Artist Yarli Allison and art historian Ming Tiampo trace their families’ migrations as they wind across continents and wend through time — overlapping in surprising places. Their conversation, which crisscrosses the Northern Hemisphere, reminds us of the many vantage points from which these histories can be seen and the deep interconnectedness of our stories, shaped by empires past and present.

This conversation was commissioned as a companion piece to Ming’s essay ‘Activating Global Asias’, which was originally published by the Asia-Art-Activism network. Many thanks to Annie Jael Kwan for facilitating this connection!

Ming: The parallels in our personal stories are striking, and follow familiar pathways, linking China, the UK (Yarli), the Philippines (Ming) and Canada through Hong Kong. As we chat, we discover that we are the grandchildren of families with histories of multiple migrations, whose lives were shaped by multiple empires — the Japanese Empire on the one hand, and the British Empire on the other — pushing our families along tides that washed them to the shores of Hong Kong and Canada at various moments in time. We are not just the children of diaspora, as it is traditionally understood as being a dispersal from one place to another; we are the products of multiple displacements, multiple histories, multiple languages and multiple cultures — what I am now calling ‘mobile subjects’ in my more academic work. These histories enable us to imagine Global Asias less abstractly, on the scale of the personal, and to think beyond the strict historical divisions imposed upon the study of Asia from an area-studies perspective, making the shift from Asia as object to Asia as subject.

Yarli, what a funny coincidence that our personal histories intersect in both Hong Kong and Ottawa, of all places! Can you tell me a bit more about how your family ended up here in Ottawa, the unceded territories of the Algonquin Anishinaabe peoples?

Yarli: We really did cross paths, didn’t we? I’ve never been able to unearth the real reason behind my family’s move, no one will say, but I first looked to the 1997 ‘immigration tide 移民潮’ in Hong Kong, one of the biggest migration waves in the city’s modern history, hoping to find clues in the anxieties of that era. Then I realised I was born in Ottawa before 1997, so that theory unravelled.

As we chat, we discover that we are the grandchildren of families with histories of multiple migrations, whose lives were shaped by multiple empires

The true motivation remains a mystery, but one thing is certain: this wasn’t my family’s first migration. My great-great-great-great-grandmother was born in England in the late 19th century, with blonde hair and blue eyes (family tales say she was either Irish or English). These features made me wonder about her and her partner’s story. Learning this fact has broadened my imagination and investigation on movements way before my parents.

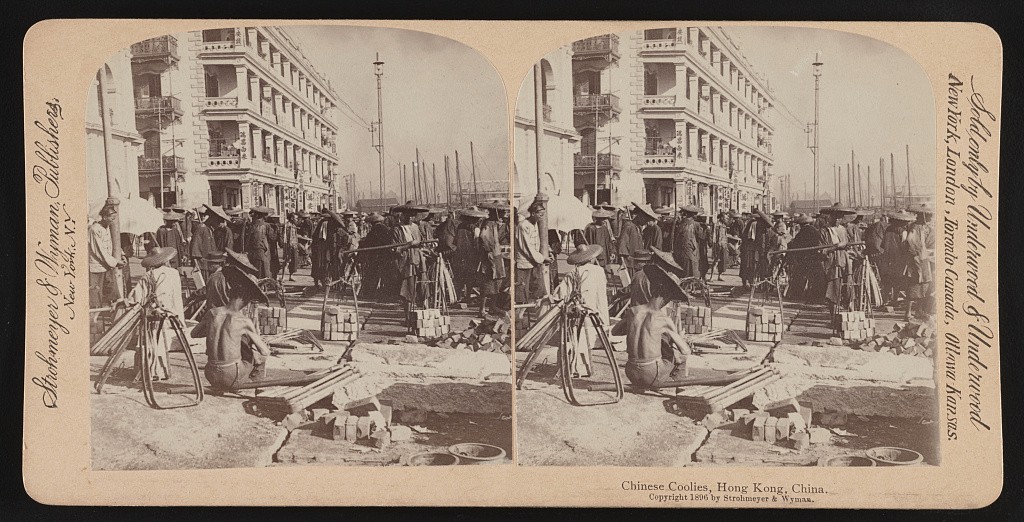

For them to have met in the early 20th century, they would have had to cross oceans, and I know they weren’t rich. Women were rarely allowed on ships unless they disguised themselves as men, were already married, or worked as servants. So the only way their paths could have crossed was if my grandpa had travelled to her side, which means he must have taken a coolie labourer job (契約勞工).

A generation later, in 1920, my grandpa was born in Canton. Somehow, he and your grandfather ended up in the same city, experiencing the same Hong Kong. They lived through a pandemic, food shortages, coolie company recruitments and the Japanese war under colonial rule.

