Brannavan Gnanalingam reflects on the growing thicket of Asian writers in Aotearoa — and the exhilarating relief of crafting his own universe of South Asian protagonists who are by turns sympathetic and just plain pathetic.

I’ve just published my novel, The Life and Opinions of Kartik Popat, which is my eighth since 2011. I admit that’s quite a feverish pace, which is probably explained by the fact I’ve had close relatives die of heart disease and war by their forties (I’ve just turned forty-one). For a number of years in that period, I was one of only a handful of writers of Asian heritage published in the literary fiction enclave of Aotearoa publishing. There are of course earlier trailblazers, such as Alison Wong, Ant Sang, Nalini Singh and Vasanti Unka, among others, who have carved out their own spaces within their genres of choice, and they remain significant and underrated figures in our landscape. But in the literary fiction spaces, aside from Wong, it felt like crickets, particularly when I was first starting out. However, I was lucky enough to find a fruitful partnership with the anarchist publisher Lawrence & Gibson, and my key collaborator Murdoch Stephens, who has had no qualms in publishing whatever I’ve decided to write about (via a rigorous process, of course).

Brannavan Gnanalingam printing and binding his novel Slow Down, You're Here with fellow Lawrence & Gibson publishing collective member Thomasin Sleigh, April 2022

Janis Freegard has been carrying out an analysis of novels and poetry published in Aotearoa over the last decade, breaking it down by gender and ethnicity of the authors — admittedly, she says, on a best-guess basis. Her analysis shows that, proportionally, writers with Asian heritage have been published in far lower numbers than their proportion of the population. In 2015, 4 percent, or three out of the sixty-eight novels published, were from writers of Asian heritage (I can count my third book, Credit in the Straight World, as one of those). In 2019, it was 7 percent, compared to 15 percent of the population at the time. I accept that there are, frequently, different drivers for immigrants, in which parents and children can be initially focused on economic considerations, and less on artistic pursuits. However, there has also been a noticeable shift over the last ten years, arguably as many of us early immigrants/1.5ers, who arrived in the 1980s and 90s, started to find our voices and find audiences that looked like us.

It becomes a bit of a self-fulfilling prophecy, being so invisible in the literary space. Publishers decide there’s no audience for ‘minority’ literature (assuming that a minority writer only wants to write about so-called minority issues), and therefore those writers don’t trust or submit to those publishers, and therefore their potential audiences don’t feel served by such publishers, and the cycle perpetuates. The pioneers made their own way — Ant Sang self-published, Vasanti Unka came through illustration, and Nalini Singh was first published by a North American romance publisher.

The obvious fact, although perhaps less obvious to publishers, is that I’m a writer because I like to read. I was a tutor and occasional lecturer for a number of years in the Asian cinema paper at Victoria University, and a regular writer on Asian and African film movements and directors for The Lumière Reader, but I came to realise my reading habits didn’t match my adventurous and diverse film tastes. In my twenties I started devouring the post-colonial literature of West Africa and the Caribbean, and Black American writers, and then shifted to reading writers from all parts of Asia, Africa and the Middle East, on top of whatever else became popular or was published here. The obvious result of that is that I thought, if people like me could write, I could too. I assume that is the journey for many of us who have taken up the pen. I got lucky finding Murdoch Stephens and Lawrence & Gibson for my first book, Getting Under Sail, and I guess I got published in a classic Aotearoa way — a friend passed it on to her ex who passed it on to Murdoch, and that was it.

I thought, if people like me could write, I could too. I assume that is the journey for many of us who have taken up the pen.

Booklet published to support the Double the Refugee Quota campaign, 2016. Te Papa (GH024819)

It took me a while to find my audience. My first four novels satirised race and liberalism (among other things), but my first novel that explicitly dealt with my Sri Lankan Tamil heritage was my fifth, Sodden Downstream. It is about a Tamil refugee cleaner’s trip to the Wellington CBD, when all access has been cut due to a storm, written in part as ‘literary ballast’ for Murdoch’s successful campaign to double New Zealand’s refugee quota. It is also about what survival means for someone who has gone through unimaginable trauma (surviving the utter horror of the genocide in the last days of the Sri Lankan Civil War in 2009), but also the impossibility of starting over as if nothing had previously happened. My relationship to the Sri Lankan Civil War was extremely different to Sita’s — I was a middle-class immigrant to Aotearoa in the 1980s, not a refugee like Sita and her family. I also had distance from the apocalypse at the end of the war, but I felt some obligation to try my best to capture it.

