Art historian Ming Tiampo traces the different strands of scholarship that emerged as Asian diasporas circulated and pooled across the globe, finding the possibility of agency, connection and activism in the concept of ‘Global Asias’.

First published by Asia-Art-Activism, a UK-based network of artists, curators, and academics, this essay appears here with their support, extending Satellites’ engagement with global discourse on contemporary Asian art. In this issue, we also present a new companion conversation between Ming and artist Yarli Allison! More details on AAA at the end of this essay.

✲

I was lying in a hotel-room bed in Dhaka wracked with chills and dizziness, and felt an indescribable desire for the comforting rice porridge that my Singaporean nonya grandmother used to make for me when I was feeling under the weather.

In my Cantonese-speaking household, we called this elixir juk, but I also knew it from its English name, ‘congee’, which I had seen on the menus of Hong Kong cafés in Vancouver, Canada, where I grew up. To my enormous surprise, when I googled the Bangla translation for ‘congee’, I discovered a food history that linked the origins of my childhood comfort food back to South Asia, through Tamil Nadu’s Muslim home chefs, to a wonderful steaming bowl of kanji perfumed with ginger.

When room service arrived, filling the soul with comfort, I was overwhelmed by feelings of gratitude, entangled kinship and postcolonial ambivalence. This was a feeling that resurfaced every time I spotted Milo, Ribena or Horlicks, or some other colonial delicacy packaged by appointment to Her Royal Highness the Queen on shelves in Delhi, Dhaka, Hong Kong, Singapore, and in Asian grocery stores around the world, which, like a colonial madeleine, drew me sweetly back to my childhood, yet functioned as a punctum, a dark reminder of the reasons behind our seemingly parallel histories and shared entanglements.