But before I go deeper, shall we come back to you? What is your story?

Chinese coolie labourers in Hong Kong, circa 1896, stereograph. Library of Congress (98504928)

Ming: I am also the product of multiple migrations on both sides! My family left China two generations ago on my father’s side to go to the Philippines, and at least that on my mother’s side to go to Malaysia and Indonesia, eventually to Singapore, where she was born. On my father’s side, both his parents were born in China, but migrated to the Philippines as children. My grandmother went with her mother, after her father sent for them once he had established himself in the country, but my grandfather’s story is a little more complicated. Around 1910, he migrated as the ‘paper son’ of an uncle, who was a resident merchant of the Philippines. This was a way of circumventing the Chinese Exclusion Acts that applied in the Philippines, which were ceded by Spain to the United States after the Spanish–American War of 1898. According to family lore, he was only seven or nine years old at the time. He worked for his uncle for a couple of years before falling out with him, leaving his household for the Mill Hill Missionaries, who took care of him for ten years. Eventually, he became quite well educated, and when he married my grandmother, they started a shipping business by selling her dowry jewellery to buy a dilapidated boat. By the 1930s, with the expansion of the Japanese Empire and the rise of Filipino nationalist policies, they decided to leave for Hong Kong, which, as a British colony, may have seemed safer. Eventually, they left for Canada after immigration laws were changed to a points system in 1967, ending officially sanctioned race-based discrimination in the process.

