Spatial designer Micheal McCabe looks back at his first decade of practice and the relationships that have shaped it. How do the stories we tell about our work align with how we really felt as they were unfurling? And when is it time to start telling new stories?

I’m on the phone with Emma, sitting on a wooden bench. There is a downdraft to my left that pushes across my apartment’s courtyard. I angle my body away to avoid the wind and check if it’s easy for her to hear me. At my back are concrete planters with short grasses, shrubs and a palm tree creating a small shadow at the knuckle of my hand. On this call I try to reflect on what has been ten years of making. This decade is organised on my laptop in a series of project folders, each given a year prefix ‘24-’ and a project number ‘-01’. Inside there are sub-folders cataloguing each stage of design and resources in/out. At times, these projects work across years, indicating a longer engagement with people, project and place. This systematic organisation works against any conceptual arc or narrative that can be traced from blue folder icon to blue folder icon.

If my practice can make any sense of itself, then it might be through its casual slip across disciplines. It often dresses up in whatever method is at hand.1 I try not to think about this as an inconsistency of practice; however, designing can often feel like fitting a brief and disappearing into the background. In architecture school, a fellow student said to me, ‘We are just service providers, Micheal’ — not creatives, and certainly not artists. I’ve carried this thought for a while. It has anchored my practice in the present, focused on fulfilling briefs, solving problems and having fun. I’ve used it, too, as a way to hold back time, to create a distance between the work I’m doing now and possible futures. Moving into the next decade of my life, there is a weight that sits with me; it’s not a yearning for meaning but it is asking to find where my work is directed. In writing this, I’ve begun to wrangle with that feeling. To know I eventually have to become ‘the driver’ even if I don’t have a learner’s licence.

✲

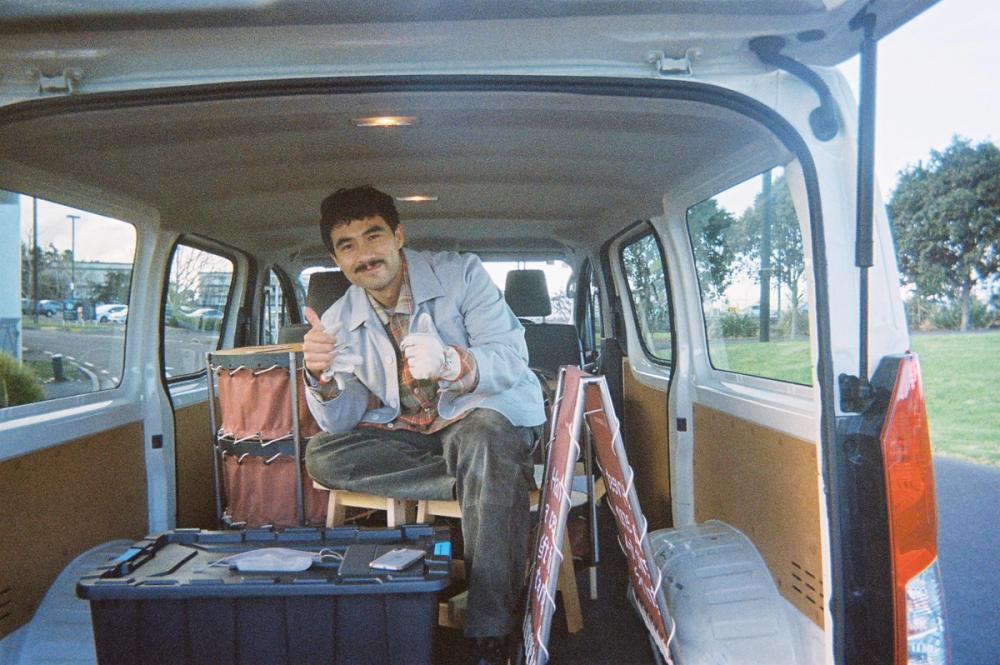

Photo from graduation of MArch (Prof) outside Auckland Art Gallery en route to a celebration lunch with my mum, 2017

There are many ways to convey a story about your own practice, its component parts, the theories it engages with, and the communities it relates to. Now, as an architecture lecturer, I have been retelling the story that I made for a lecture series organised by SANNZ (Student Architecture Network New Zealand) in 2019. The lecture begins with an introduction. A list of basic biographical details is laid on top of a photo taken of me by my mum. I’m in a cap and gown on the way to a graduation lunch. I’m wearing a striped shirt made the night before. My head is tilted upwards, a closed smile and legs twisted into the ground. The next slides are a timeline, tracking life events, projects (set design, acting, installations), student-loan debt and total yearly income. These are shown as a crush of thumbnail images, icons and red/green lines. Collectively they seek to open discussions about practice, to show its elements (professional and personal), and allow students to imagine how these have played a role in shaping my work.