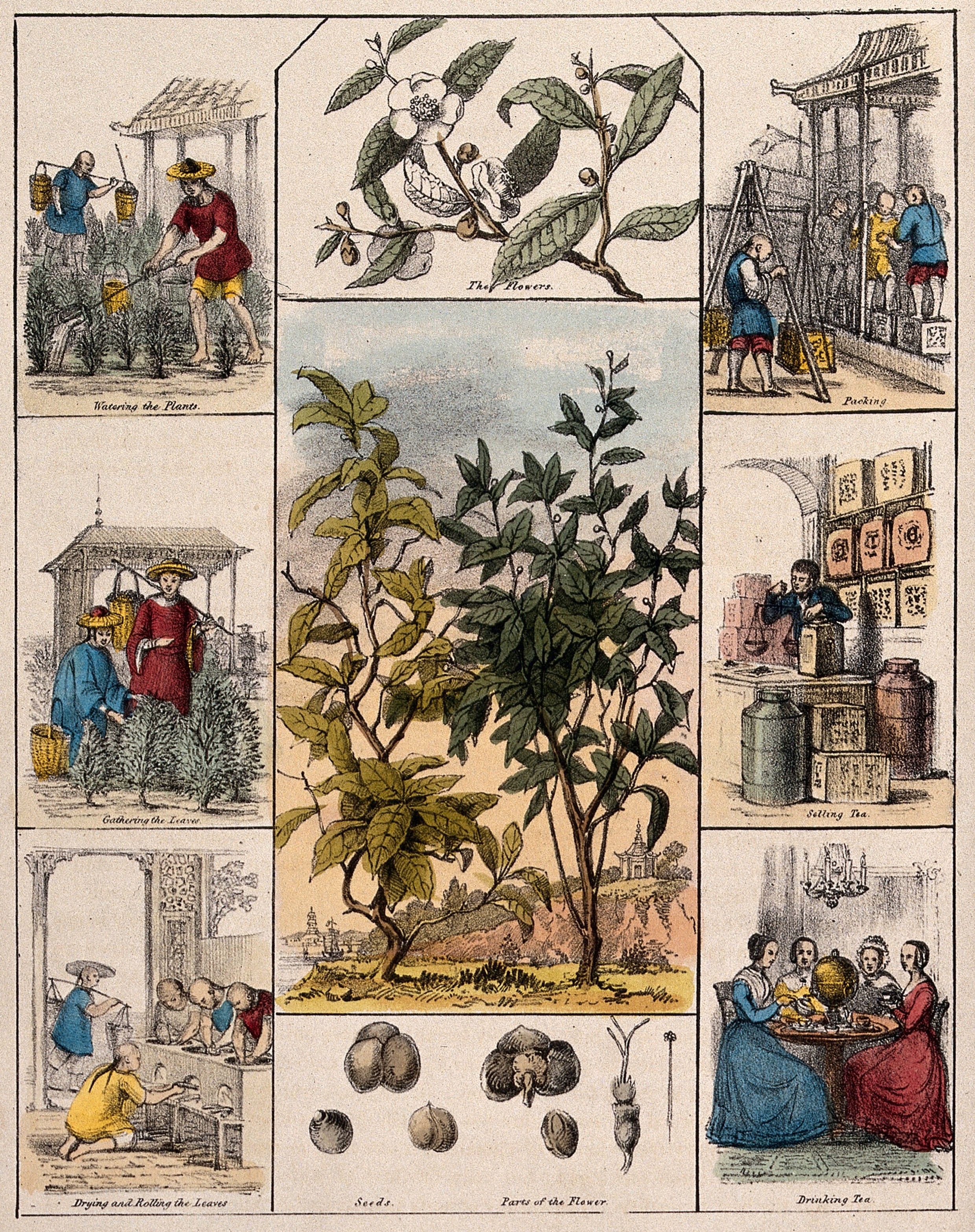

A tea plant (Camellia sinensis) bordered by six scenes illustrating its trade and use, circa 1840, coloured lithograph. Wellcome Collection (28058i)

Asia has long existed under the gaze of scientific study, segmented into geographies that rendered its territories into a neatly organised cartography of ~ologies, whose flows and movements within Asia and beyond were rendered invisible by imperial imaginings. Asian studies, divided into Sinology, Japanology, Indology, Turkology, Islamology and other fields, were, as Edward Said demonstrated, at their origins a strategic way of ‘knowing’ the Other within larger European projects of imperialism, colonialism and domination.1 Following the Second World War, American universities saw a massive growth in interdisciplinary area studies programmes that brought together the humanities with economists and political scientists, which ‘strategically planned to create academic programs that would both guide and legitimise US foreign policy.’2 After countries gained independence from their colonisers, the boundaries erected by European epistemologies were amplified by Cold War rivalries, postwar borders and postcolonial nationalisms. More recently, with the postcolonial, transnational and decolonial turns, scholars began turning their attention to encounters between Asia and the North Atlantic, at times interrogating the legacies of colonialism, at times reflecting anxieties about civilisational competition, at times seeking to understand a prehistory of current forms of global interaction. Only rarely did scholarship consider interactions within Asia or with other parts of the non-Western world, or make comparisons that would elucidate a larger history of empire and postcolony.