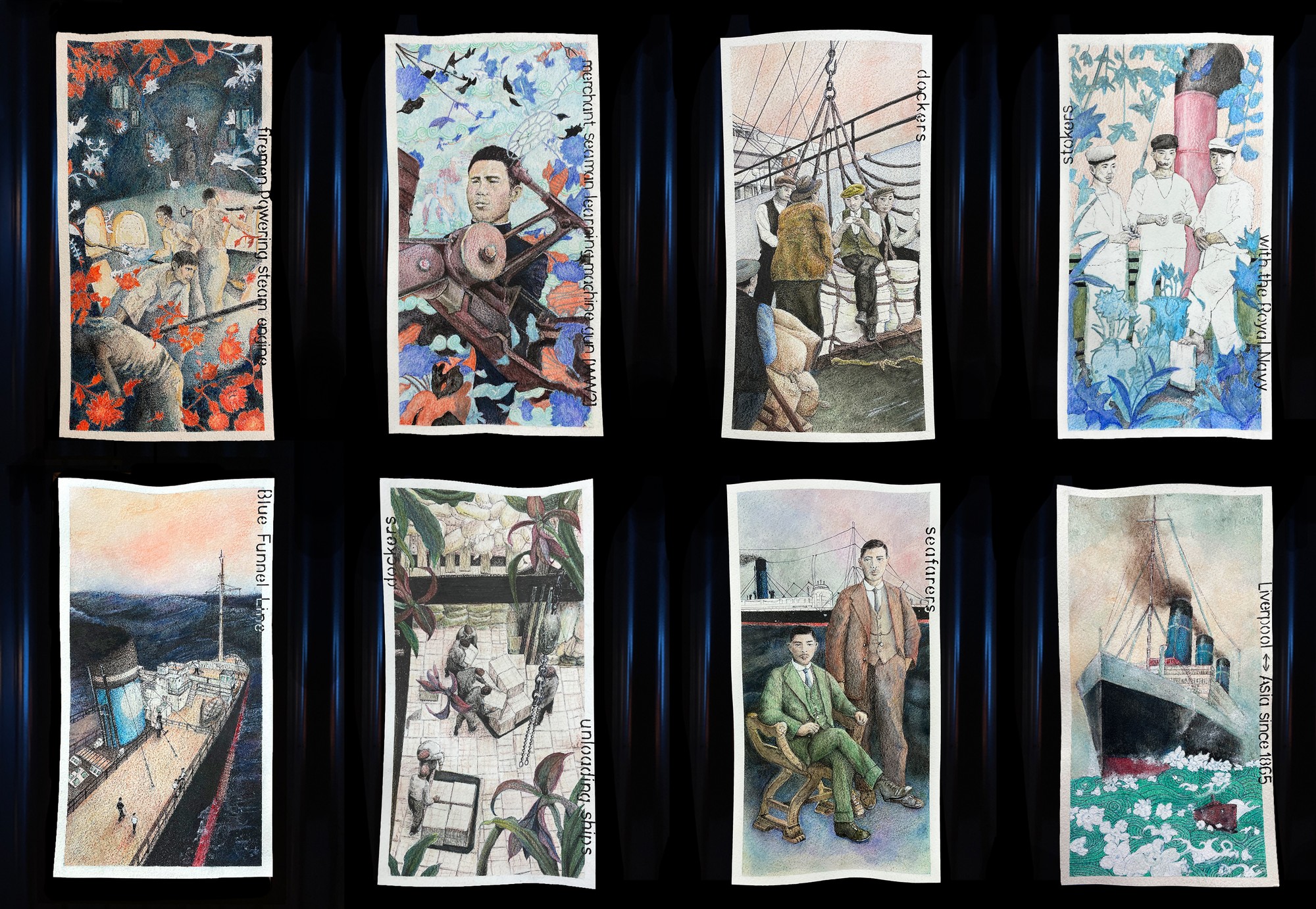

I guess we are both from seafarer families, and empires have shaped our lives and family histories. In your work, you grapple with these histories. Your Cigarette Cards — Ethnic-Chinese Seafarers in Britain 1900s series surfaces these early histories of migration. I love that they are cigarette cards, which seem to me almost to be seafarers themselves. These circulating collectibles give value to the stories of these sinophone seafarers and their labour, and point out the critical role that they played in the British Merchant Marine fleet.

Can you tell me what the inspiration was for making these cards, and what you were thinking when you were making them?

Yarli Allison, Cigarette Cards — Ethnic-Chinese Seafarers in Britain 1900s, 2021, watercolour, pencil, ink and gouache on 100 percent cotton paper, 31 × 16.5 cm each, set of eight.

The work was commissioned by FACT, Liverpool, curated by Annie Jael Kwan, with the support of public funds from Arts Council England, Liverpool City Council, and the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme project Artsformation. With additional research support from CFCCA with the support of public funds from GMCA.

Yarli: The cigarette cards are definitely collectibles! My grandpa, a heavy tobacco user, used to collect them. I noticed there wasn’t any Asian representation, at least not without the lens of Orientalism. So I did some research. There were Asian women, soldiers, seafarers, flowers, animals, objects, traces of ‘exotic’ fruits, everything, except the 20,000 Sino seafarers who worked for the British Empire. So drawing my ancestors became a tribute to honour their presence and their labour above and below decks, the hands that powered the steamships that powered the Empire; they existed.

Ming: I’m assuming that your haunting video work, In 1875 We Met at the Docks of Liverpool, is telling the story of your great-great-great-great-grandparents? I was struck by your evocative description of the hellish existences of the coolie coal stokers who shovelled prodigious quantities of coal into the engines of British ships — literally feeding the engines of Empire — and how that same Empire disavowed their contributions and their right to belong, tearing families apart and even disenfranchising the British women, like your great-great-great-great-grandmother, who married them. The story of Ah Sun’s deportation is so heartbreaking! In our current political climate, where deportation appears to be the solution to migration paranoia, your work provokes questions about belonging — who belongs and why? How are people assigned to countries of so-called origin, to which they are then deported? How do race and gender intersect, and where does personhood reside, if a woman could lose her status as a citizen for marrying an ‘alien’?

Why did you choose to make this work based on your family history?

Yarli Allison, 'In 1875 We Met at the Docks of Liverpool' (trailer), 2021

Yarli: As I worked to rebuild the disappeared Eurasian town or Chinatown in virtual reality (VR), I began to notice colonial traces I had overlooked growing up in Hong Kong. I started to ask: How do I expand my family history to a larger scale? And more personally, I wrestled with a sense of collective belonging and grief. It felt unsettling to know the streets my ancestors once walked on in Liverpool had been bombed. What became of their displacement and memories when no physical trace remained? How did their partnership survive so many obstacles while raising children in such a challenging environment? As you mentioned, for your great-great-great-great-grandmother to give up her citizenship in order for them to be together, their love must have been driven by forces far beyond practicality and social pressure. Officially, none of these stories were documented, so making this work was a form of validation, making their stories visible.

It felt unsettling to know the streets my ancestors once walked on in Liverpool had been bombed. What became of their displacement and memories when no physical trace remained?

Yarli Allison, 'Walking in the disappeared Chinatown', 2021

You mentioned the wars, too. Sino seafarers in Britain lived under constant uncertainty: on one hand, the threat of German U-boat attacks, knowing a colleague’s ship sank yesterday but still needing to work today; on the other, the unknown fate of their families in the Sino–Japanese War. And then, what was their future in Britain, where they were never fully welcomed? Many had already built families there, only to face repeated repatriation between World War I and the aftermath of World War II. So, with the British repatriating these Sino seafarers, what became of the couples and children sent back to a post-Sino–Japanese war zone?

To get a holistic view, I started interviewing the descendants of seafarers now in their retirement years, visiting merchant seafarers’ graves and gathering oral histories to uncover the story.

Ming: Wow, that’s amazing. What did you find out? What role do you think personal stories have in enabling us to connect with history?