Rehearsal of Odyssey shipwreck scene by Company of Giants in Quarry Gardens, Whangārei, 2013

The first time I thought about my practice was in an essay written at university. It asked, ‘Where do you want to be after this degree?’, or something similar. It felt impossible to confess that after all this time I wasn’t that interested in becoming an architect. I reconciled my relationship with architecture by talking about practices such as Assemble2 in the UK (prior to their winning the Turner Prize in 2015). Where I had really been spending my joy was in quarries and decommissioned recycling plants, making theatre in my hometown of Whangārei. I thought about translating devised theatre practices into spatial ones. I imagined a melding of these selves, architecture and theatre, to bind my work, separated as it was across humid northern summers and semesters spent in studio in Tāmaki Makaurau. I can begin to trace this vision of practice in the early piecemeal projects I took on: designing sets, a brief stint as an artist, a public installation with Satellites. I don’t include this prophecy in my presentation, maybe because I don’t believe in manifestation, but I can see a confusion in how this all begins. Where do you start, and how do you keep going?

Timeline of work from 2016–2019 mapping teaching, projects, misc events, student loan and income. From original SANNZ ‘Off-Route’ lecture, 2019

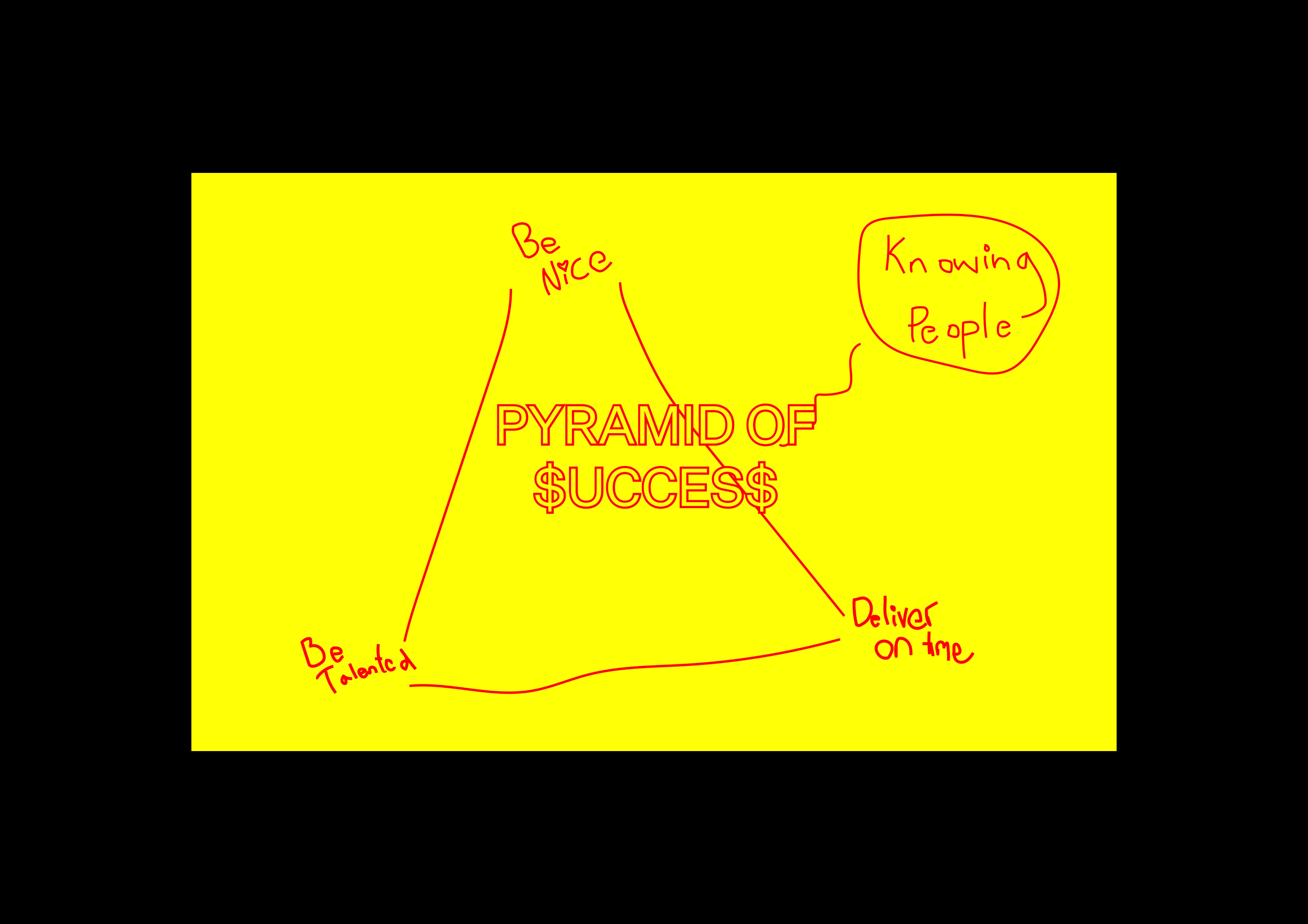

Pyramid of success diagram. From original SANNZ ‘Off-Route’ lecture, 2019

In the slideshow, I try to answer this in a set of practical learnings scrawled onto now outdated memes. I talk about paying expenses in advance, taxes, and making time for holidays. Practical things that I wish I had learned between leaping from production week to installation.

Then comes the slide I think is the most important.

It is an evolving diagram showing all the people I have worked with and the projects they are linked to. This begins with my high-school drama teacher, my boyfriend (now husband) and my university. Within two columns a community of people begins to appear. Names repeat themselves on either side of projects. Or projects cascade into one another. I hold on this slide. I look out to the room. I begin explaining the origins of these relationships. I talk about summer breaks spent inside the drama costume room sorting through piles of army surplus, tuxedos and shell jackets. How my drama teacher always thought I would come back to the arts after my architecture degree. How I refused this. How he was right. How he played a part in connecting me to Massive Theatre Company, who believed in my work when I was only ever keeping my head above water. How my boyfriend introduced me to his friends and how that opened up what was possible in Tāmaki. In parts of this story I’m pacing on phone calls. I’m in my university staff kitchen with an iPhone pressed to my ear while Elisapeta Heta says she’s