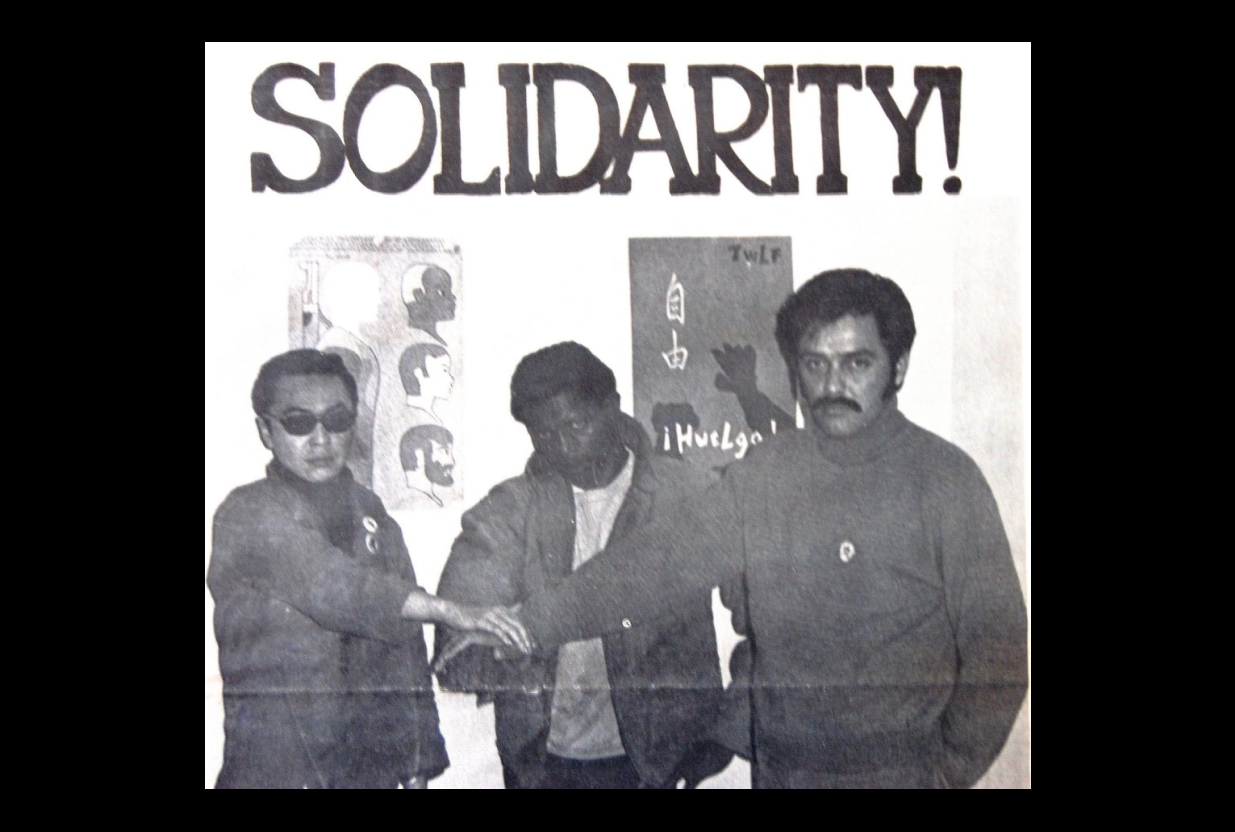

Isolated from one another, these historiographies of Asian studies also evolved separately from the academic study and discourses of Asian diasporas to Europe and North America, which emerged in the context of civil rights movements and the political unrest of the 1960s. Asian American studies arose in 1968, following a five-month strike by the Third World Liberation Front, and resulted in the first department of Asian American studies being established at the University of California, Berkeley; the first minor in Asian Canadian studies was established at the University of Toronto in the late 1990s. In the United Kingdom (UK), identity politics were imagined differently and Asian diaspora discourses emerged as a part of the articulation of political Blackness, which built solidarities among migrants from former colonies of the British Empire and their descendants within the context of Third World discourses. Political Blackness mobilised the field of British cultural studies and established its first academic foothold at the Birmingham School of Cultural Studies in 1964 with founding figures Stuart Hall and Richard Hogart.

Richard Aoki, Charles Brown, and Manuel Delgado at UC Berkeley, circa 1968

Third World Liberation Front

This disciplinary divide between Asian studies, Asian American studies, and Asian diasporic studies more broadly, was the gulf that the concept of ‘Global Asias’ was created to bridge. The concept began to frame a space at the intersection of area and diasporic studies, with a book series at Oxford University Press, and the creation of the cultural studies journal Verge: Studies in Global Asias. The two divergent disciplinary histories and historiographies of area and diasporic studies had created two separate discourses with different imagined positionalities that posed different research questions of material that was often entangled and mutually implicated. The shift enabled by Global Asias was thus not simply an expansion of a field of study and mapping of material within a transnational framework that allowed for research at the intersection of Asian and Asian American studies, but also a theoretical decentring of both fields. That is to say, that the concept of ‘Global Asias’ enabled Asian studies to embrace the epistemological tactics of Asian American studies to resituate the gaze of Asian studies and encouraged Asian American studies to embrace more multilingual and transnational scholarship to ‘challenge the US-centrism of concepts governing Asian diaspora.’3