Sodden Downstream only sold sixty copies in its first five months. While profit isn’t the main focus of Lawrence & Gibson, I also didn’t want to wipe out all of their savings. If I had been with a traditional publisher, that would have been the end of things. The book, however, was ‘saved’ by being longlisted and then shortlisted for the Ockham New Zealand Book Awards. It is now probably the book that most people have talked to me about to this present day. It also made me wonder about the freedom I’ve had with Lawrence & Gibson, and the time I’ve been given to get better, something very few Asian immigrant literary novelists have had in Aotearoa. I don’t think I’d have improved enough as a writer to feel ready to tackle the enormity of the Sri Lankan Civil War, nor take on the formal experimentation and challenging subject matter of Sprigs, without the patience of alternative publishing to let me find my voice without the need for immediate success or sales.

It also made me wonder about the freedom I’ve had with Lawrence & Gibson, and the time I’ve been given to get better, something very few Asian immigrant literary novelists have had ...

Brannavan at the Ockham New Zealand Book Awards with Sodden Downstream, 2018

Minority artists often talk about the ‘burden of representation’, the sense that because there are so few of them, whatever they do ends up standing in for the wider community. Which is plainly ridiculous, given the complexity and diversity within any community. Perhaps I felt that with Sodden Downstream, explaining why it took me so long to write about being Tamil (although, to be fair, barely anyone read me within the community, so it was not as if I had a Tamil fan-base to appeal to — that self-fulfilling prophecy, I guess). I still have no idea who my audience is, but I’ve got the sense that more South Asians in Aotearoa have read my later novels, which gives me more impetus to keep writing these stories.

That said, I’ve spent my writing career avoiding taking on that burden; I barely feel qualified to capture the nuances of being Sri Lankan Tamil, let alone an entire subcontinent, to use an ahistorical amalgam like South Asian. However, I’m also very conscious that I have a voice and a platform that could make the path easier for people who follow after me. I’d like to think the success of Sodden Downstream and Sprigs (the first two novels from an Asian immigrant to be shortlisted for the Jann Medlicott Acorn Prize for Fiction at the Ockham New Zealand Book Awards) has led to mainstream publishers in Aotearoa realising that minority immigrant stories can both sell and be critically recognised.

... although, to be fair, barely anyone read me within the community, so it was not as if I had a Tamil fan-base to appeal to ...

Do The Right Thing (still), directed by Spike Lee, 1989

I was an early adopter of ‘critical race theory’ (now derided by the right), which I was introduced to during my MA in 2007–8. My MA was on the critical reception to Spike Lee’s Do the Right Thing and NWA’s Straight Outta Compton, and the historical construction of race. While I acknowledge that there’s no way I would now dare to write in the same way about another minority group, I was introduced to heroes such as Foucault and Gramsci, Stuart Hall, Judith Butler and Frantz Fanon, among others. A key lesson was how the construction of minority labels is inherently a historical phenomenon. For example, race was initially constructed via the slave trade, and then the Enlightenment and imperialism/colonialism, and in the process, effaced difference (noting I also subscribe to the Durkheim idea that societies will always find some way of establishing and measuring difference). This essentialising approach to race isn’t a new concept, made clear by the devastating final line of Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart, where the inter-tribal interactions and conflicts of the Igbo protagonists are wiped away by a single pen-stroke from the British administrator, calling the story we’ve just read a minor footnote in ‘the pacification of the primitive tribes of the Lower Niger.’

This analysis also gave me ideas as to how to challenge our historical constructions, even if these concepts have their root in someone else doing the defining for us. As Michel Foucault makes clear, power isn’t simply a top-down approach, that there is scope to define, and redefine, and redefine. If a discursive framework is a constructed, historical process (and if, as Antonio Gramsci notes, meaning can never be fixed and can always be contested), then there is scope for minority artists to tactically challenge the frameworks. The issue I noted in my MA thesis was that however you define yourself, you cannot control your reception. (Both texts I studied created moral panics — NWA’s concerts ended up being shut down by the police and no mainstream media reviewed them, but record labels, realising how successful they were, took their style of hip hop and sanitised it for the mass market; Do the Right Thing was lambasted as encouraging its Black audience [only] to riot, and then lost at the Oscars to the much more polite Driving Miss Daisy). But worrying about the reception doesn’t mean we can’t, and shouldn’t, try.