too busy to take on a show at Objectspace and thought I would be good for the job. I joke that all of this is cronyism, and it is a little bit of that. Yet these relationships are central to the story of my practice. I take a moment to pause and drink from my water bottle. I’m in a wide rectangular classroom with a large window at the back. Clusters of tables with three or four students look back at this diagram. I’m not sure if my slides can ever convey the intensity or importance of these connections. Like the folders, there is not a clear arc to these names, and the way they move into one another appears arbitrary. It doesn’t capture the reality of meeting people for the first time or the moment when trust between collaborators is formed.

Ruby Chang-Jet White breakfast cart in Ōtahuhu bus station overbridge, Satellites, 2017

Photo by Julie Zhu

Projects are introduced in chronological order. Green page, project title, collaborators, and a rough budget all in red text outlined with yellow. Each is introduced with working images first: drawings, CAD models, workshop production. Then the work installed: wide angles, action shots, details. I begin this section with my first Satellites project, working alongside Ruby Chang-Jet White and Rosabel Tan, creating a pop-up food cart that served Malay breakfasts to students and workers on their commute to the city. In this project I talk about the process of creating working drawings, applying knowledge from architecture school to temporary structures and engaging tendering processes with fabricators. I talk about my naivety throughout this process and how some design intentions — like making this tall yellow structure mobile — ended up being more ornamental than functional. There is an image I don’t have in my presentation. It’s taken by Rosabel. I’m standing next to the food cart, shaved head, with a tired and collapsed posture. It’s the night before our installation in Ōtāhuhu. Something doesn’t fit right and we are troubleshooting with a drill and nudges of a rubber mallet. There is a calm stress in the workshop but the problem is solved, the structure loaded onto the truck, and the next morning we are in Satellites red and eating kaya toast. I look back at these moments and see the ambition, joy and testing of ideas as the kind of revelation you might only have when you are naive. There is a certain force that exists in early projects that feels less present in my mid-career. But I can revisit this unknowing ambition while presenting my early projects: the curved brick plinths in Company of Potters, the shonky restaging of my thesis at Window Gallery, early sketches for The Claw. This work often needs trust and generosity. It needs a belief, possibly not your own, in the potential of these ideas. It needs gentle support when the vision doesn’t quite fit or needs a bit more time. This hope in early practitioners is what lets them emerge, ground, settle and grow.