Global Asias provides a starting point for thinking through new ways of imagining Asia from multiple, contradictory and entangled vantage points, for expanding how we envisage Asian diasporas beyond Asian American studies, and for understanding how Global Asias can function as a critical activating concept beyond geographies in order to articulate new theoretical positions and solidarities. This essay, in particular, probes how thinking and enacting Global Asias from/through London excavates questions of belonging in confrontation with Empire, galvanises affective communities and identities not captured by the nation-state, and builds solidarities beyond Global Asias.

The concept of ‘Global Asias’, with its vast scope that includes half of the world’s geographies and their diasporas through an interdisciplinary and transhistorical lens is, as Tina Chen points out, ‘critically imperative to imagine into being and necessarily impossible as a fully achievable field of academic inquiry.’4 That is to say, that its vastness exceeds the managed separations and partitions wrought by the cartographies of Empire and its epistemologies, but it is precisely because of its horizon of infinity that it is critical to visualise it as a horizon of imagination. Like Paul Gilroy’s Black Atlantic, the concept of ‘Global Asias’ is not essentialist, but conjured in order to envision new affiliations activated by relational histories in order to overcome the perennial problem of Global Asias — its invisibility.5

Global Asias provides a starting point for thinking through new ways of imagining Asia from multiple, contradictory and entangled vantage points ...

The field of study opened up by Global Asias calls for a shift from Asia as object of study to Asia as subject, as an agential force that both complicates narratives produced about Asia by surfacing its internal inequalities and difficult histories, and also seeks to make visible the historical, cultural, linguistic, religious, social, political and geopolitical threads that tie it together (albeit in attenuated pieces). In this respect, the concept builds upon Kuan-Hsing Chen’s Asia as Method and his call to decolonise, de-Cold War, and de-imperialise Asian studies by utilising Asian studies in Asia and what he calls ‘inter-Asia referencing’ as critical tools to address issues such as Japanese imperialism, and Muslim histories in Asia.6 By including diasporas (including to other non-Western regions) and self-consciously engaging with European imperial histories as sites of friction that produce histories and meaning, the concept of ‘Global Asias’ embraces the importance of interrogating the epistemes of Asian studies, yet refuses to locate any site of authentic criticality, preferring to world Asia from multiple vantage points. If, for Paul Gilroy, the ship was a key metaphor for imagining the Black Atlantic, what metaphors could be used to visualise Global Asias? Is there a poetic language generous enough to encompass Global Asias without being reductively identitarian, but which would capture its worldmaking capacities and its histories of being worlded from other places? Would it be useful to imagine tea, textiles, or something else as loose synecdoches for these vast territories, their diversity, their mobility, their significance as objects of desire and vectors of trade, cultural exchange and colonial appropriation? The history of tea provides a rich archive of potential histories to be unravelled. Its premodern transcultural histories enable an imagination of global encounter prior to European domination — from its origins in China in 350 CE to its circulation with Turkish and Mongolian traders by the end of the 5th century, its rise as marker of elite tastes and public socialities in the Tang Dynasty (618–907 CE) with the establishment of teahouses, and its dissemination from there to Japan, Tibet, Burma and Central Asia, each with its own distinct tea culture.

If, for Paul Gilroy, the ship was a key metaphor for imagining the Black Atlantic, what metaphors could be used to visualise Global Asias?