We don’t need to add footnotes to our own histories or glossaries to our own languages.

For example, it seems utterly futile to think that a continent as diverse and complex as Asia — holding 60 percent of the world’s population — could be described in a few stereotypes or essentialist terms when it comes to us as immigrants. Yet the literary worlds in the West frequently treat Asian writers and Asian audiences as a monolith, ghettoising us into ‘Asian writer’ segments; or assuming our supposed creative drivers, or alleged lack of audience, mean that the same old clichés and narratives are the only ones that Asian (and other) audiences want to read. (Look, I don’t need to read another story about food as identity, and I’m someone who loves reading about food — which possibly explains why I initially wrote about failed finance companies in the South Island, journalists and their ennui towards Le Front National in Paris, and Wellington bureaucracy.) That’s not to say publishers aren’t capable of changing — the recent surge of magnificent Māori writers in Aotearoa, who have defiantly called for story sovereignty and have been unapologetic in their narratives (or audience expectations), has seen a myriad of amazing books and stories being released by publishers in the last ten years. These writers in turn have inspired me to never explain what I’m doing in my books, to never presume that my audience has to be patronisingly told about the cultural specificities in play (they can research, if they need to). We don’t need to add footnotes to our own histories or glossaries to our own languages.

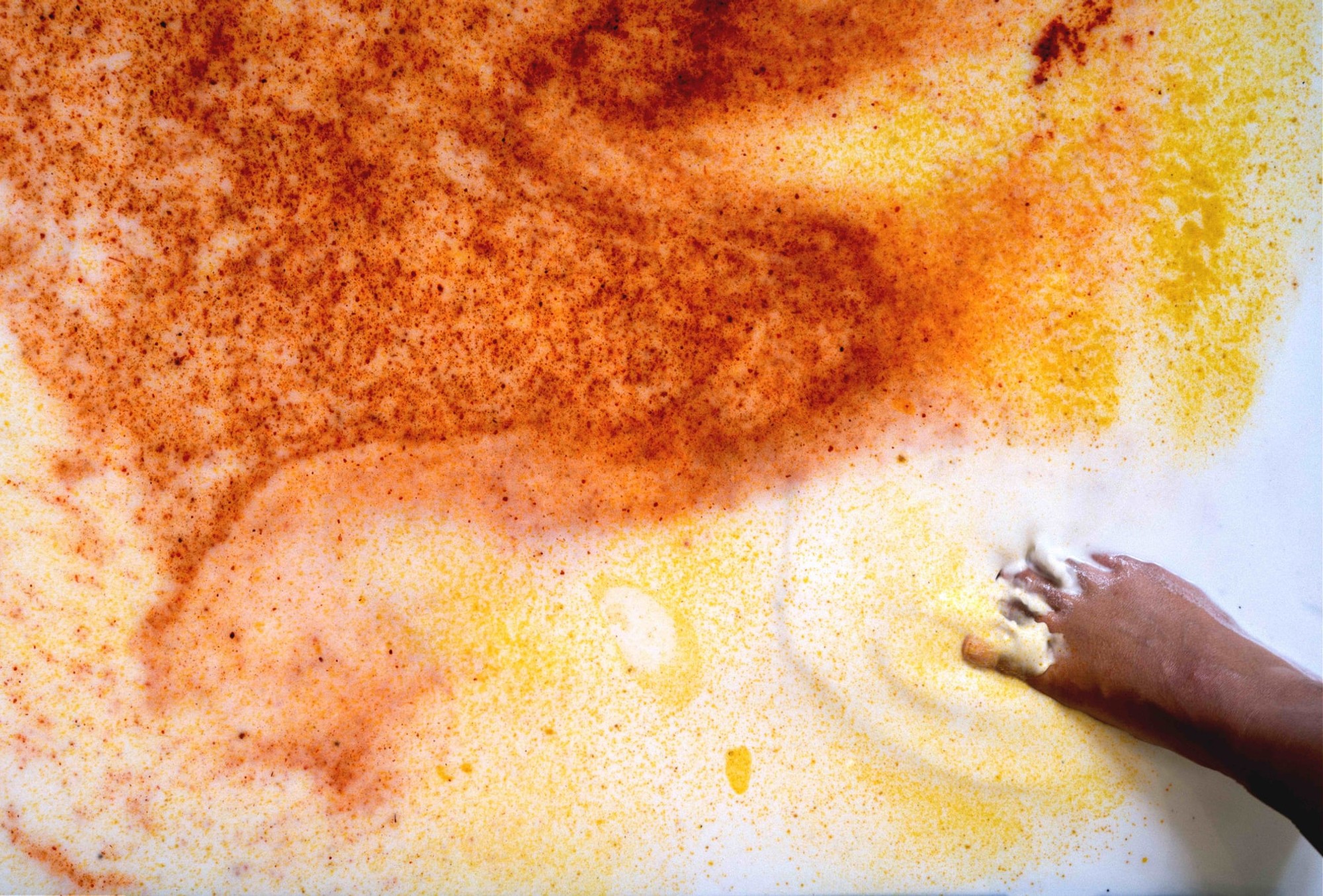

The cover image of Slow Down, You're Here, by artist Dilohana Lekamge

I’ve had a couple of key motivators as a writer. The first is ensuring people have the ability to define themselves any way they want to, but also trying to figure out how people can build solidarity in doing so; i.e., defining oneself can never come at the expense of someone else. The second is breaking down the essentialist notions that we’ve relied on to define ourselves.