I look back at these moments and see the ambition, joy and testing of ideas as the kind of revelation you might only have when you are naive.

Screengrab of CAD model for twisting, turning, winding, 2021–22

About 4/5ths of the way through the presentation I discuss more recent projects. These become unexpected points of convergence of previous work and collaborations. Twisting, turning, winding: takatāpui + queer objects becomes a melding of relationships: Richard Orjis (Queer Pavillion, 2020), Kaan Hiini (Auckland Pride Board), and Kim Patron and Zoe Black (Objectspace). Richard envisioned this exhibition as a living archive of fify-plus objects; forty-nine artists presenting diverse and divergent approaches to queer object-oriented practices in Aotearoa. Conceived in 2021, the initial one-year timeline begins to draw out in the midst of lockdowns. In our homes we meet through intermittent Zoom calls and move through the exhibition marking up digital models with blue/purple/red lines. I place objects as digital stand-ins, move them back and forth, rotate plinths, extrude panels and cycle through possible colours and material textures.

Opening of twisting, turning, winding at Objectspace, 2022

It is strange to have all this time but there is still this churning of work. On my laptop is a blue folder that holds this collection of decisions catalogued in NURB surfaces, vectors and presentation PDFs. The lockdown lifts and the exhibition takes its form. There are two exploded ‘vitrines’ at acute angles in the centre of the room. Made of black Unistrut and tensioned mesh panels, they rest on gloss-pink footings (plinths). The back wall is painted in Resene Nightclub. On the perimeter there are variations of these vitrine-esque structures pushed into and out of the walls, cantilevering off them or creating bridges between. We place the work throughout the room using the digital model as a guide, negotiating size, material, media, relationships. The space becomes filled with work, it hangs from the grid above, sits on projecting shelves, table tops, low plinths, occasionally on willing columns. In plotting out these objects, conversations appear between them. A surfboard and a disco ball. Sheet masks and chest binders. A cream-lacquered sheet of ply and a film of chopping wood. The exhibition becomes a way to feel the distances between practices. To acknowledge the variance within them and how to tell similar stories differently.

I have not updated this timeline since presenting and five years on, it feels impossible.

Again, I reach for my drink bottle. We open up for questions, and in the silence I tug at the lid of the bottle, unwind the silicon seal and drink. There is only time for a couple of hands to pop up and ask about the presentation. I’m not great at giving a solid answer. I ask, ‘Did that make sense?’ at the end of long answers. I pull out the HDMI cord and bundle my laptop into my bag. This year is the last time I will present this story of my practice. It’s a story about quantity. About making things quickly. Rabid energy. Of testing the boundaries of what a body can do. I have not updated this timeline since presenting and five years on, it feels impossible. I look back at those stacked blue folder icons and can’t will myself to match them.

Queer Pavillion with Mahonri & Hobbs, making a korowai for AKL Pride, 2020

Photo by Ralph Brown

✲

Back in the courtyard of my apartment, I can sense a changing of season. In the pale-green growth that appears at the ends of darkened foliage. In a flower balled tight waiting for the right humidity. A suitable climate. A rich decomposition to happen amongst its roots. In conversation with friends I have caught this turn to seasonality to think through life. Across scales, a life’s seasons capture a confluence of environmental changes, vast and small. This turn has been a tool for me to cultivate a new story for my practice. To move away from the churn of work. To more thoughtfully see my position within a creative ecology. It has become a method of reflection and, in this moment, to realise that many seasons have passed and I was just inside looking out at them. In this coming season I look to the trees that have sustained me and provided shelter, their buds caught in the sun, a transparent chartreuse. I realise now I can see the blue of the sky, feel the sear of the sun, and it’s a startling thing.