are in Aotearoa. In this regard, small artworks — ones that can be integrated into constellations of meaning, alongside other works — are important too. The exhibition Hiahia Whenua / Landscape and Desire, which opened in 2023, ‘explores the different ways that artists in Aotearoa have expressed their relationship to the land’. It features works by Māori and Pākehā artists, including the Messenger Sisters’ Landscape with settlers. This would have been a great opportunity to show William Gee's carving, moving the exhibition beyond being bicultural in the Māori–Pākehā sense to explore more expansive tangata whenua–tangata tiriti relations.

Emerging Curators programme participants and mentors at Aoraki Mt Cook, November 2015

V. FINDING WAYS IN

In 2009 Anna-Marie White (Te Ātiawa) curated an exhibition called The Maui Dynasty at the Suter Art Gallery in Whakatū Nelson, which took its cues from the same Asian–Polynesian migratory connections that interested Guy Ngan. ‘The Asian origin of Polynesian cultures is a well-documented but suspiciously under-celebrated theory,’ Anna-Marie told the Nelson Mail in 2009. ‘By taking this theory seriously, this exhibition argues that New Zealand art is a contemporary manifestation of this ancient cultural lineage.’ Anna-Marie spotlit Māori, Pacific and Asian influences in contemporary New Zealand art, through works by John Edgar, Max Gimblett, Janet Green, Brett Graham, Niki Hastings-McFall, Jae Hoon Lee, Simon Kaan, Virginia King, Richard Orjis, John Pule, Joe Sheehan, Young Sun Han and John Walsh.

I first learned about the exhibition from Anna-Marie herself, when we met through the Emerging Curators Programme in 2015 (I was the one emerging and she one of our mentors).23 The show sought to challenge ‘our dogged cultural allegiance to Europe’, and its accompanying publication — featuring essays by Anna-Marie, archaeologist Atholl Anderson and historians Tony Ballantyne and Brian Moloughney — offered historical connections between Aotearoa, the Pacific and Asia, stretching back to the 19th century and beyond. As with Yuk King Tan’s 1990s work, I could only experience The Maui Dynasty as an idea, and through documentation of a moment already passed. Even so, it was a spark that set my work aflame, influencing my exhibition making and writing in the years that followed.

There have been other second-hand influences for me, too; other conversations I’ve only come across after the people speaking had already left the room. Just as I began the internship that was my first curatorial job, art historian and curator Vera Mey was in the final year of her tenure as the Assistant Director at ST PAUL St Gallery and about to leave Aotearoa for Singapore. She was, as mentioned earlier, interested in positioning Aotearoa within a wider cultural context and faced the challenge of finding others here who shared this orientation. Reflecting on this time, Vera wrote in 2016:

I was eager to engage an expanded discussion on the Asian Pacific geo-terrain. The types of engagement at that point in time were still under-discussed within a New Zealand cultural framework. We were aware of the rise of the “Asian century” but still configuring how to be part of it. The current conversation is thankfully progressing but there is still a distance to go before being conversant in this arena beyond acknowledging a history of Asian diaspora in New Zealand. … It can feel as if we are still figuring out where we want to be and with whom, whether that be Berlin, the Pacific or otherwise.

The Asia-Pacific Century: Part One, Enjoy Contemporary Art Space, 2016. Curated by Emma Ng and Ioana Gordon-Smith

Photo by Shaun Matthews

Writing in 2020, Lana Lopesi described The Asia-Pacific Century, an exhibition project I produced with Ioana Gordon-Smith, as a kind of anticipatory moment in the shift towards “Asia-Pacific” thinking. Our project began in 2016, when I worked at Enjoy in Pōneke and Ioana worked at Te Uru in Titirangi, Tāmaki Makaurau. We used the idea of “Asia-Pacificness” as an alternative lens for Aotearoa identity, as a counterpoint to the British colonial axis, and as an investment in the Statistics New Zealand projection that, collectively, the nation’s Māori, Asian and Pacific populations would soon grow to make up over 50 percent of the total population. We took the idea of the “Asia-Pacific” — a geopolitical and economic regional construction — and played with it at a “human scale” with a group of invited artists and contributors.

We drew on others in our networks to feed these ideas. We got the group together to discuss Epeli Hau‘ofa’s ‘hole in the doughnut’ and the films of Mandrika Rupa. We considered lei-pā, a project connecting food practices across Asia and the Pacific, to be a sister project: Lana Lopesi and Ahilapalapa Rands took part in The Asia-Pacific Century and Ioana and I wrote something for lei-pā. We interviewed Local Time, an art collective whose work has always been attuned to the dynamics of guest and host in settler colonies. We brought in materials from Anna-Marie and drew inspiration from The Maui Dynasty (2008–9).