Cultural theorist Stuart Hall’s idea of challenging essentialist notions, particularly stereotypes, was to move away from ‘good’ portrayals of being part of that minority, as this simply upholds a binary dichotomy. Sure, you can present a character as good in order to challenge a negative stereotype, but you’re still within an either/or, good/bad framework. His suggestion was that we make our characters and stories as diverse as possible, have as many of us as we can, to make the meanings elusive, unstable and ultimately pointless. That we can present ourselves as nuanced and complex is a nice antidote to the idea that fictive works have to be morality tales.

It’s perhaps this quest that has also driven my sheer single-mindedness as a writer, this aim to have as many different characters of South Asian, and in particular Sri Lankan Tamil, heritage as possible, knowing that I’m learning more about myself the more I write. In doing so, we can also subvert these historical constructions, as, importantly, we can talk about how we’ve constructed ourselves. Ultimately, it’s all a way of making it impossible to define us.

This is why I try to have messy, defiant, passive, useless, hard-working, broken, sociopathic, horny, ambitious, confused protagonists, such as Sita, Thiru and Satish in Sodden Downstream, Priya and her mother and grandmother in Sprigs, Kavita, Ashwin and Vishal in Slow Down, You’re Here, and Kartik in The Life and Opinions of Kartik Popat. I’ve refused to define them in ways that allow for any essentialist characterisation (or at least, I hope I’ve done so) — and I’ve found the closer I get to the shore in describing my own understanding of my various backgrounds, the longer and more nuanced the on-rushing landscapes become. I’d like to think, over my eight books, I’ve made it clear we can write about whatever we damn well please.

This is why I try to have messy, defiant, passive, useless, hard-working, broken, sociopathic, horny, ambitious, confused protagonists