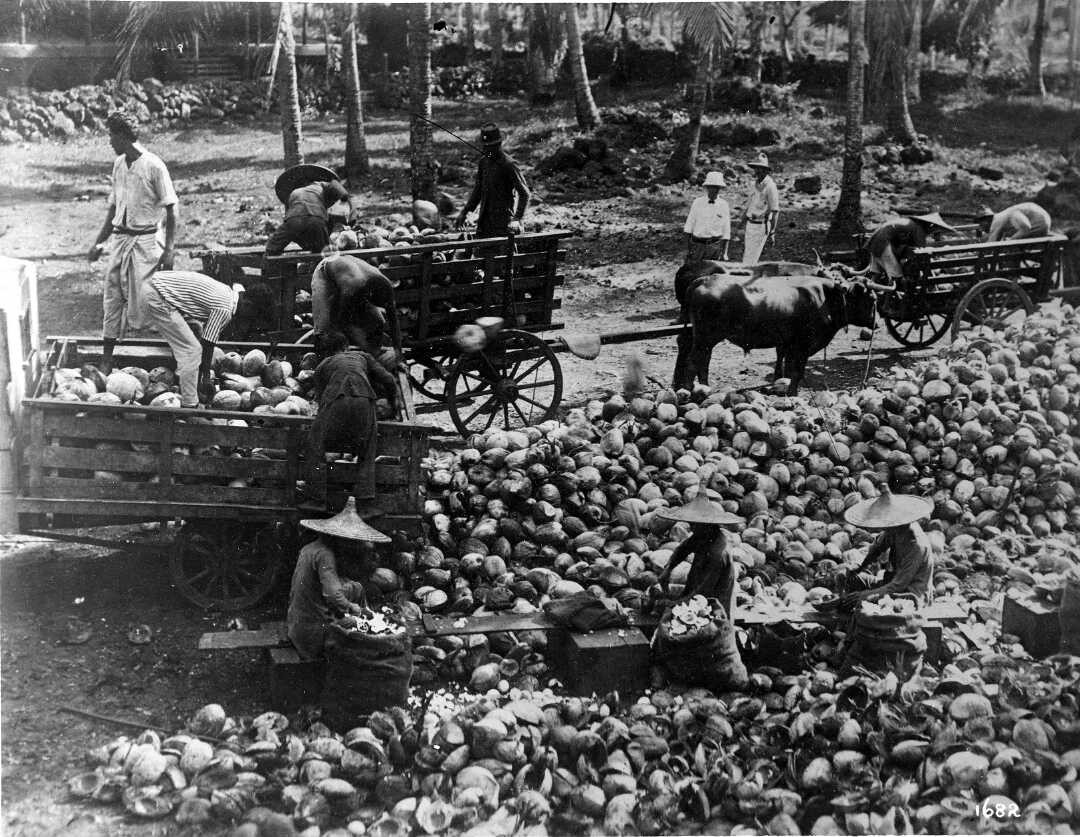

Yarli: These personal stories make history tangible, bringing to life the struggles, resilience and everyday experiences that official records often overlook. Take the early sinophone seafarers in Britain as an example; despite coming from different regions, speaking different languages and having different food cultures, they were grouped as a single ‘Chinese’ workforce. Some lost their lives at sea working for the British Merchant Navy; their names were misspelled or lost in official records, and their families were left with unanswered questions after forced repatriations. When we uncover these personal histories, even in fragments, we see history as more than policies or wars, it’s about being human, the choices made, the connections formed and the legacies left behind.

Coconut industry labourers in Samoa, circa 1910, with Chinese workers cutting out copra in the foreground. Alexander Turnbull Library (PAColl-7081-49)

Ming: What do you think these very personal tales contribute to our understanding of ‘Global Asias’?

Yarli: These personal stories reveal that ‘Global Asias’ is about the gaps in history, what gets remembered, erased and reclaimed. Our families’ stories, like many others’, weren’t neatly recorded; they are fragmented, passed down through half-told memories, misspelled names and vanished places. Reflecting on my ancestors’ movements and the displacements they endured makes me realise how much survival has shaped who we are today. Yet these stories don’t fit neatly into national narratives. Where do they belong? Who decides?

When we talk about ‘Asia’, it’s often framed by national borders and top-down histories. But family histories show Asia in motion, entangled histories shaped by migration, labour, empire, war and generational lives. ‘Global Asias’ is about lived experience, real people, real choices, real consequences.

It’s in the overlap of histories: how my grandfather and yours walked the same streets in Hong Kong, shaped by the same forces of empires and wars. These personal stories fill in the gaps, reminding us that history isn’t just about nations, governments and wars, but about people, storytelling and remembering.

‘Global Asias’ is about lived experience, real people, real choices, real consequences.