As you can see, Lana's assessment is flattering, but it gives us too much credit. A shift was already well underway and our project had antecedents. Pākehā curators have also ridden the wave. The year before The Asia-Pacific Century, Te Tuhi had presented These stories began before we arrived (2015), which featured Taiwanese artists alongside Māori artists and was presented in Taipei and Tāmaki Makaurau. The curators, Jamie Hanton, Charlotte Huddleston and Bruce E Phillips (who had travelled to Taiwan together on an Asia New Zealand Foundation-funded tour), described the project as an acknowledgement of those Asia–Polynesia migratory links, the same ones seized upon by Ngan and Anna-Marie.

Since 2016, this shift has picked up momentum through the work of an emerging generation of Māori, Pacific and Asian artists and curators, including Robbie Handcock, Dilohana Lekamge, James Tapsell-Kururangi and Amy Weng. These curators bring artists together within frameworks of connection and relation that are more about identification with each other than international relations. An example that sought to lay historical foundations for such ideas is The house is full (2022), curated by Dilohana Lekamge for Te Tuhi. The exhibition featured the work of four artists working from the 1970s onwards: Emily Karaka, John Miller, Parbhu Makan and Teuane Tibbo. The basis for bringing these practices together was that ‘Their visions of home were not of Britain, but of a home in Aotearoa and homes that were elsewhere.’ Bringing contemporary thinking to historical practices, the exhibition proposed a reconsideration of both the past and the future in tandem.

When Ioana and I were assembling our group of artists and researchers to participate in The Asia-Pacific Century, we talked about inviting people who have ‘skin in the game’. Building a framework to act as a shelter for your own sense of belonging is both a deeply vulnerable and inevitably political undertaking. The most compelling artworks don’t just reflect their context, but are also active things — exerting their own cultural, emotional and intellectual force on the world around them.24 Art is one of our tools for building relations of solidarity, and this is what many Asian artists working in Aotearoa today are trying to do. Rather than banging on the door of a European-derived settler art canon, some are instead focused on the invitation to whakawhanaungatanga — whanaungatanga being a specifically Māori framework for building relations, and a pathway for Asian tauiwi to feel at home while supporting mana tangata whenua.

⁂

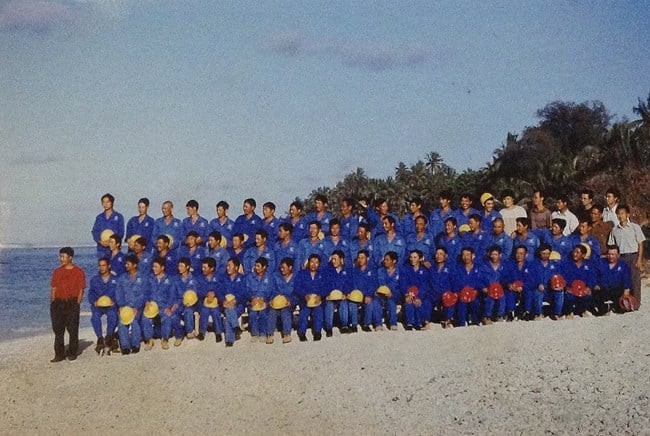

In 2004 Yuk King Tan made a work called Island portrait. It features a photograph of sixty-one Chinese workers in blue coverall uniforms each holding a hardhat. An accompanying video shows the workers being arranged for the photograph by Tan, settling into orderly rows on a white-sand beach. It’s a sunny day, and behind the group tropical trees graze a clear sky.

Twenty years later, Island portrait is a work that continues to speak to the tense geopolitical relationships that crisscross Asia and the Pacific. The workers were migrant workers in Rarotonga, “gifts” from the Chinese government, temporarily in the Cook Islands to build the national courthouse, a project fully funded by China as part of a larger attempt to exert political influence. It is an artwork that refuses the simple formulations of identity and identification that are sometimes imposed on Aotearoa Asian artists — and at other times self-imposed. It is a work whose purpose is to stir unresolved and uncomfortable questions: What are we to make of Yuk’s relationship — as a diaspora-skipping Chinese artist — to these workers, who represent the interests of the Chinese state? What does it mean for either to be in Rarotonga? And given state censorship in China, is there a role for Aotearoa to play as an exhibition venue for watchful works like this?

Both William Gee’s carving and Island portrait signal the conversations that await if we look closely at our Aotearoa Asian art archive. So much is still held in living memory by artists and curators — these are pieces of history to get a good hold of before they slide into shadow. There is plenty yet to say, and plenty that these art practices can contribute to our understanding of Aotearoa, and its relationship with other places that we hold in our network of relations.

Let’s keep rattling the shelves — who knows what else might fall out.

Yuk King Tan, Island portrait, 2007