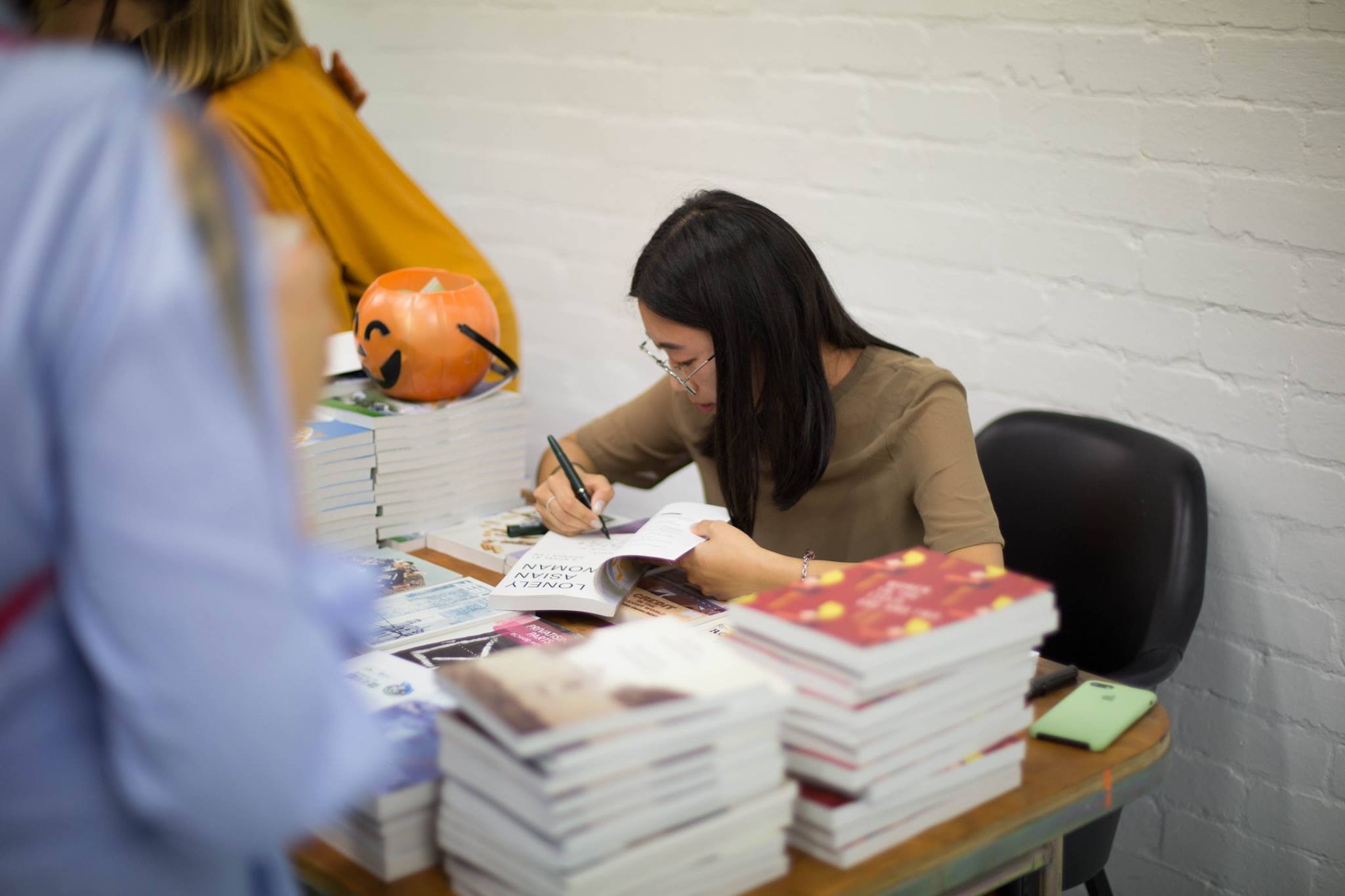

Sharon Lam signing books at the launch of Lonely Asian Woman, March 2019

The joy, though, as more and more writers of Asian heritage get published in Aotearoa, is seeing how many of my fellow writers agree with obliterating any conservatism about our narratives. I assume these writers also write without the same millstones. Surveying some of the fiction published in recent years (and that’s not mentioning poetry and so-called genre fiction), it’s clear that trying to make links between these books is an exercise in pointlessness. It also makes me want to revisit some of those pioneers mentioned in my introduction as well, and get a sense of how they used their voices to lay the groundwork for those of us who have followed.

Rupa Maitra’s Prophecies (2019) is a brilliant short-story collection of messy protagonists, both Pākehā and with Indian heritage, who frequently make mistakes in a very diverse range of settings. Maitra is particularly attuned to the internal psychology of her particular characters, and no two characters are the same in the collection. Rajorshi Chakraborti’s The Man Who Would Not See (2018) crosses between Aotearoa and India, and Chakraborti’s brilliant control of narrative creates a dizzying tale of revenge and grudge holding. His follow-up, Shakti, is a rip-roaring page-turner about an India that’s fast descending into authoritarianism and corruption (there’s no Aotearoa narrative).