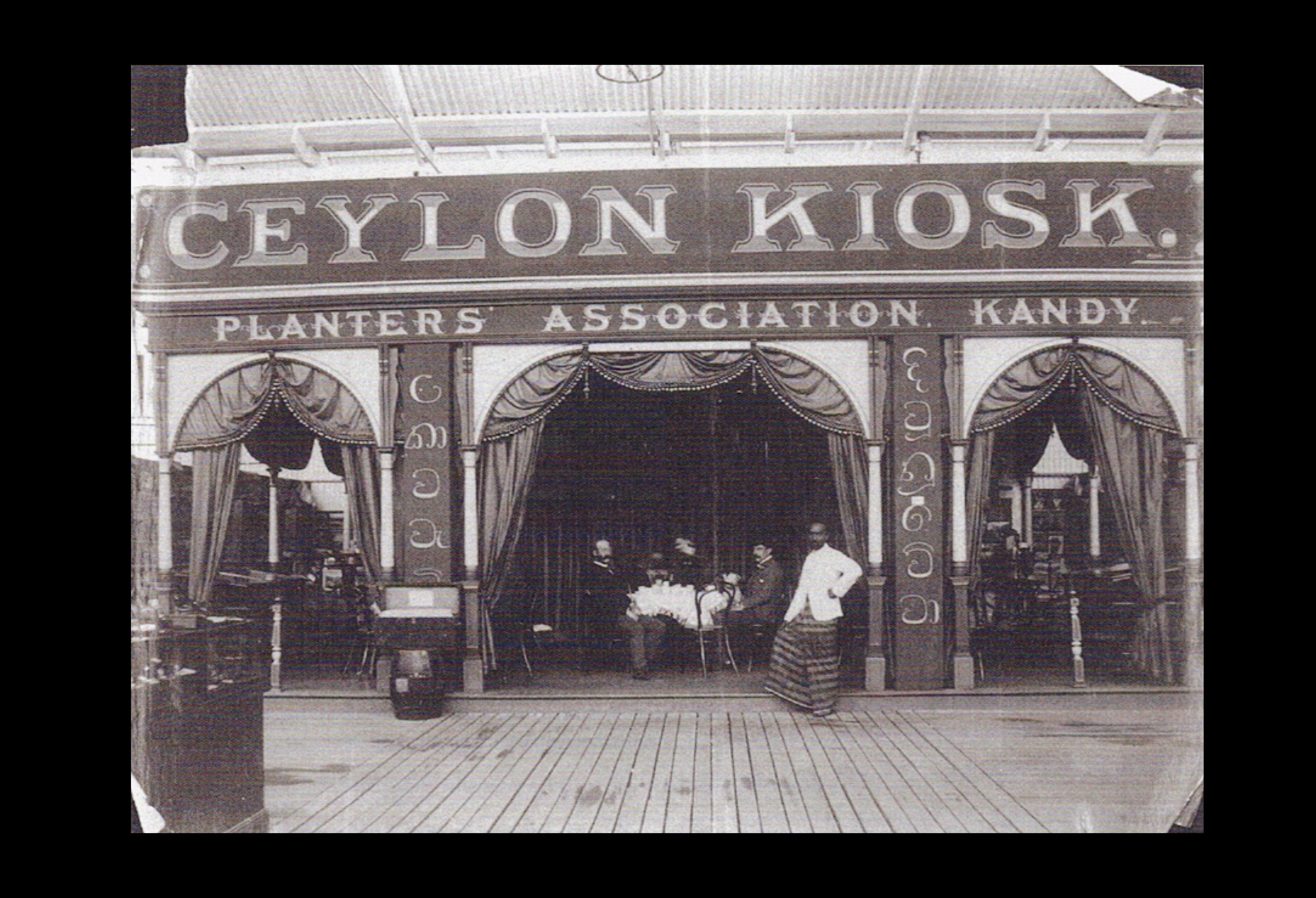

The Ceylon kiosk at the 1889 New Zealand and South Seas Exhibition, Dunedin, as reproduced in The Maui Dynasty catalogue, Suter Gallery, 2008

Hocken Library, Uare Taoka O Hakena (Neg. S04-060b)