The year 2019 also saw the publication of two misanthropic masterpieces set in Aotearoa, both antitheses to the model-minority idea: Huo Yan’s Dry Milk and Sharon Lam’s Lonely Asian Woman (Yan’s book was admittedly published in Australia by Giramondo, and Lawrence & Gibson published Lonely Asian Woman). Yan’s novella tells the tale of a seething shopkeeper, John Lee, who resents his disabled wife, and becomes increasingly infatuated with his lodger. The book is nasty and brilliant, and Lee’s descent into bedlam is both shocking and captivating. Lam’s book is much more gentle, but also effortlessly uses humour to particularly hilarious effect. Paula is stuck living a mediocre life in mediocre Wellington, and her life takes on an increasingly surreal twist following an escapade in the supermarket.

romesh dissanayake and Saraid de Silva signing books at their shared book launch in Pōneke, April 2024

Unity Books Wellington

Writers with Asian heritage have also been particularly successful overseas in YA, horror and fantasy — Lee Murray, Graci Kim and Chloe Gong are genuine literary superstars overseas. It was a particular joy to see Murray recognised at the Prime Minister’s Literary Awards for Fiction in 2023. Other recent novels have messed about with genre — a great example of this is Angelique Kasmara’s Isobar Precinct (2021), which is a genre-defying mix of crime, fantasy and social critique, in which Tāmaki Makaurau is presented with a grimy noir haze, capturing the city in a way few writers have come close to, suggesting an embeddedness that subverts stereotypes about immigrants.

Meanwhile, two books published in 2024 from writers with Sri Lankan heritage break apart their own characters. In when I open the shop by romesh dissanayake and Amma by Saraid de Silva, the writers complicate their characters through their narrative structures. dissanayake uses ellipsis and abrupt shifts in time to almost create multiple characters within the one protagonist, highlighting a sense of how a person can break apart under grief and reconstitute themselves at a later point. De Silva’s Amma tells the story of three generations of Sri Lankan women, who never quite come to fully understand each other’s journeys, but get profoundly shaped by all of their mistakes, their tragedies and their defiance. I’d like to think that between Amma, when I open the shop and my The Life and Opinions of Kartik Popat, we three writers of Sri Lankan heritage (in 2024 alone) have offered three very different ways of approaching our South Asian protagonists, and that our only unifying thread is our heritage (although I can also say that the first two books, at least, are terrific).

This lack of unifying thread is perhaps explained by the variety of our backgrounds — whether being born in Aotearoa, being a refugee, being a middle-class immigrant (either as a 1.5er or a more recent arrival), or being a multi-generational New Zealander. Yet it still doesn’t stop this catch-all label being used to describe us, as if our books can be reduced to our ethnic backgrounds. I adopt that approach here, though only to complicate and undermine it.

the more we write stories from our Asian vantage point, the more the term ‘Asian’, and that vantage point, can crumble away as something wildly ineffective to stand on

While more of us are being published, and importantly showing the publishing world that we are also being read here in Aotearoa, there are the battles still to come, and I suspect they’re going to be led by those of us who have found ourselves with a small space in this literary world. I know I’m going to do all I can to help other writers of Asian heritage make it in Aotearoa. But I also want to ensure we make it clear that our books are not comparable, to avoid being lumped together or played off against each other; to challenge the lazy idea that more than one Asian writer just can’t be reviewed or rewarded at any one time, or that two unrelated books can be compared in a single review. We need to be able to talk about our work as being one of craft or of ideas, and our own cultural specificities (if we want to), rather than having to talk about being ‘Asian’ and ‘exploring Asian identities’ in print or on stage.

Maybe the end goal is slightly contradictory, but that’s the nuance and complexity I’m looking for. I want to ensure that the Asian writers who come after us feel comfortable writing about their own identities, but that they’re also empowered to not write about their identities, to write about whatever they feel like. That we get to define ourselves in a way that makes a mockery of any remnants of publisher ignorance over what sells when written by an Asian writer, or the limited subject matter that we should be writing about. One thing we need to ensure is that we don’t let institutional indifference to our writing fool us — and our readers (particularly Asian readers) — into thinking our writing is inferior, or less worthy, or unable to be celebrated. We don’t need Pākehā permission to celebrate our own books. We can define ourselves despite what dominant cultures think. If they don’t get it, that’s not our problem. Effectively, the more we write stories from our Asian vantage point, the more the term ‘Asian’, and that vantage point, can crumble away as something wildly ineffective to stand on.