Tea — along with silk and spices — was a key commodity that circulated along the Silk Roads, and that aroused the desires of European powers. The role that tea played in the rise of the Empire reveals the lengths to which the British went to secure this precious commodity. Indeed, the East India Company began trading opium in China in part to redress the trade imbalance caused by European desire for tea, which led to two Opium Wars (1839–1842; 1856–1860) and the British control of Hong Kong until 1997. It was in this context that the Scottish botanist Robert Fortune was commissioned to engage in corporate espionage in 1848, when the British faced the end of their 200-year monopoly on Chinese tea. His stolen botanical samples of Camellia sinensis were then transferred to the Indian Himalayas for cultivation with Indian indentured labour, where they established the foundations of a British-controlled tea trade. Their secret was not well guarded, however, and in 1899, the Persian diplomat Mohammad Mirza Kashef Al-Saltaneh brought 3000 tea tree saplings from India to Giran to satiate a West Asian taste for tea that had been growing since the Safavids (1501–1736). Nevertheless, tea and tea culture emerged as central to British national identity, obscuring its Asian origins yet retaining its metonymic ties to power and empire. As Stuart Hall wrote, ‘I am the sugar at the bottom of the English cup of tea … That is the outside history that is inside the history of the English. There is no English history without that other history.’7 For Global Asias, tea might then provide a loose historical framework that enables us to visualise its intertwined, colonial and diasporic histories, to critically interrogate modern ethno-nationalisms and imperial histories, and also to excavate the ways in which Asian histories and bodies have been made invisible.

✲

Global Asias and Asia-Art-Activism

To enact Global Asias from London, as Asia-Art-Activism does, provides a particular vantage point that resonates with other sites of diaspora, but also confronts Empire directly, thinking through colonial legacies in Asia, relational parallels and entanglements between them, as well as the complexity of Britain’s present. Additionally, by taking an activist position vis-à-vis Asia and building affective communities beyond national identities, AAA opens spaces for alternate identifications and political solidarities, unlocking Global Asias as a critical category that self-consciously reimagines discourses on race, and also brings new perspectives to gender, sexual identification, class, disability, environment, justice and their intersectionalities.

In so doing, Asia-Art-Activism brings Asian diaspora discourses back to their origins in the UK, back to solidarities with political Blackness, or perhaps the possibility of some other new concept that has yet to be defined. This nuance brings a new power to Global Asias as a critical concept by conceptualising Asia in relation with other formerly colonised territories. This is not to claim that all histories of colonisation are equal, nor that all parts of Asia were colonised, nor that there are not also histories of colonisation within Asia. By understanding these histories together, however, we are, as Shu-mei Shih argues, ‘bringing into relation terms that have traditionally been pushed apart from each other due to … the European exceptionalism that undergirds Eurocentrism’,8 and creating the possibility of larger patterns and solidarities to emerge.

In asserting Global Asias through art activism at this moment in history, when the ongoing and historical violence against Asians is only now just beginning to be seen, this act of imagination is crucial. It is through art, through discourse, that Global Asias can overcome its invisibility and be reimagined as a positionality, and through activism that that positionality evades essentialism, nationalism and ethnocentrism, maintaining its critical perspective that seeks justice above all.

✲

Asia-Art-Activism: Experiments in care and collective disobedience is a polyvocal collection of eighteen essays by leading academics, artists, curators and researchers who address urgent questions of the complexities of UK Black/Asian race relations and migrations, in parallel with global Black/Asian political entanglements and tensions, reflections on the rise of anti-Asian/migrant sentiment in the UK in relation to the ‘hostile environment’ and the weaponisation of the Covid-19 pandemic.

Across discursive and creative pieces, writers also explore where Asia is situated within institutional narratives of British art, the nature of transnational solidarity, and how ‘diaspora’ can work as a lens to inform and inflect cultural activities. It also includes artistic contributions from AAA Residency Associates from 2018–21.

Edited by Annie Jael Kwan and Joanna Wolfarth

Learn more about AAA and keep an eye out for additional printings of the book here